What can you say after that?

A team we should have beaten. A team that all the metrics during the game say we would have beaten. But somehow, we find a way to lose all the same. It’s become a hallmark of this group of players over the last few seasons, and old habits die hard when the pressure comes on.

How else do you explain an opening eleven minutes where we conceded ten points? I spoke in the Blood & Thunder podcast about how, if we went down on the scoreboard early, that this game could get incredibly messy, and that’s exactly what happened. Instead of making Castres check out, we gave them all the encouragement they could want that we were fragile, mentally weak and there for the taking.

A lazy offside penalty. A missed tackle off a maul. Ten points down, and revealing ourselves, once again, to be our own worst enemy.

Worse than that, though, it feels like we’re the only side that turns up to Thomond Park and plays down to the occasion. At the end of the match, the Castres players and their supporters were jumping around with each other in ecstasy while we ambled to the sideline, waiting to clap them off, with the fans streaming out of the stadium.

Just like the Stormers. Just like Leinster.

The crowd, by the way, were superb throughout. Twenty thousand odd people in the stands, loud for the entire game and roaring encouragement from one to eighty, even when the game looked dead and buried with five minutes to go.

They showed up ready to win. Too many players did not.

***

We won the ball, won the line breaks, won the entry count, won the carry/pass volume… and still lost because Castres won the two things that actually decide tight games: 22m efficiency and points off the tee (plus a cleaner turnover profile).

Five tries shouldn’t lose you the game — unless you leak the full value value

- Munster: 5 tries, 2 conversions, 0 pens = 29

- Castres: 4 tries, 4 conversions, 1 pen = 31

That’s the match right there:

- We scored one more try, but Castres scored +7 from goal-kicking (8 vs 4 from conversions, plus their penalty).

- We left 3 conversions = 6 points on the table. Even one more makes it a draw; two more wins it.

This wasn’t only goal-kicking, but it’s the clearest explanation for how a “more tries” day becomes a loss.

Red zone efficiency: we lived in their 22, they cashed theirs

22m entries

- Munster: 12 entries, 2.4 points/entry

- Castres: 7 entries, 4.0 points/entry

So we had +5 entries and still lost because:

- Castres were basically scoring a try (or nearly a try) every time they got into our 22.

- We were busy rather than clinical: lots of possession, plenty of visits, not enough “entry → immediate scoreboard”.

Castres needed 7 entries to get 31 points. We needed 12 entries to get 29.

That’s an efficiency gap you don’t outwork.

Volume vs value

Attack volume

- Passes: 256 vs 107

- Carries: 155 vs 89

- Rucks won: 98 vs 69

- Line breaks: 14 vs 7

This is the classic profile of: we controlled possession and created moments, but we either:

- didn’t convert breaks into clean finishes, or

- got dragged into phase bloat and coughed up the ball/tempo before the kill shot.

That’s reinforced by the turnover and set-piece leakage below.

The tactical fork in the road

Kicking + game management

- Total kicks: 30 vs 37

- Kick-to-pass ratio: 1:8.5 vs 1:2.9

Castres played a far more “Top 14 away win” style: more kicking relative to passing, prioritising territory, contest, and pressure.

We, by contrast, were hyper ball-in-hand. That can work, but only if you’re ruthlessly efficient in the 22 and squeaky-clean at breakdown and set piece. We weren’t.

Two hidden killers: lineout leakage + turnover balance

Set piece

- Lineouts: 17 at 76% (that’s ~4 lost)

- Restarts received: 6 at 83% (1 lost)

- Scrums: both 100%, but Castres had double the scrum count (6 vs 3)

In a two-point game, losing 4 lineouts + a restart is enormous. Those are free possessions — often in good field position — and they’re exactly the kind of moments Castres turn into entries.

Turnovers

- Turnovers won: 5 vs 7

- Turnovers lost: 15 vs 12

So we were -3 on turnover count and, more importantly, we had 15 possessions end in a mistake. With the amount of ball we had, that’s the definition of inefficiency.

Ruck speed

- 0–3s: 48% vs 47%

- 3–6s: 40% vs 29%

- 6+s: 12% vs 24%

Our ruck ball wasn’t disastrous (nearly half was 0–3s), but the broader profile says:

- We had a high ruck count (98) and high phase load,

- Castres were happier to defend long sets, slow their ball when needed, and wait for the swing moments (turnovers, exits, set piece, goal-kicking).

Why Castres led for 54 minutes

Time in lead:

- Munster: 12 mins

- Castres: 54 mins

Even with 67% possession in the last 10, we could only match the final surge 7–7. That’s the story of a team chasing: you can have the ball at the end, but if the opponent’s efficiency is higher, you’re always trying to climb a ladder they keep pulling out from under you.

Bottom line

- We weren’t clinical enough in the 22 (2.4 points/entry vs 4.0).

- We lost the goal-kicking battle badly (and that’s fatal in a 2-point game).

- We leaked “free possessions” (lineout + restart losses) and had too many unforced turnover endings.

- Our low-kick, high-phase approach gave Castres exactly what they’re built for: defend, absorb, and punish turnovers, which they did repeatedly.

There are no positives to take from this, other than the performances of Casey, Edogbo, Loughman, Wycherley, Daly and, to an extent, Abrahams. Crowley was good during phase play, but his kicking off the tee was unacceptable at this level, even allowing for the difficulty of the kicks, because so many of our tries squeeze into the far corner, another constant of the last few seasons.

I can’t shake the idea that this game was, essentially, our win over Cardiff earlier in the season, but inverted. A narrow home win against a team that seems to convert every entry into a try, into a narrow loss against a team that seems to convert every entry into a try.

We are a good defensive team, for the most part. We don’t concede easy linebreaks except for in two areas: post-turnover and off penalty ladders up the field, where we concede two penalties in a row.

The turnover part is more meaningful because I can’t really explain why Jack O’Donoghue gave away this penalty, or why Tom Farrell did either of these. The neck roll at the ruck, when we were 22-17 up, was insane. The intercept, less so.

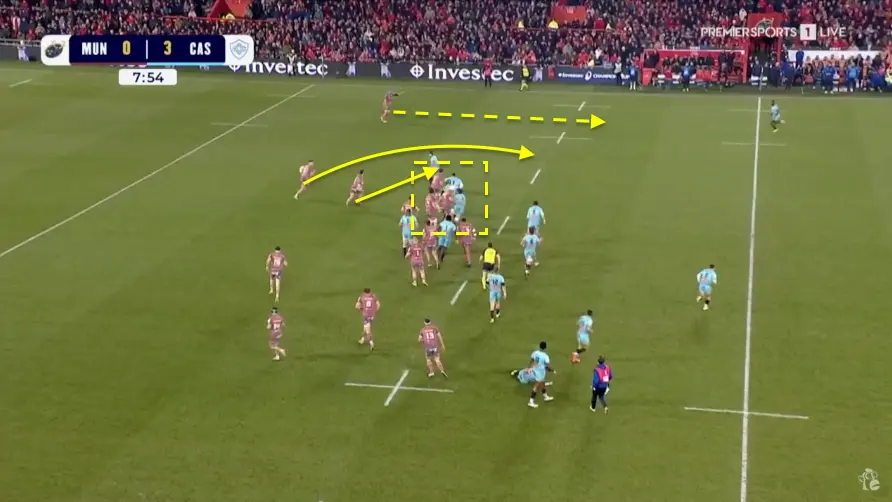

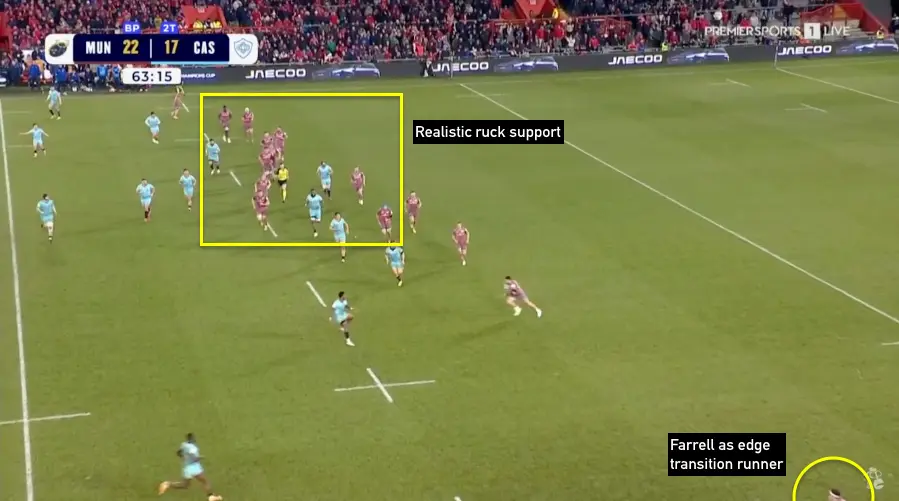

Here’s the build-up to the Farrell penalty for the deliberate knock-on, though. And it’s good, right up until it’s not. We take a contestable from Castres, and go straight for a transition kill shot across the field in a full 3-3 central shape.

The shape in the middle works as intended.

The middle line of three blocks off the central line of Castres’ defence, with O’Donoghue blocking off the second last defender from transiting across, leaving Nankivell, O’Connor and Beirne to attack an isolation on Cope, with Ambadiang stepping up from the secondary to cover.

For me, O’Connor just had to keep running here. He passes to Beirne, which isn’t a bad idea in isolation, but Beirne is decisively slower than O’Connor, so it actually bails out Castres broken defence in that moment.

That gives Vanverberghe a chance to recover here to press the resulting ruck, rather than being involved on a potential stretch tackle on O’Connor.

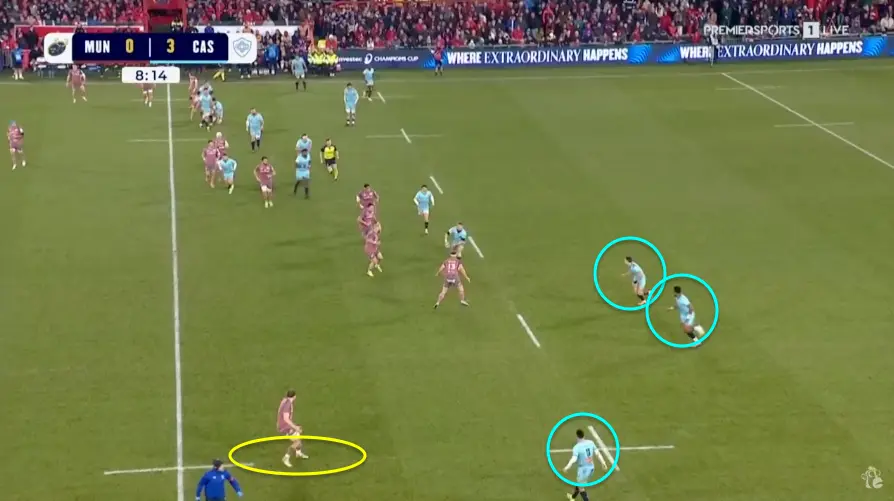

The ball squirts out of the ruck under pressure, Casey has to scramble, and Castres are free to attack on turnover. One phase later, we’re left with this picture. Farrell is guarding the edge — and he can’t scramble on the pass here, so he gambles on an intercept — because Coombes, who had filed out to the edge to be a heavy edge finisher on the next phase, was now guarding 20m of open space against three attackers.

If this goes to hand for Castres, it’s a certain try.

Left with three bad decisions — Farrell gets scorched on the edge because he can’t cover laterally, or Coombes gets scorched on the edge by any one of three players, or concede a penalty for a deliberate knock-on (that might end up being an intercept) — Farrell picked the least worst one with the only upside.

On the next sequence, we’d concede to Karawalevu anyway, when he’d run an inside line straight through Coombes on the pillar, who flapped at an arm tackle against the grain and got blown straight through for 0-10 Castres.

All produced from an attacking sequence that got blown because of one decision — a young winger passes instead of running through. Should everything be that low margin, though?

It feels like we stretch the play so much — and our attacking line in turn — that any turnover of possession forces a radical compression of the transition defensive line to react, leaving huge edge space to compensate.

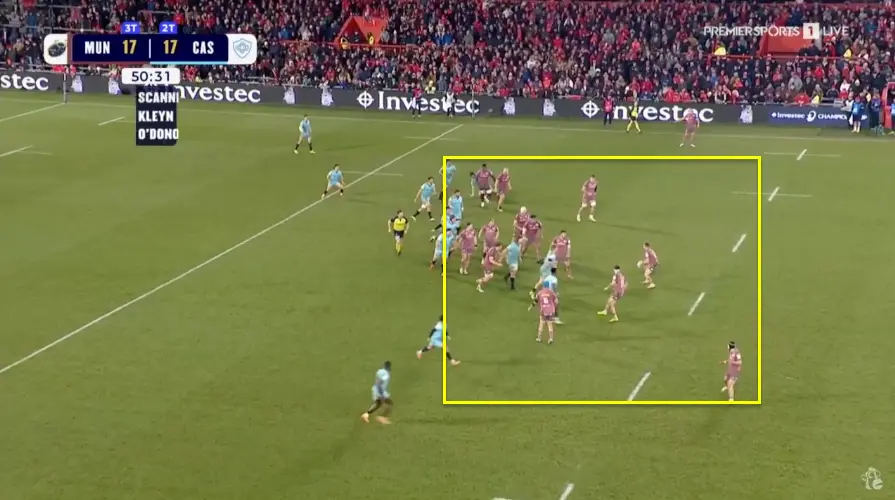

Here’s another example, albeit an inverse. The try was ultimately disallowed for that forward pass you see, but look at how compressed we are when the ball comes back across.

There are 14 Munster players in this square, 30m of lateral space.

However, to understand why this happens, we must examine the previous phase.

Farrell carries off the lineout, we send three players into the ruck. When it comes back, the call comes to hit the openside, but we only have Barron — who runs a dud line that neither acts as a carry threat or a blocker run — and Coombes pops a pass to no one.

What’s the play here? There is nothing a screen ball will achieve. Abrahams can’t secure a ruck against two forwards. Lee Barron is dead on the play, so can’t do anything with it. If the ball goes to hand, Crowley is running into two defenders, with no ruck support.

Was the play designed to have Crowley cut back against the grain?

I don’t think so.

We have no width back in the other direction, so he tries a kick over the top, that Castres recovered.

That previous play compressed everyone into that 30m of space, so when we lost the ball, the danger zone was obvious.

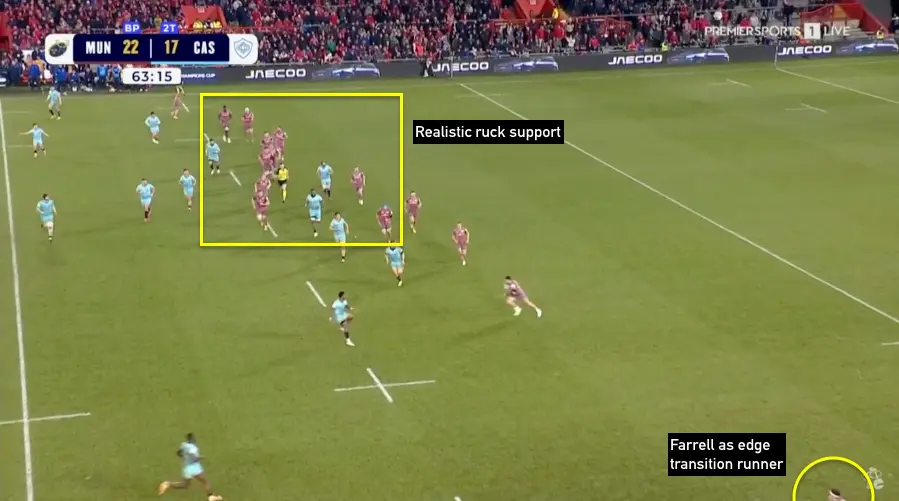

Even then, with just over fifteen minutes to play, a win in the bag plus a bonus point try, yet we kept putting the foot to the floor.

Castres had a penalty and missed touch, but instead of kicking it back, we ran it.

Do we need to run this gift back?

I get that we wanted to go two scores up — it kills the game — but we’re running ourselves into trouble here. Casey didn’t kick because he had no wing support, as Abrahams, who should have kicked, ran into contact.

Hanrahan couldn’t kick because Castres blitzed on him. Crowley probably should have kicked, but hit Kelly. From there, it was either a linebreak and a try or a highly contested edge ruck where we had a numerical disadvantage.

Farrell concedes the penalty, we go down to 14, Castres kick to the 5m line, and they’re back in the lead.

Abrahams should have kicked in the first instance. Crowley should have, but was worried that Ambadiang or Karawalevu would recover it and scorch our heavily exposed transition openside.

That left Kelly with a very difficult chance to convert, and it led to losing from a winning position.

We keep playing ourselves into low percentage chances that will provide either a huge linebreak or a panicked ruck, and very little in between.

All duck or no dinner. Too often, as of late, there’s been no dinner. We play too wide for the forward line we have, and lack the pace across the back three to consistently offer loop threats. Too much of our play ends up wiring ball to Tom Farrell in the hope he can produce an offload or a short ball moment that breaks open a defence. He doesn’t really create chances with space around him, so everything is dependent on high-speed, low-percentage short passes hitting their mark under pressure. Defensively, he can’t cover the same ground, so it feels like any turnover automatically takes four players out of the transition phase that comes after.

We look like a team that needs a small forward, but can’t afford that drop in tight physicality in our central pods, or with the lack of lineout punch that comes with it, but the players we select to shore up the lineout have drawbacks of their own that often means we don’t get the aerial dominance we selected for. Tom Ahern has been badly missed because he answers both of those questions — he’s a real threat on the edges and a dominant lineout forward — and without him, we get smaller and easier to contest out of the game.

Then, when we do run through the phases, too many of our centre-line players don’t punch enough holes, or look for a screen pass too often to compensate for the lack of punch, something opposition defences are well aware of at this point. If almost everything is a screen ball, and our attacking lines are flat by default, then all that produces is isolated runners with 60m of space behind them and no insurance.

There are deep systemic contradictions in our current setup that don’t appear on the road, because we lean into our strengths right now — kicking, chasing and playing on transition ourselves. At home, we want to push the tempo, but almost like a car with a broken gearbox, we can’t hit what we want to do without scary crunching sounds and the engine dropping off because we can’t keep up with the motion.

The harder we attack, the more vulnerable we look.

The more pragmatically we play, the more chances come to us, but we don’t quite trust ourselves to do that at home. The skills are there. Our consistency is not, and in the act of chasing that high-skill, high-tax, low-margin-for-error game, we leave ourselves exposed again and again.

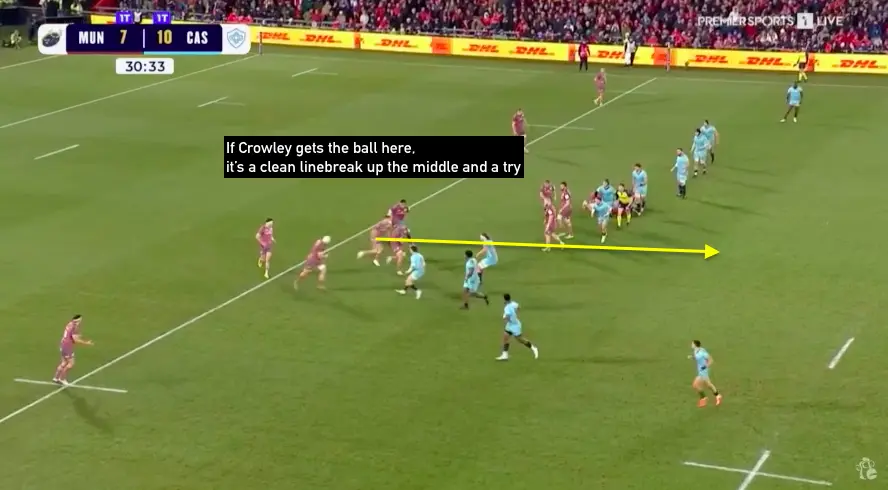

We have a great running #10 whose confidence off the tee is shot. We then can’t lean into what he’s really good at — and did well here — because we either don’t see the opportunities our approach produces, like here.

Crowley ran a line, called for the pass but didn’t get it.

Or we don’t provide enough punch in front of him, or creative speed on the loop behind him, to unlock the defences that blitz on us repeatedly.

He has to make his kicks — it’s a massive problem now — but if we have this approach, we must be able to execute what it produces, or we’re just going through the motions.

Then you look at guys like Coombes, Kleyn, O’Donoghue, Ala’alatoa, and others in the starting pack trudging into contact with no pop, no physicality, and wonder what it is we’re trying to do at all.

Not big enough to play direct against any team with size, not quite poisonous enough on transition to kill those same teams who want to kick to us and defend narrow, so we go through high phase counts to press and stretch them, but look incredibly vulnerable to passing errors and killer turnovers that leave us exposed when we do. In an attempt to outrun our squad’s weaknesses, we too often expose them.

A catch-22. It’s plain to see that we need more size in the front row and punch in the second row to empower our primary approach, with more sting and pace at fullback and on both wings than we currently have available. That fixes our gearbox.

With those weaknesses, we play phases for nothing. Ambition for nothing.

That turned a game where we scored 29 points at home — enough to win any game we’ve played this season, and all but two in 2025 — into a loss. We swung for the fences and clocked ourselves in the jaw.

And now we’re in the Challenge Cup.

| Players | Rating |

|---|---|

| 1. Jeremy Loughman | ★★★ |

| 2. Niall Scannell | ★★★ |

| 3. Michael Ala'alatoa | ★★ |

| 4. Jean Kleyn | ★★ |

| 5. Fineen Wycherley | ★★★ |

| 6. Tadhg Beirne | ★★ |

| 7. Jack O'Donoghue | ★★ |

| 8. Gavin Coombes | ★★ |

| 9. Craig Casey | ★★★★★ |

| 10. Jack Crowley | ★★ |

| 11. Ben O'Connor | ★★★ |

| 12. Alex Nankivell | ★★ |

| 13. Tom Farrell | ★ |

| 14. Thaakir Abrahams | ★★★ |

| 15. Shane Daly | ★★★ |

| 16. Lee Barron | ★★ |

| 17. Michael Milne | ★★★ |

| 18. Oli Jager | ★★★ |

| 19. Edwin Edogbo | ★★★★ |

| 20. Brian Gleeson | ★★★ |

| 21. Ethan Coughlan | DNP |

| 22. JJ Hanrahan | ★★★ |

| 23. Dan Kelly | ★★★ |