A lot has been made of Leinster’s — and Ireland’s — hangover post Lions over the last few months.

The reason for this is simple.

They don’t look the same. Opponents that Leinster have dismissed in the last two or three years with little hassle are causing them incrementally more problems. You just have to watch their games to see it.

Whatever about their Lions-afflicted start to the season in South Africa, they have laboured for long periods in their wins over the Zebre, Harlequins and Leicester. They arguably should have lost to Ulster and the Dragons, and that’s before we talk about decisively losing to Munster in Croke Park a few short weeks ago.

So when people talk about Leinster not looking right, it’s this. Things that used to be routine, functional, easy, even, are now… not. In the last four years, you typically expected Leinster to have difficult games against either fully-loaded South African sides at altitude, Toulouse, prime La Rochelle or perhaps a particularly motivated UBB.

That is not the case so far this season, but, in a way, its performances, moreso than just results. Sure, they’ve lost three games before January when they typically might lose three before May, but they’ve managed to dig out wins, too. Despite playing poorly in almost all of these games — the only one where they’ve looked like the Leinster of old was against a feckless Sharks side in Dublin — they’ve still managed to find a way to get over the line, which isn’t a surprise.

While I think it’s fair to say that this iteration of Leinster is in something of a decline, that doesn’t mean they’ll fall asunder overnight.

Assigning everything to the Lions (or even that loss to Northampton last season as some kind of six-month-long hangover), though, is something close to wishful thinking. The reality is that the vast majority of this Leinster core have been seeing incredibly heavy usage for club and country over the last five years, most of that same core is aged 30 or above in most cases, and that’s a bill that comes due gradually, and then all at once. We know what that’s like in Munster. Just cast your mind back to that spell between 2009 and 2012 for an idea of what it looks like. Great players can’t keep going forever, but you only really see the decline that always comes in hindsight.

In practical terms, I think that means that Leinster’s top-end, European Cup finalist-tier consistency is likely to be in the rear-view mirror, but they are still an incredibly dangerous opponent on any given day, home or away, and you’d be absolutely daft to think anything different.

But now they are a team with a clear systemic weakness, and the only question is whether or not you have the quality to exploit it. The relevance to this game is clear; do Munster have the wherewithal to activate that weakness — as we did in Croke Park — at home? History would suggest we don’t, but in the context of the last few years against this Leinster team and in the context of our home games this season.

Munster Rugby: 15. Shane Daly; 14. Calvin Nash, 13. Tom Farrell, 12. Alex Nankivell, 11. Thaakir Abrahams; 10. Jack Crowley, 9. Craig Casey; 1. Michael Milne, 2. Lee Barron, 3. Michael Ala’alatoa; 4. Edwin Edogbo, 5. Tom Ahern; 6. Tadhg Beirne (c), 7. Jack O’Donoghue, 8. Gavin Coombes.

Replacements: 16. Diarmuid Barron, 17. Jeremy Loughman, 18. John Ryan, 19. Jean Kleyn, 20. Fineen Wycherley, 21. Paddy Patterson, 22. Dan Kelly, 23. John Hodnett

Leinster Rugby: 15. Ciarán Frawley; 14. Tommy O’Brien, 13. Rieko Ioane, 12. Robbie Henshaw, 11. James Lowe; 10. Harry Byrne, 9. Jamison Gibson-Park; 1. Andrew Porter, 2. Rónan Kelleher, 3. Thomas Clarkson; 4. Joe McCarthy, 5. James Ryan; 6. Max Deegan, 7. Josh van der Flier, 8. Caelan Doris (c)

Replacements: 16. John McKee, 17. Paddy McCarthy, 18. Tadhg Furlong, 19. Diarmuid Mangan, 20. Scott Penny, 21. Fintan Gunne, 22. Charlie Tector, 23. Andrew Osborne

What is that weakness?

Leinster are a team that struggles when their opponents kick to them at high volume. At a systemic level, the reasoning for this is simple and obvious. Leinster like to defend your phase play and force knock-ons in contact or counter-ruck, so that they can then kick downfield, forcing you into botched exits or conceding holding on penalties under pressure. Almost everything they are really good at is tilted towards this, with the idea being that they can get you playing their game, which is based on set-piece strike plays, penalty ladders and pressure.

When they are in control of the scoreboard, they will kick almost everything off #9/10 and look to compete in the air, which will force knock-ons or extended lineout battles. They love competing on opposition lineouts and using a hyper-aggressive loosehead walk-around to force penalties at the scrum. Porter bores in, the Leinster back five walks around to generate forward movement, penalty.

When it works, it’s hugely effective. When it doesn’t, or their kicking game doesn’t produce returns, or they can’t produce a scrappy lineout, they can look incredibly blunt.

So why are teams kicking to them at volume?

Opponents always kick more than Leinster

In every game I tracked this season, the opponent’s kick-to-pass ratio is more kick-heavy than Leinster’s (lower denominator = more kicking).

To make that into something tangible, we need to convert kick-to-pass into kicks per 100 passes:

- Across these 9 matches, opponents average ~25.5 kicks per 100 passes versus Leinster ~14.0.

- That’s opponents kicking at roughly 1.83× Leinster’s rate in these fixtures.

This is a strong, direct proxy: teams are choosing a kick-volume plan against Leinster as a default. In practice, this means that everyone has realised that this is a way to suppress Leinster’s preferred game model. They have all looked at Leinster’s games and data, realised the obvious metrics in there, and chosen this approach, even teams like Ulster, who have chosen not to kick at volume against everyone else except Leinster.

The “why they do it” indicator: Leinster don’t punish kick-receipt possessions with tries

From Leinster’s seasonal data so far from OPTA:

- Kick-return tries: 7.4% (low)

- Own-half try share: 11.1% (low)

That combination tells opponents: “Kick to them—there isn’t a big counter-attack tax.” Leinster’s model is to take opposition kicks, reset and then kick in return rather than attacking in transition. This might change as Ioane gets settled into their system, but it’ll be hard for them to do that with him playing in midfield. Neither Lowe nor O’Brien are dangerous transition runners at range, and both are far more comfortable chasing crossfield kicks or, in Lowe’s case, being a dangerous carrier in edge spaces off a bridge pass.

When opponents kick big, Leinster get dragged into low-yield, ruck-heavy attack

Using our rucks + linebreaks LBR method, you can see a pattern that aligns with a team being pinned/backfield-pressured and forced into slower, tighter possessions:

In their 9-game sample so far this season, when opponents kick at 25+ kicks per 100 passes (roughly kick-to-pass ≤ 1:4.0):

- Leinster entries drop (12.5 → 9.0 per game on average)

- Leinster points per entry drop (3.0 → 1.84)

- Leinster linebreaks per ruck drop (0.1016 → 0.0670)

- Leinster rucks per linebreak rises (10.0 → 17.6)

That is the statistical shape of a side being forced into volume phase-play without space — exactly what a high-kick plan is designed to create.

The extreme “tell” games

- Stormers (opp 1:3.7): Leinster 5 entries, 0.0 PPE, lineout 75%. That’s what a territory/aerial squeeze looks like when it lands.

- Munster (opp 1:3.3): Leinster 131 rucks, 4 linebreaks (one linebreak every 32.8 rucks), 1.2 PPE. That’s a classic “kicked into a phonebox” profile.

- Ulster (opp 1:3.7): Leinster 127 rucks, 7 linebreaks (one every 18.1 rucks), tight game that Leinster arguably should have lost.

- Leicester (opp 1:2.9): Leinster 1.6 PPE in a lower-event grind.

In the metrics I’ve found this season, the correlation between kicking to Leinster at a high volume and producing lower-quality Leinster performances is clear.

-

Opponent kick-to-pass is consistently higher than Leinster’s — opponents ~1.83× the kicking rate.

-

Leinster don’t convert kick-receipt possessions into tries often, with low kick-return and own-half try shares.

- Leinster’s ability to convert linebreaks into tries is the second lowest in the URC, which scans with most of their opponents kicking at volume — the linebreaks Leinster do get are at range, and they’re not converting those linebreaks at their usual clip over the last few seasons.

-

When opponents do kick big, Leinster’s attack becomes ruck-heavy with a depressed linebreak rate, and their entry/PPE profile tends to soften.

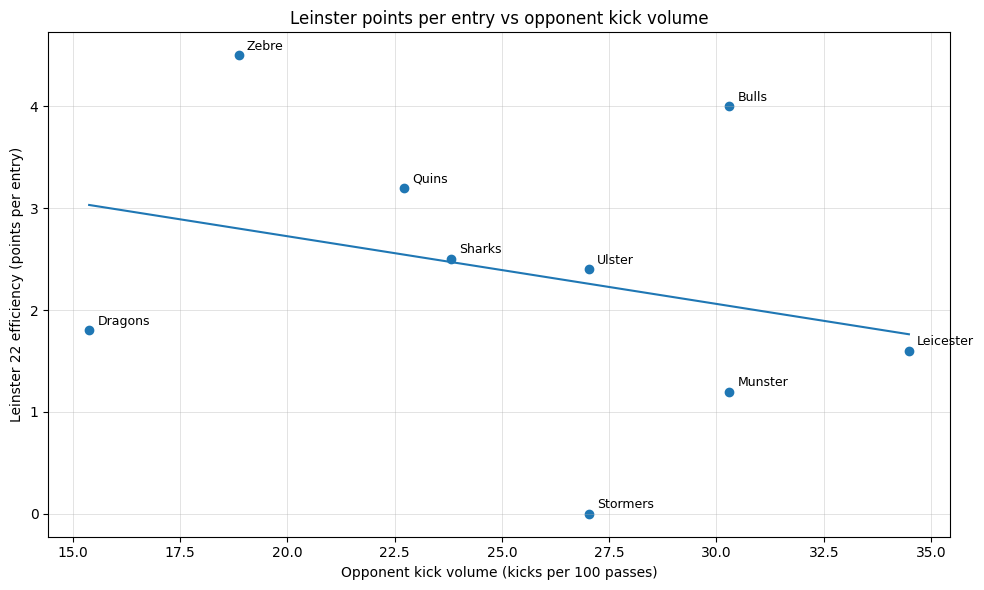

When you plot it on a graph, you see it quite clearly.

Essentially, if you can kick at Leinster at volume, while also having the ability to suppress their phase play, you can shut down their scoring efficiency, meaning you only need to convert at a regular level up the other end to beat them. If you get ahead on the scoreboard, you can kick even more freely and increase the pressure because Leinster’s 22 efficiency directly correlates to the kicking volume they face.