I’d have settled for a losing bonus point pre-game, but in the end, we had to settle for denying Ulster one. It was that kind of game.

There’s no mincing words here. This was a brutal performance, whether key guys were rotated out or not. Tactically, we looked naive, unable to execute the core basics of something that might even be considered a gesture towards a coherent attacking structure. Our heads collectively looked thoroughly melted at key points of this game, with multiple players’ body language telling you the final result long before the scoreboard did.

Belfast is a difficult place to go. It’s a difficult place to go when you’re fully loaded, never mind half-rotated. Ulster, on a roll and fully going after this game, blew us away in the second half and left us with nowhere to hide. Whatever you think about this, however negative, you’re probably right.

The thing that bothered me most, while I was drinking pints in Centerparcs that were so expensive I could literally feel my wallet taking hit damage (oof! urgh! ugh!), was that we looked so daft. Selection-wise, we were always going to be up against it here, but that doesn’t mean it had to look this easy for Ulster, especially in the second half.

Before the game, I wrote about the importance of Munster kicking well and often to limit the damage of Ulster’s attacking progress.

Ulster’s LBR doesn’t automatically drop because they kick; it drops when we force them into long, low-separation possessions. Their kicking is often a mechanism to avoid that tax.

So we want to deny:

-

- broken-field returns with disorganised chase,

- soft penalties that convert a 40m kick into a lineout on our 22,

- and transition tries off a single isolated carry. We need to be kicking that carry, if that makes sense, by reading the position it starts in. If we’re between the 10m lines, we need to reset and kick off #9 or #10, ideally.

We didn’t kick well enough, and we didn’t kick often enough. As a result, we lost almost every single kicking battle we engaged in, largely due to kicking too long, kicking too late in the sequence, or allowing Ulster to gain separation on transition.

Here’s a decent megamix of poor kicking, poor chasing and overplaying in key areas.

The first clip is a great example of an absolute dud pass to Dan Kelly, so he could be tackled two on one for some reason with no ruck support, and a scrappy unstructured sequence afterwards that looked like we’d met in the car park before the game for the first time.

Then look at Ulster kicking really well, pressing our back three, and forcing a penalty. Then it’s a megamix of poor Munster kicking that gives our chasers no room to impact the defenders, and Ulster doing the exact opposite and moving up the field every single time.

The meta of the modern game is telling you in those clips that we are playing a game that was out of date in May 2025.

Watching live on my phone from a pastiche American restaurant in Centreparcs that did overpriced and underspiced chilli, along with Rockshore for €7.50 a pint, it felt like we went into the game with a hint of tactical naivety, but watching it back, it became clear that what I was actually watching was our halfbacks unable to manage the game as it laid out before them.

There was absolutely no direction to our play; just bad instincts playing out with worse execution. It was almost inevitable that we were going to give Ulster kickable penalties, but we had to make sure that we didn’t panic and try going through long-range on-ball sequences in weather that was going to bite at everyone’s fingers and invite errors.

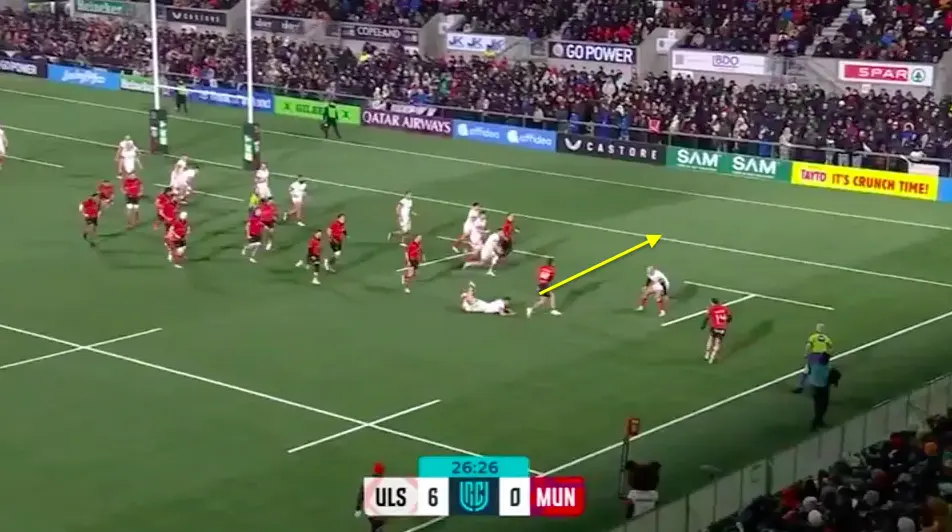

Here’s a moment from the second half in the sequence right before Ulster’s second try. Try to pick the moments when you feel Munster should have dropped back and kicked off #10 to compete in the air.

At least two phases before that daft pass to no one in particular that Dan Kelly just happened to take, before running back into isolated contact as the outside option had disappeared.

Look at what happens.

Turned over under pressure, Ulster kick downfield into a broken Munster backfield, we concede a 5m lineout and end up conceding when we’re stripped of the ball off a 5m scrum. Game over. Losing bonus point, gone. Heads melted.

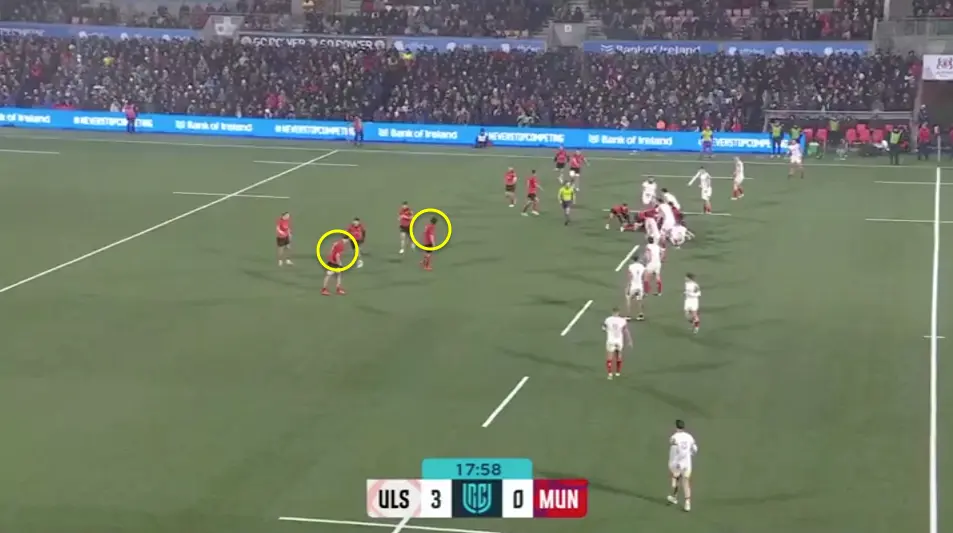

This is a great example of overplaying.

Patterson absolutely has to set for a box kick after that first phase post Hanrahan carry. Has to. The only options after any pass infield are bad.

The only two forwards in the picture are Josh Wycherley and Tom Ahern, with Nash and Nankivell looping around and Haley in the second layer. If the pass to Wycherley isn’t awful, and he can carry straight — what then? Go back through more phases?

He simply has to call in ruck support, use Abrahams as a chaser on the blindside, and then work from there.

Instead, we burn through another two scrappy phases before eventually kicking this back to Jacob Stockdale, which he can take under zero pressure.

Is that the coaches telling the players to go out there and play ball? Or is it halfbacks freezing — literally and metaphorically — under pressure because what they do best isn’t playing a conservative kicking game?

Paddy Patterson is a lot of things, but a tactical game controller isn’t one of them. Neither, you could argue, is JJ Hanrahan. What they see out on the field seems to be the opposite of what the current game demands of them.

Even when our attacking created opportunities, we seemed to look for the extra pass more often than not.

Alex Nankivell had a good game for Munster here, or a decent one at least, but when a gap opens up in front of him like this, his first instinct has to be going for the tryline instead of throwing a pass that actually lets Jacob Stockdale’s positioning off the hook.

At 6-5 or 6-7, we could have been right where we wanted to be in pressuring Ulster for the rest of the half. Instead, we seemed to be intent on making sure our system made us look smaller and more undersized than we were in reality.

We played right into Ulster’s best game, and our worst one.

If I reduce this match to one theme, it’s this: we tried to solve a field-position problem with ball-in-hand. We didn’t kick enough for the kind of game it became in the conditions, and we ended up playing too much rugby in the wrong zones — which is exactly how you turn a difficult away day into a 28–3 washout.

Ulster beat us on where the match was played, and everything else flowed from there.

The most damning stat, for me, is the possession split by zones:

- Ulster: 41% of their possession in our 22 (and only 8% in their own 22)

- Us: 12% of our possession in their 22 (and 14% in our own 22)

That is the entire game in one picture. We spent 48% of our possession in our own half (14% + 34%). Ulster spent 29% of their time in their own half (8% + 21%). In other words, we played from deep; they played on our line. We needed the exact opposite.

We didn’t kick at enough volume or accurately enough to burn Ulster’s phases, and the game we chose onfield naturally flowed from there.

We didn’t earn enough Entries

Ulster had 13 x 22 entries. We had 2.

Our points-per-entry (1.5) is basically the same as theirs (1.6), which matters because it removes the automatic, easy excuse. This wasn’t a finishing problem. It was an access problem.

If we are only entering twice in an 80-minute match, we can talk about shape and selection all we want — but the root cause is territory and pressure. That comes back to kicking in January 2026, and it’ll be the defining factor of the next few weeks.

Ulster’s attack numbers are not just bigger — they’re more forceful:

- Carries: 147 vs 86

- Post-contact metres: 375m vs 143m

- Linebreaks: 8 vs 1

That’s Ulster getting 2.55 post-contact metres per carry; we’re at 1.66. They’re generating linebreaks at roughly 5.4 per 100 carries; we’re at 1.2 per 100. We played altogether too much rugby for no reward whatsoever.

We asked our phase game to do a job it wasn’t winning in the collision. If you are not bending the line, the extra pass and the extra carry are not building pressure — they are building fatigue, error, and defensive load.

The defence numbers tells you how the match felt in real time:

- Tackles made: 209 (us) vs 126 (them)

- Missed tackles: 33 (us) vs 11 (them)

- Tackle completion: 86% (us) vs 92% (them)

That is the profile of a team defending for long stretches, often with zero control, and paying for it in broken edges and repeated re-entries. Patterson and Abrahams seemed to be defending the same wing almost constantly and were driven through repeatedly. We were coming undersized relative to Ulster’s back three and, arguably, in the pack too, so we needed to make sure we were giving those players the best chance possible by breaking up the field if we were going to commit to off-ball rugby, as I think we intended to do on the night. We didn’t execute, and then we didn’t adapt. Our discipline then told the story.

When we’re making 209 tackles and conceding 10 penalties, we’re giving Ulster repeatable entry starters: kick to corner, lineout pressure, multi-phase in our 22. That’s exactly how a team gets to 13 entries without needing anything miraculous.

“But we kicked 21 times” — we still didn’t kick enough

We both — Ulster and ourselves — kicked 21 times, but that’s the point: we matched Ulster’s kick volume in a match where we were the team that needed to flip the pitch.

Our kick-to-pass ratio (1:6.6) suggests we kicked relatively often, but the match context was that we still played too much rugby because:

- We were playing from our half for almost half of our possessions.

- We weren’t winning collisions (1 linebreak, low post-contact output).

- We were under heavy defensive load (209 tackles).

- We were bleeding penalties (10), which hands the opposition territory anyway.

In that environment, “enough kicking” is not a raw number. It’s a commitment to taking the ball out of the game in the wrong areas, forcing the opponent to start long, and making them repeatedly earn access rather than receiving it by rote.

We didn’t do that. We tried to move the ball to solve a territorial and ever-growing scoreboard deficit, and a fired-up Ulster were happy to defend it, absorb it, and then play the second half in our 22.

What we should have done instead: the kicking framework

If I’m framing this purely through the “we played too much rugby” lens, the corrective is clear:

Exit-first mindset

When we receive in our half, we prioritise:

- distance (touchfinders and low-risk clearances),

- structure (chase connected, ball dropping on defenders as the chase arrives with ruck pressure following),

- no counterpunch opportunities (no soft receipts, no fractured lines).

Earlier kicking triggers

If we’re not denting the line early in a possession, we don’t “work harder” for the same outcome.

- If the first 1–2 carries are neutral, we kick before we hand Ulster a turnover. Why are we playing a tip-on here? To Jean Kleyn? What is the function of that?

Make them play long

Ulster’s 41% possession-in-our-22 is the stat we can’t live with. The direct antidote is to force them into:

- longer exits,

- more plays from their half,

- and fewer “two-penalties-and-you’re-back-on-our-line” sequences.

Discipline as a territory KPI

If we concede 10 penalties, it doesn’t matter how well we kick — we are gifting them corners and shots at goal. For us, discipline is not separate from kicking; it’s part of the same territorial system, and as much as we panicked at halfback, we gave away far too many not rolling away penalties here, too. One feeds into the other.

We didn’t lose because we lacked effort or because players didn’t care or any of that shit. We lost because we played a ball-in-hand game in the wrong areas almost constantly, against a side that was winning contact on both sides of the ball and living in our 22.

If we want a different outcome in a fixture like this, we need to be comfortable saying: we are going to kick more, earlier, and with clearer intent — and we are going to make the opponent build their way to our line. In this match, we let Ulster start too many sequences already inside our red zone when it counted. Once that happens, everything else is irrelevant.

Losing a game like this isn’t a season killer, by any means, but it does call elements of our squad into question, as well as our coaching approach before the game.

Did we come into the game looking to play this many phases in brutal sleet on a 4G pitch? Or did the players selected fail to execute that? Is it both? If it’s the former, the fix is easy; selection and recruitment will fix it. If it’s the latter, we need a big rethink.

Either way, answers will be needed quickly and have to be visible on the field before our strong start to the season warps into another dogfight.

| Players | Rating |

|---|---|

| 1. Josh Wycherley | ★★ |

| 2. Diarmuid Barron | ★★★ |

| 3. Michael Ala'alatoa | ★★ |

| 4. Jean Kleyn | ★★★ |

| 5. Fineen Wycherley | ★★ |

| 6. Tom Ahern | ★★★ |

| 7. John Hodnett | N/A |

| 8. Alex Kendellen | ★★ |

| 9. Paddy Patterson | ★ |

| 10. JJ Hanrahan | ★ |

| 11. Thaakir Abrahams | ★★ |

| 12. Alex Nankivell | ★★★ |

| 13. Dan Kelly | ★★ |

| 14. Calvin Nash | ★★ |

| 15. Mike Haley | ★★ |

| 16. Lee Barron | N/A |

| 17. Jeremy Loughman | ★★★ |

| 18. Conor Bartley | ★★★ |

| 19. Jack O'Donoghue | ★★ |

| 20. Brian Gleeson | ★★★ |

| 21. Ethan Coughlan | ★★ |

| 22. Tony Butler | ★★ |

| 23. Sean O'Brien | ★★ |