When Ireland lose a game, there’s always something of an inquest to find the silver bullet in the Irish media.

Was it the #10?

Has anyone drilled down on the #10 yet?

Is there some esoteric, nebulous malaise affecting the team that can’t be named?

Have we considered the #10???

The reality is that it’s rarely one player, one unit, or one element of set-piece battle to blame, but with that said, in 2025, any team playing behind a lineout that runs at under 80% is in big trouble. Any team running below 70% will find it almost impossible to beat an elite opponent.

On Saturday night, Ireland’s lineout ran at 69% on 16 lineouts, which is bad by any objective measure, but the reasons for this can often be incredibly complex. It’s rarely just the hooker, or the call, or the lifts, or the weather or even the lineout coach — it’s often a combination of all of these, intersecting with the pressure applied by the opposition, or not applied as it often goes.

No lineout ever happens in a vacuum.

First, let’s examine our lineout numbers from the 2024 summer tour to the present against elite international sides (top 10). If there is a problem, it’ll show up there.

Including Saturday’s game against the All Blacks, the following trends emerge.

- Baseline: Across the 10 games in my data set, Ireland average ~85% on ~15 throws/game (median 88%). When we include Saturday’s 69%, the rolling average dips to ~83%. An elite international lineout runs at 90% or above, so we’re a little below that, but not drastically when we look at the big, big picture. However.

- Southern-hemisphere squeeze: Versus SA + NZ the last four meetings, our lineout has run at 89%, 71%, 70%, 69% → avg ~75%. That’s a clear step down from the rest of the set (others average ~88%). South Africa and New Zealand seem to have decided that heavily contesting Ireland’s lineout — and committing the resources to doing that — is a winning play.

- Six Nations picture: Italy 100%, Wales 87%, France 95%, Scotland 60%, England 100% → avg ~88% but with a big outlier at Scotland (60%). So the ceiling is high, and volatility shows up against teams that contest heavily.

- Volume vs accuracy: When Ireland hit ≥15 lineouts, we average ~90%; when kept to <15, we drop to ~76%. Saturday (16 @ 69%) is the exception that proves the rule: NZ disrupted even with volume.

- Distribution of outcomes: From these 10 games, Ireland were ≥95% three times (Eng, Ita, Fra), 80–89% four times (Wal, Aus, Arg, SA1) and <80% three times (Sco, SA2, NZ prev) — now four with Saturday’s 69% v NZ.

Ireland’s lineout holds up — excels, even — against most top-10 sides, but accuracy and stability drop markedly against elite contesting units (SA/NZ, and Scotland on the day). When opponents restrict variety or dial up the contest, Ireland’s error rate climbs; when Ireland control tempo and volume, returns trend into the high-80s/low-90s.

This opens up the discussion around how your lineout often relies on the opposition’s defensive approach. Some sides simply don’t want to exert the resources required to counter-launch at the kind of volume that disrupts a lineout over 13/14 lineouts. Think about it — you have to move lifters across the ground, jumpers have to get into the air an extra 8/9 times before you even consider the jumping done on their own lineout. Anything you spend on that lineout approach can lead to drop-offs elsewhere.

Many teams — England and France, as an example — decide to “concede” the throw in most cases to commit to better maul defence or to ensure that they can break from the lineout at the same time the attacking team does, because, as you know, when you commit to a counter-launch, you take at least two, but usually three potential defenders out of the next two phases.

Ultimately, if your opponent is committing to counter-launch, you’re going to have a difficult time of it at the lineout. That is a fact.

New Zealand competed in the air or counter-launched on every single one of Ireland’s lineouts taken outside the 22.

Every. Single. One.

Immediately, that puts immense pressure on your calling structure, your lineout callers and the menu of lineouts you came into the game with.

When it comes to lineout calling and our menu in general, we have had some issues.

Back in November 2024, after beating Australia, Joe McCarthy told the media.

Before any game, the lineout coach will go through the menu of calls for the upcoming opponent during the week so the pack has a clear focus during the week. You might have multiple lineout calls in your book, but there’s no point in using the limited time you might have in any training week — you only have so many sessions — to workshop all of them. So you pick a “menu” of what you’re going to use to make sure you can focus on getting them right. That menu might have four or five builds based on numbers and intent — are we launching off the lineout or mauling — and you try to get those nailed down, with obvious scope to adjust to something else if you’re under pressure.

One issue I’ve had with the Irish lineout and the calling of it specifically is how often we tend to double down on a lineout call that didn’t work on the previous one. We use it almost like a double-bluff, as in, you won the last one, so we’ll show you the same shape again to try to use your success against you.

That was a big issue here.

But let’s go through the lineouts and see what we see.

The first lineout was pretty clear for me; an error from Ryan Baird, or a lack of clarity on the call coming from Tadhg Beirne.

This is a five-man “thread pull” where Baird walks up as the middle jumper, before darting to the front with Ryan weaving behind as a lifter. Looking at the reaction of Ryan, Beirne and Furlong, this was going to be a simple pace jump at the front to win easy possession, drop it back to Gibson Park, who will likely hit Crowley for a kick reset up the field. Either that or a set maul to bind the All Blacks into a maul set, before doing the same kicking plan.

Beirne and Furlong are shaping to block the All Blacks’ lineout from pressing through on Gibson Park, rather than getting into a maul build, so I think this one was likely either an error from Baird or a timing issue on the trigger.

It looks bad, though, and immediately would have put the wind up James Ryan, who became the primary caller after Beirne was red carded a few moments later.

How did we get that one so wrong?

Even then, he would have noticed that the All Blacks competed heavily on the front of this lineout, the very first one, so that will be in his mind, too. They’re going after the front.

On the next two lineouts, we ran more or less the same call again — almost like, we’re going to get this one right — albeit with Conan replacing Beirne in the lineout in general, but Baird’s role in the walkup. We moved to a 5+1 build here with Van Der Flier as the +1 to compensate for being down a lineout forward. On the first, Conan weaves to the front, Baird feints to jump, before Conan jumps in his place — a timing feint.

On the third lineout, a few minutes later, we duplicated the first with a “thread pull” and Conan jumping at the front.

The second was a maul feint and break, the second was a full maul before a break, but it won’t have escaped Ryan’s notice that the All Blacks have competed at the front on all three of these and got close.

From a role perspective here, Baird has already replaced Beirne’s lineout positioning on these calls, with Conan replacing Baird.

Three lineouts, the same base structure, two successful takes — all at the front — and the threat of heavy contesting to come from the All Blacks.

On the next lineout, deep in the All Blacks’ 22, we went to the same 5+1 structure but without the thread pull element.

The All Blacks weren’t going to compete on this one — Jason Ryan, the All Blacks forward coach, puts a huge focus point on maul defence in this zone — so it should be a clean take, but it’s not a good throw by Sheehan. Baird has to adjust mid-air and does well to bat it back, and we score from this one.

But that’s the same shape again, and the All Blacks will be well aware of the cues.

On the previous five-man shapes — you normally use a five-man to limit the scope of the opposition contest as their heavy lifters usually can’t cover the full 10m — Ethan De Groot was locked onto Andrew Porter at the front, looking for his lifting cues.

It’s no secret that Porter is Ireland’s most effective lineout lifter and Ethan De Groot would fill a similar role for the All Blacks on the defensive side of the ball.

De Groot is looking for the cues the All Blacks would have scouted in advance. How deep does Porter sink when he’s lifting? How does he shape when he’s feigning to lift?

Porter had been a lifter on every one of Ireland’s lineouts to this point, so if you get his actions down, the All Blacks front lifter, in combination with Holland going on Sheehan’s throw trigger, gives them a great shot at getting to the throw window at the same time as Ireland’s jumpers.

Ireland were starting to feel the pressure. Ryan can see De Groot locked onto Porter and he’s well aware that this, essentially, is an attempt to choke off the front of the lineout but Ireland can’t go to bigger builds until Henderson can replace Beirne after 20 minutes.

Near the end of that red card window, we used a four-man lineout — the ultimate sign that any team is worried about the counter-launching of the opposition — on the next lineout, and just tried to beat the All Blacks into the air.

This is a good, pacey jump from Baird, and the All Blacks were lucky not to concede a penalty for jumping across in this instance.

On the next one, we’re still using the main concept. Five-man lineout, or a five plus one, but the All Blacks are getting closer, and we’re having to use more feints and cut-outs to throw them off.

Watch De Groot on this one.

The throw is called crooked, but that tends to happen when you have multiple feints. At this point, Ryan is still reacting to the red card and the loss of Beirne from his role. Baird has a more complex role at lock, and Conan is not a natural “lifter” even though he’s a decent secondary jumper.

In this instance, I think leaving Sheehan on the line for those extra few seconds, coupled with the contesting he’s seen on every throw since the start of the game, has spooked him a little.

Sheehan tends to have this “our side” release in his throw. I’m not sure whether it’s a subconscious thing that creeps into his game to spring off the line, but when the opposition is contesting like this, it can lead to visibly squint throws.

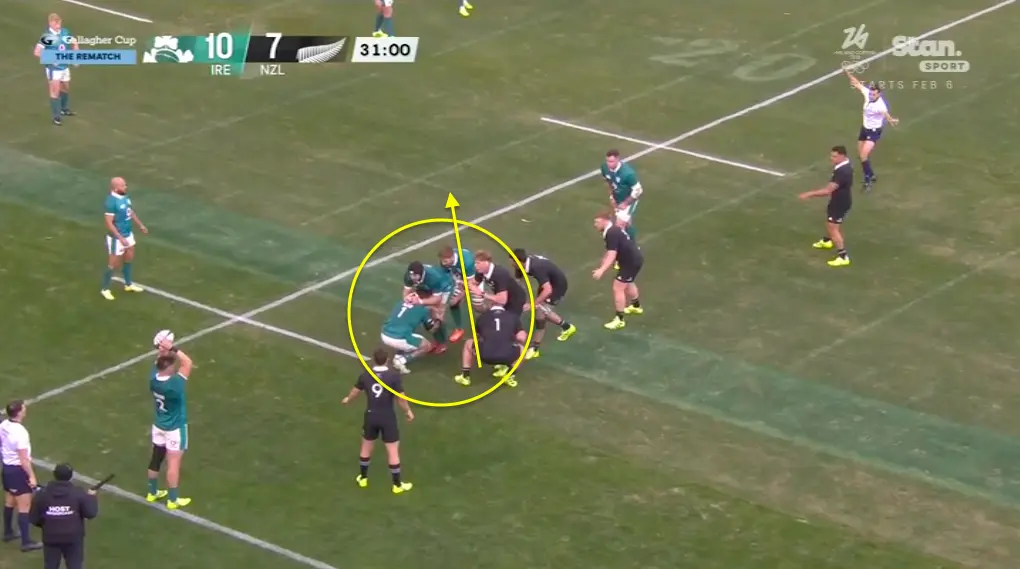

When Henderson finally came on for Beirne, we were able to settle back into our pre-game roles, and that was visibly on the next throw, half an hour in. At this point, we’ve used Porter on every single lift and the All Blacks are wise to it.

Baird, in this instance, essentially tells the All Blacks that he’s going to jump by pressing Porter down before the throw. He wants every bit of launch Porter can give him, and is clearly worried about Holland.

This is a battle between De Groot and Porter at the front, with Lord tucked in behind Holland, marking Henderson for the step back. Porter has been used on every single lineout so far. We know it, so do the All Blacks.

In this instance, De Groot is always shaping to lift Holland across because the only place Ireland can throw this is to the front.

It forces a spill from Baird under pressure, with Henderson half-botching the back lift.

The secret is out.

But we’re still using the same lineout build. James Ryan went off for an HIA late in the half, so once again, we had to adjust. With Henderson calling, we went to another four-man, again with Porter lifting.

It’s executed well, but the All Blacks are right near the throwing window again.

On the next three lineouts, they would finally make this pressure count because we kept going back to the same structure. We used the exact same call twice in a row, losing both, before adjusting after half-time to a similar concept and losing that one too.

From there, we went to the “thread pull” at the front twice, and that same feint action, but this time to a six man build that we mauled pretty well from — it was probably our most effective lineout of the day.

What this tells me — and this is just my read on it — is that we have a calling issue, an over-reliance on Porter as an elite lifter and what I think are budgeted involvements for Tadhg Furlong to keep him playing effectively in other areas. When you combine that with too many players who are elite jumpers (Baird) or good technicians when it comes to the basics of movement and lifting (Ryan, Beirne, Henderson) but not both, it will become increasingly common that more teams use the All Blacks approach of heavy contesting to spook our systems. When you combine that with the wider need for Josh Van Der Flier to make other elements of our system run when he’s not a lineout option… you can see an issue building.

When you start to run through the options, with Porter as our best and most often used lifter, you start to see how avenues might start getting closed off as this season progresses.

And that’s before you get to our tendency to oversimplify our menu pre-game, and then repeat calls back-to-back.

Whatever else happens, the lineout has to be right for Australia and South Africa. The ingredients are there, broadly speaking, but I can’t help but feel like we need a super-sized banker option at lock to ease the pressure on other roles in our lineout build going forward, as well as having a backrow that are all capable of rotating in as regular jumping options.