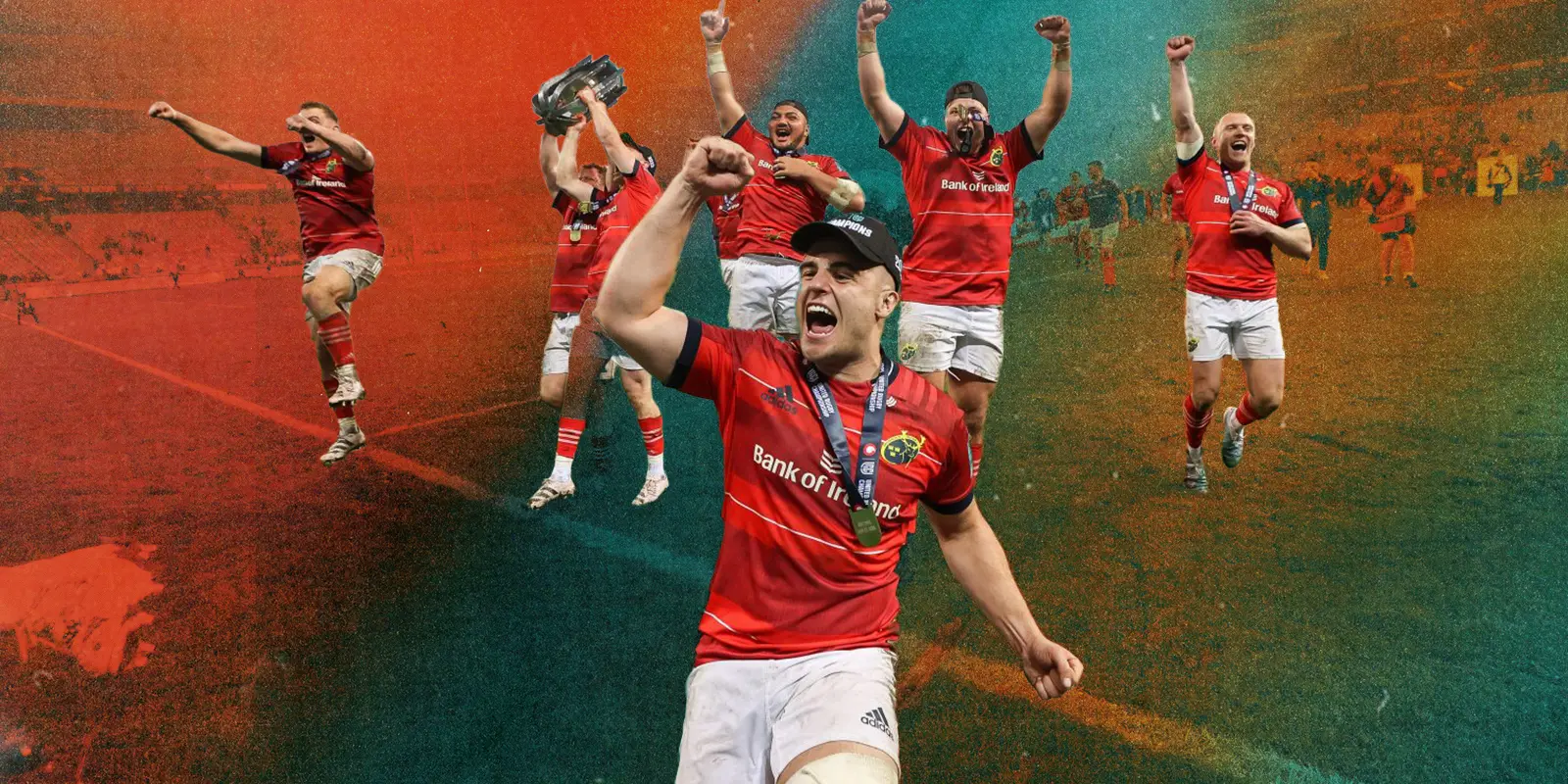

On the 27th of May, 2023, Munster beat the Stormers in Cape Town to win the URC title. I titled that ‘Wally Ratings’ as ‘The End of Heartbreak,’ and it truly was.

As finals go, it was everything you could want. Dramatic. Huge momentum swings. A late winner, even later drama. It felt, all at once, like the end of a journey and the beginning of one.

In my Anatomy of a Season article from that year, I wrote;

Where do we all go from here? Well, as of the first game of next season, we’re the champions of nothing. We’ll have an enhanced target on our back and a bunch of provincial rivals looking to put us back in the place they caged us into for more than a decade.

It’ll be up to us to take what worked here and build on it, relentlessly, until we’re lifting more trophies and winning more big games. It’ll be hard, but will it be harder than winning this trophy without playing a home game for two months, with every single knockout game played on the road?

No.

It won’t.

And if we remember that, we won’t go another 4382 days before we lift another trophy. They always say, winning a trophy gives you a taste for more. We will need to be voracious, and I think I can see that hunger building already.

The season after, we made the URC semi-finals before losing to Glasgow, who would go on to win the tournament, and exited the Round of 16 of Europe to Northampton, with half the team puking on the sidelines thanks to (another) badly timed virus jogging through the squad.

Last season, the season started abysmally, and Munster parted ways with Graham Rowntree at the end of a disastrous November. All of a sudden, the rebuild that looked like it started in 2022/23 had stalled out.

In truth, the damage had been done in the winter of 2022 and, to an extent, all the way back in December 2021.

I’ll get to that in a while.

Here’s how I like to work. I find out what I can at the moment, and write the truth as I see it. Sometimes, that truth changes later through external factors. I find out what the intent is, what the plan is, and then that plan has to engage with the reality on the ground, which happens later.

Immediately post-URC title win, the ground shifted underneath Munster.

Jean Kleyn’s re-declaration for the Springboks set a chain in motion that ultimately saw RG Snyman depart the province, something he didn’t want to do, and Munster didn’t want either. David Nucifora, the then Performance Director at the IRFU, decided that Munster couldn’t have two NIQs in the second row, so he forced Munster to choose.

At around the same time, in October 2023, just after the 2023 World Cup, he decided that future Ireland captain Peter O’Mahony, and Conor Murray — both of whom played heavily for Ireland over the next two seasons — would have to be paid 50/50 or 60/40 from Munster’s provincial budget, after being on full central contracts to that point, something that was not expected for other heavily used core internationals at that point.

Immediately, Munster’s intent to keep Snyman alongside Kleyn and invest in the front row and other slots was thrown into disarray.

Over the previous two seasons, all of the provinces had their budgets cut post-pandemic. Leinster were in the same boat but, at the same time, saw the number of 100% IRFU central contracts explode to include players like Doris, Van Der Flier, Sheehan and others, so their budget cuts were offset, while the other provinces saw their 100% central contracts reduced to almost nothing at all. Again, you know this.

What that meant in practice was that Munster had to do more with less.

***

When Van Graan announced that he was going to leave Munster at the end of the 2021/22 season in early December 2021, the province was thrown into a blender. Van Graan, who had signed a two-year extension to take him from 2022/23 to 2023/24 as head coach back in April 2021, took up a big-money offer in Bath, triggering his six-month exit clause.

The reasons for that have been fairly well documented on these pages — a feeling that he’d grown stale at the province, struggles to improve the squad within the budget frameworks that had been squeezed on him in the previous two seasons, and some frustrations with the model that had brought Snyman and De Allende to the club two seasons before.

When he left, it set off a chain of events that would ultimately lead to the promotion of Graham Rowntree to the head coach position, with Mike Prendergast and Denis Leamy coming in as assistants, and Andi Kyriacou getting a promotion from the academy pathway to the senior squad.

Around the time of the hiring process — which only really kicked into gear properly in mid January once the IRFU Performance Director returned from Australia — it became clear that there would be some difficulty in appointing an experienced head coach to the role.

Graham Rowntree was not the first choice, but became the only choice that made sense to Munster, first, then the IRFU, as the process dragged on for months.

When you’re signing a head coach, especially one employed elsewhere, you ideally want to start looking as early as possible in a seasonal cycle. So, essentially, around October/November of the previous season, if you’re looking at Super Rugby, or the previous March if you’re looking in Europe for the following July. When you go looking in January, you’re going to be picking from guys who are either on the outs with their current club, working in Japan or, depending on contractual cycles, someone from Super Rugby, which is incredibly difficult as they are usually in the middle of a Super Rugby pre-season at that point.

The second thing you’ve got to sell is the project itself. When you’re signing a big name or a coach with a good reputation, you have to know that you’re going to have to entice them, first with competitive wages and a package for their family to move, but also with a level of freedom to shape the squad as they see fit.

No coach who has options is going to rock up at a club knowing that they are going to bump into the same issues that saw the previous head coach decide he was better off elsewhere.

Speaking to one of the coaches the IRFU spoke to in the last few years, when they did their due diligence on the squad and asked about the scope to upgrade the front row/front five, they were told that it would not be possible in the short and medium term, something that Van Graan was also told in the Autumn of 2021. That was a deal breaker. Any coach who is looking to move to Munster is immediately aware of the expectations, regardless of where the squad is at; compete for domestic and European trophies, or the pressure will build. If you know the team needs X to be successful, and you’re told X is not possible, but you could try Y, you’re going to immediately realise that you can’t be successful.

Rowntree, who believed stepping up to head coach would be an excellent step for his career, made a pitch mostly settled around improving what was already in the province and leaning on youth. As different coaching targets dropped out, he became the option that made the most sense for Munster first, who needed some level of coaching clarity at that point, and eventually the IRFU relented and made the hire.

At that point, we’d already signed one of Van Graan’s targets for the following season — Malakai Fekitoa — but missed out on three targets from Leinster, namely Dan Sheehan, Ciaran Frawley, and Will Connors.

We’d later sign Antoine Frisch later in the season, but the problems in the squad remained.

When I tell you that nobody in the IRFU system expected to end the following season with a trophy, believe that. It was completely unexpected and both a vindication of the hiring of Rowntree — and his approach — and a handbrake on future development.

Here’s some Inside Baseball for you; when dealing with David Nucifora on signings, you’d often be told that signing an NIQ wasn’t needed because, sure look, don’t ye have [guys currently in the squad] who, supposedly, are close to getting recognition at Ireland level, and this was especially true after that season’s newly reformed Emerging Ireland squads. The focus at that point — and it still is, to an extent — is that the provinces were there to produce players for the national team, and that the Emerging Ireland tour, however hastily rearranged or haphazard in timing, was the IRFU getting something back from the provinces. So why would you sign a hooker when you already have hookers who are in that frame? Or a prop? Or a lock?

After the URC title win, Munster’s focus naturally went to improving the squad to kick onto the next level. We’d just won a URC title, so how could we move up to start competing in Europe? The areas to do that were clear — front row, more power and pop in the back five.

That summer, the IRFU partnered up with Munster to bring Oli Jager to the club in November 2023. Jager was a long-term target for the IRFU, and once he missed his window with the All Blacks due to injury, they really wanted him in Munster. Leinster also made an offer around the same time, but the IRFU wanted to get Jager into Munster to have an IQ option at tighthead, and he’d make his test debut in the Six Nations that season. That, combined with the return of John Ryan from the Chiefs after a period at the Chiefs and a joker period back at Munster post-Wasps collapse, was seen to be enough for that NIQ question to be answered.

We had plans to upscale our options at hooker with Johan Grobbellar, but the shifting finances around Murray and O’Mahony, who Munster expected — rightly — to remain on full central deals until the end of their careers, given their importance to the national side, meant that the financial picture changed relatively late in the season.

But, at that point, with Snyman leaving the province, we wanted to use some of the funds to free up moves for other areas like loosehead and the back five, especially when we’d replaced Fekitoa with Alex Nankivell. With Murray and O’Mahony now on split PONI deals — and both men were incredibly well paid — our wiggle room for a big forward signing disappeared in a few weeks, especially with O’Mahony telling the province that he’d only make his decision on his future after Six Nations 2024. It dragged on and became incredibly messy politically and perceptionally.

We made a few moves in the IQ market — Leinster, essentially — but they came to nothing, mostly due to the inertia of the player wanting to stay where they were, especially when the pitch was “move here to help your Ireland chances”, which was simply not a realistic thing to include in a pitch at that point.

Avenues for getting a NIQ back five players — to improve our power profile in the aggregate — were similarly shut down, in part because of dispensation, and because our funding had been eaten up. We ultimately decided to pivot to a strategy that would see us go for pace on the edges to compensate for our growing issues in the pack, especially with Zebo’s retirement and Carbery leaving the club. We signed Kilgallen and Abrahams for the following season, but lost Antoine Frisch to Toulon after a prolonged departure once it became clear that test rugby in Ireland was not an option. We had been looking at Tom Farrell as a guy to play with Frisch and Nankivell, but in the end, it looked like trading Frisch for Farrell. Farrell would go on to be a big success in his first season, but we were now weak in midfield, meaning another body would be needed there eventually.

At that point, the areas where we were lacking top-end quality — hooker, loosehead, second row — were pretty clear, and also heavily exacerbated by apocalyptic injury crises, including the ongoing injury to Roman Salanoa, who was in the Ireland frame before his now three-season-long recovery from what was, at the time, a relatively routine knee injury. The same could be said for Edwin Edogbo.

These issues all came to a head in 2024/25, as coaching issues, injury issues and quality issues saw the club start the season as badly as it’s possible to do. For a while — up until late in the season — it looked like we’d miss out on the Champions Cup pool stages for this season, which would have been disastrous financially. We pulled it out of the fire, and the season was somewhat saved by a win in La Rochelle and a decent performance in defeat away to eventual champions UBB.

At this point, we were still heavily reliant on a lot of the front five players we knew in 2023 would need to be replaced or improved on so they could cycle down the depth chart.

Injuries to Oli Jager meant John Ryan and Stephen Archer had to play most of the season as rotating starters, and we’d sign in guys like Dian Blueler short-term, before making a move for Michael Milne and Lee Barron in the front row for this season, and they both joined the province on loan at the end of 2024/25 because we had (a) a bunch of injuries at loosehead and hooker, and (b) the IRFU realised we needed a bump in quality to get us into the Champions Cup to empower Clayton McMillan, who had been announced earlier in the season and who would take charge in July.

At this point, David Humphries and the Munster hierarchy were very clear on the scale of the rebuild that would now be needed after varying issues changed the picture in the previous two seasons.

Not only that, I think it was clear that some of the prospects we’d leaned on post 2021/22 hadn’t quite developed to the level we wanted them, mostly through injury, but not entirely.

We knew we had some guys who were ready to take the next step with any kind of run of fitness — Ahern, Edogbo, even Gleeson, who missed a lot of 2024/25 with a shoulder injury — and talented role players who were in and around the Irish conversation at that point like Coombes, Milne, Jager, Loughman, Farrell and Nash. Beirne, Crowley and Casey were firmly in that top-level conversation, but outside of those guys, there were a lot of players who would clearly do well with quality around them, but wouldn’t drive that top-end quality on their own.

Kleyn, Nankivell and Abrahams were our NIQs at that point, and still are this season. Nankivell has been the most consistently effective when fit — and may eventually become IQ — but Kleyn and Abrahams have had spotty injury records in the last two seasons, and clear systemic drawbacks that come with their undoubted qualities.

***

That brings us to this season, where we’ve seen a lot of good and a lot of bad in the squad.

Levels have fluctuated block to block.

I think it’s fair to say that, outside of Croke Park, we haven’t seen the usual world-class quality from Tadhg Beirne, and while he seems to be suffering from something of a post-Lions hangover, we also have to recognise that he’s 34 years old — the same age as Iain Henderson in Ulster with more than double the minutes over the last three seasons — and far closer to retirement than anyone realises.

When McMillan came in this summer, he knew immediately that he would need reinforcements at tighthead, and that was approved by the IRFU even before Oli Jager’s recurring concussion issues. In that regard, Ala’alatoa is a stop-gap solution until the end of the season, where it’s expected Munster will finally be allowed to make some of the signings that have been required in the front five for years, along with other areas in the squad.

But it doesn’t end there.

In reality, the squad overhaul will take two cycles to fully fix. The talent is there in the academy — back five, halfback and back three in particular — but it is acknowledged at all levels that they will need support, especially as a few good front row prospects develop in the next season or two.

It is now widely acknowledged at an IRFU level that our young talent and even established, core guys like Casey and Crowley, in particular, can only do so much if the levels in the pack, in particular, are not consistently high enough.

A lot of that reflects the context of the last four years. In the face of progressive budget cuts and massive injury lists for the guts of three full seasons, Munster have been conservative when it comes to squad rebuilds, which are generated by players coming in, but also players going out. If Munster were an English club, for example, it would be relatively straightforward. You have your yearly budget, you know what you’re paying now, and what would be freed up if you cut X from the playing budget, on top of any extra money you might get in from private funding. You wouldn’t necessarily have to focus on purely home-nation-qualified players, so you could go big on the areas you need to bolster immediately, while also knowing what your prospects are in your academy system.

In a simplified way, you know you’ve got a top-level tighthead prospect aged 20, but he won’t be ready for the usage you need until he’s 22, so you sign a guy on a two-year deal to get him there and, if he works out, great, if not, you give him more time and keep the guy you have or replace him.

In the Irish system, it’s more complex. While there has been a rethink in how NIQs are used, the ultimate aim is that the four provinces must produce players for the Irish national team. The men’s national team funds almost everything else in the system, so that takes priority.

In the Irish system post-pandemic, and arguably for most of the 2010s and early 2020s during Nucifora’s time, that wasn’t possible. The best example of winning rugby teams comes from the quality of their front five, and the Irish national team is no different. Nucifora’s idea was that if the four provinces all have mostly Irish-qualified front fives, then the quality will naturally be produced via game-time and top-level exposure. It was this concept that saw Stephen Moore stalled out until a no from the player was inevitable around 2016, and why Van Graan was repeatedly turned down for a tighthead prop in the late 2010s, early 2020s. The logic was that if you sign an NIQ there, it’ll reduce the game time for guys like Niall Scannell, Dave Kilcoyne or John Ryan, who were in the test frame at that point. This logic was mostly replicated across the four provinces, with Connacht being something of an exception at times.

In practice, that produced a system where you were better off having no prospects or fringe internationals at all, if the alternative was that you had to stick with players who were in the test depth chart, but not reliably used, so you couldn’t upscale that particular unit for reasons that didn’t fully make sense as far as your province getting better were concerned. You got the worst of both worlds in that scenario. Ulster signed Toomaga-Allen and Steven Kitshoff partly on the principle that they had no prospects in the building that were anywhere close to test level at that point, or when they had young players with injuries at key points.

A practical workaround at the time was the project player market. In 2016/17, Munster were supposedly interested in using Wilco Louw as a project player, before Rassie capped him almost immediately following his move back to the Springboks. Munster solved a problem in the second row with Jean Kleyn in 2016, as did Leinster in their problem spots with the signings of James Lowe and Jamison Gibson-Park around the same period.

With the project player market mostly closed — you have a five-year project player rule in place now, as well as the possibility of allegiance switching — it’s mostly accepted at an IRFU level that if a player isn’t looking like they’re going to be a test-level player in a core area, no amount of game time will change that.

This, along with the concept that if the provinces are doing well, the IRFU will benefit up the chain, as opposed to the previous thinking in reverse — trickle down economics in rugby form — will mean that the old way of looking at NIQs “blocking” players is on the way out.

In the previous four seasons, Munster knew they had core areas that needed to be bolstered from outside, but couldn’t do so for the reasons I’ve outlined, and that lead to “stasis” retention, where the player you had in the squad, regardless of weaknesses, was a better punt than relying on academy players you knew weren’t ready, or IQ players from outside who historically have had way more misses than hits.

That will be the core of the rebuild that will happen now.

That means more options for McMillan, who took the job empowered by the knowledge that he could have as free a hand as the system allows, on top of the development of the young talent we know we have in the building already, and who soon will be.

It will take time, but the right people are in the right spots with the freedom they need. With that time, they’ll get there.