There’s no shame in losing to a good Stormers team playing their first home game of the season in Cape Town.

We’ve seen by now that the South African sides north of the equator are nothing like what they are south of it. The Stormers’ “form” on their European tour was always worth disregarding when assessing their quality. This is not a team built to play on a cold night in Bridgend in September. This team wants to bring teams to Cape Town and beat them (up) there.

But there is shame in how you lose to the Stormers if indeed you have to lose at all. Make no mistake about it, this is a game that Munster could and should have won. I’ve watched the game back four times and my only takeaway is that it’s five points left behind us at best, four going well and two points at realistic worst.

To finish with zero match points is brutal.

We had enough opportunities to win the game twice over but were double-crossed at every point by, without question, the worst lineout in top-division elite rugby.

Our average lineout success rate across this season is 79%. That is buffed by a 100% completion rate against the Ospreys. Exclude that game as the aberration it appears to be and we’re running at 72%.

It’s generally agreed that a truly elite lineout runs at 90% plus. Most good sides operate at 88% plus. Decent sides want to hit 85% plus as standard. Apply these across a season and you’ll generally see the best sides filter into these brackets. Every team has a bad day at the lineout in a season but it’s how you stack up across a season that marks out success – or failure.

I’ll say this; running below 80% is unheard of for a team with Munster’s ambitions. Below 75% would get unit coaches at the Dragons the sack.

But that’s where we are so far this season.

We have had 69 lineouts and lost 14 of them. As a comparison, we have won 53 lineouts. That is to say, we technically retained possession of the ball 53 times at the lineout. Some of those have been regular lineouts, some of them have been scrappy throws we’ve just about managed to claim back with the ball bouncing all over the place. That said, winning 53 lineouts is pretty standard across the league at this stage of the season. The league average is 57. The problem comes with how many lineouts you lose.

The Lions have won 52 lineouts but only lost two of them. Two.

Connacht have won 61 lineouts and only lost four. Scarlets have 59 lineouts won and only four lost.

That is how far off the mark we are currently.

And what’s worse, we have only one lineout steal to our name; we are losing more lineouts than anyone and, on the other side of the ball, stealing fewer lineouts than anyone else.

So why is it happening?

I think at this stage we’re in something of a death spiral when it comes to the lineout and it goes back to last season. Teams realised early on last year – and this was mostly due to having multiple senior locks and hookers missing during the middle of the season due to injury – that if you contest Munster’s lineout aggressively, our structures can’t handle the pressure. Go back to multiple games last season and you’ll see it.

The one that springs to mind first for me is the semi-final defeat at home to Glasgow. What was the completion rate there? 75%. And that’s just a number, right? In reality, it’s almost always either momentum lost, territory lost or minutes of hard work down the drain because the set piece that’s easiest to control wasn’t controlled. And sure, you’re always going to lose one or two here or there because the opposition has pulled out a worldie steal – that happens. What doesn’t happen is losing 25% of your lineouts in a home knockout game.

It doesn’t even have to be a sub-80% game for that to happen. On multiple occasions in Europe last year we had crucial lineouts we had to take but couldn’t. Away to Northampton in the Round of 16, we ran at 81% which, again, is well below what you’d even call decent.

I use the term “death spiral” because teams seem to have worked out that you can kick the ball out against us quite freely – and even concede penalties freely at a certain range – because they know that the more lineouts they contest, the larger the likelihood is that we’ll turn the ball over.

Essentially, teams have learned that contesting Munster’s lineout is a winning strategy that allows them to play with defensive freedom and actively saps energy from us over and over again. I think that this is a result of constant opposition analysis – especially as defending URC champions last season – and that we haven’t adjusted in line with the level of detail that our opponents have applied to us.

I’ll be doing a TRK Classroom livestream this week on the lineouts so I won’t go over it again here after last week. But.

Here’s a good example of what I’ve been talking about since the Leinster game; bad concept, bad execution, massive energy lost at a key time. I’m going to show you two lineouts.

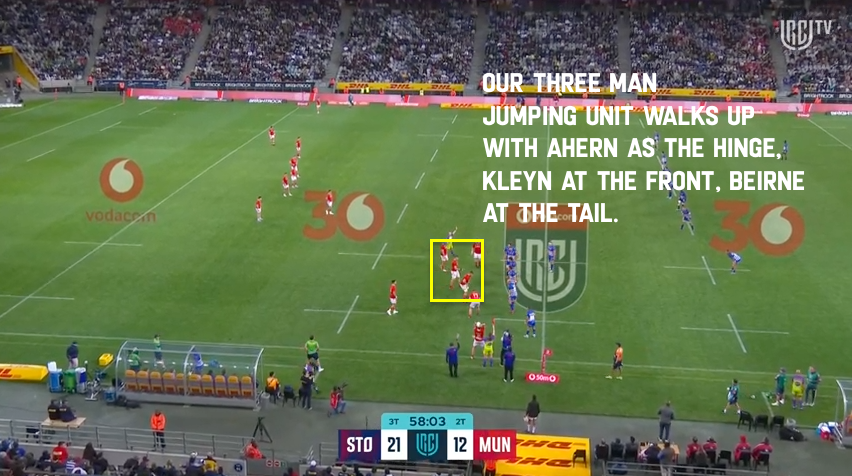

To set the scene; the first lineout happens around the halfway line and Munster are losing by nine points with twenty minutes left, more or less. Here’s the structure.

Our jumping unit at this stage of the game is Beirne, Kleyn and Thomas Ahern.

So, one of the best locks and lineout forwards in the world who often calls and is a primary target for an Irish team ranked #1 in the world and are current Six Nations champions, a World Cup-winning front jumper tighthead lock and a 6’9″ unicorn freak athlete half-lock with a wingspan closer to Giannis Antetokounmpo than Devin Toner.

We have Gavin Coombes and Alex Kendellen arrayed in the midfield to force a compression in the opposition midfield or to secure a hit-up to catch the Stormers transiting the ruck, as we had done a few times in this game to this point.

Here’s the lineout;

It’s a fairly simple one. There’s no wild cut-outs or anything like that. We’re trying to hit the back of the middle or the tail with Beirne stepping into a back lift by Archer and Ahern stepping in from the hinge in the middle of the lineout to assist as the front lifter.

The deception here is that Ahern starts as an “obvious” target in the middle who can also lift Kleyn at the front so, in theory, Stormers have to cover all possible options with their own three jumping options. The whole advantage of a five-man lineout is that you have a dominant position in the “shell-game”. You know where you’re throwing, the opposition doesn’t, and they don’t have enough numbers to put two pods in the air.

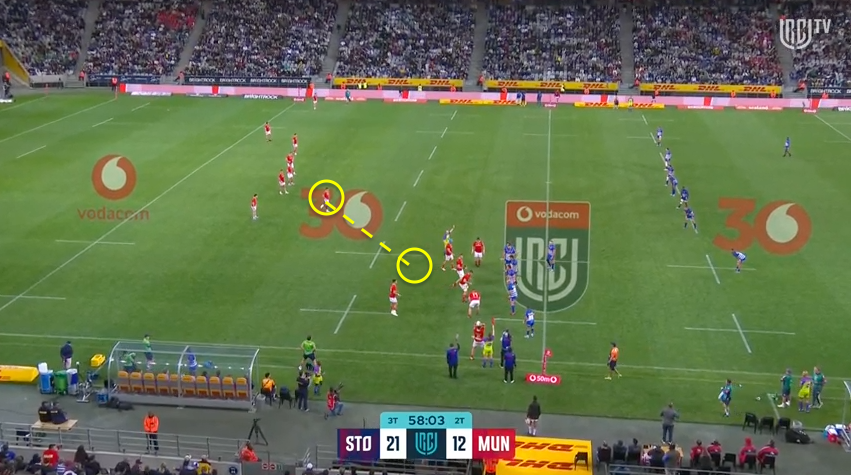

But we’ve given the game away before the ball was thrown in.

Look at the gap between Burns and Murray here. If the plan is to hit the numbers in midfield – which it must be, or why would they be there – the only possible place we could be throwing the ball to is the tail.

Otherwise, there’d be no realistic way for Murray to find Burns. As a result, Schickerling is mirror marking Kleyn at the front to copy his movements. Kleyn is in a lateral position to sell the possibility of a lift on Ahern and a possible jump at the front, and Schickerling is guarding that option.

They are gambling that Ben Jason Dixon – their hinge player – can react as a counter-jumper or lifter if needs be if we go to the middle or tail, which they are pretty sure we will.

As a result of that surety, Ben Jason Dixon can lift Van Heerden before Ahern gets to Beirne, which gives Van Heerden more elevation relative to Beirne. While all of this is happening, Beirne starts to stall out on his launch which means he can’t meet the arc of the ball in the window where he might be able to reliably play it.

When you see a jumper begin to arc off-centre like Beirne here, it means that the primary lifter – in the case of a back lifter who engages the lift first – isn’t getting the right power into the lift. But even then, the structure of the lineout that sees Ahern having to make two steps before joining as the secondary lifter doesn’t seem optimal to me; asking him to cover too much space. I see why he’s there – to bait the Stormers into using Ben Jason Dixon as the counter-jumper – but the Stormers weren’t buying.

Now for the second lineout.

This was the most important lineout of the game because there were only eight minutes left and we’d scored a few minutes earlier to make it a two-point game. If we could take this lineout, we had the impetus to start pressuring the Stormers around their 10m line.

We went for the same five-man set-up with two changes;

- Beirne and Ahern had swapped positions on the walkup.

- Ahern was standing one step away from Beirne, who is the hinge lifter in this variant.

Everything else is the same. Same midfield lineup, a slightly closed distance between Burns and where we want Coughlan to take the ball and the same position for the #4 lock (Wycherley in this case, as Kleyn had gone off at this point).

The compressed lineout works in getting their hinge player to jump – he jumped on his own with no lifter – but Scannell, who came back on the field a few seconds before throwing this due to an HIA on Clarke, underthrew the ball so we didn’t get to use Ahern’s height against a player that only had one lifter.

My point is that it was the same concept, used in more or less the same position and it drew the same response from the Stormers. Our adjustment to the Stormers’ previous counter was to get our tallest jumper into a position to take the ball at the tail, rather than using Beirne, for example, in the middle of the lineout.

We had the same requirements; a five-man scheme hitting the scrumhalf on the run to move the ball into the middle of the field and we chose to go about it in broadly the same way. Of course, the Stormers pressured us. Why wouldn’t they? We showed them the same thing in the shell game and hid the ball under the same cup.

Our lifting isn’t great. Some of that has to do with the props we’re using which, in the above example, are either in their mid-30s or academy players. A 36-year-old Stephen Archer isn’t going to be as explosive a lifter as he was even two years ago. Does Oli Jager or a fit Roman Salanoa lift Beirne quicker and straighter on the first lineout? Yeah, probably.

But the bigger issue, for me, is that there’s a disconnect between what we want to do in the backline and what our lineout has to do to facilitate that. In both these instances, we wanted quick sling ball to the scrumhalf so we could pull the Stormers’ heavy defence into the middle of the pitch and my guess is they’d try to swing back the other way with a kick pass play to isolate their winger back where the lineout took place. It seems like we only had one structure that produced that type of ball, though. Is that why we used the same motion twice with minimal changes?

That then comes back to the menu we have coming into the game and in general. And the finer details of our structures. It seems like, to commit numbers for the opposition counter-pods we often leave our lifters too much ground to cover on their routes. I’ll go over that more on the live stream on the €5 tier this week.

Do the players have confidence in our lineout? I’m not sure they do. Until that changes, nothing else will.

***

Our lineout being a little better than a raffle ticket at its worst was the core issue in this game. Positions that were hard-earned ended in a turnover of possession a little over half of the time. When you have 14 lineouts that means you had six that ended up back with the opposition. Each of those lost lineouts is a lost on-ball sequence in their half of the field where we’re not pressuring a leaky, slow defence.

Even then, it feels like other elements of our game aren’t firing on all cylinders either. As with the end of last season, we look desperately one-paced in our outside backline. In this example, we got great turnover ball off an overthrown Stormers lineout but every single player who touched the ball after Kendellen’s pass didn’t have the pace to attack the obvious holes in the Stormers’ defence or didn’t trust the player outside them to have the pace either.

They were all right.

You can carry one relatively slow player in a transition moment like this, but not three. If that’s Abrahams or Kilgallen, the outside break is on almost immediately.

In general, we find it very hard to get separation from a scramble defence. In this moment, I’d love to see Daly get ahead of De Wet so he can isolate Willemse in the backfield.

The same goes for O’Brien after he gets the pop pass from Daly; that elite acceleration isn’t there.

I think our pace issues are so pronounced that we make objectively bad pass decisions because we aren’t confident that the linebreak will develop. In this example, Crowley should probably hit the ball flat to O’Brien but I think he double-crosses himself and goes into the layer because he doesn’t trust that O’Brien can advance enough in the linebreak to avoid a turnover on the next phase.

It’s an objectively poor decision but I get it, in a way. O’Brien probably doesn’t advance beyond the halfway line on this pass. Can he find a killer pass inside or outside him before that? Good question.

Pound for pound, this starting XV is probably the least explosive provincial side so we need to be able to hurt teams on the edges, while also being ruthlessly well-drilled at the lineout and in contact.

A slight bugbear of mine is that we often don’t play like the undersized team we are and, as a result, I think we end up punching below our weight, especially once we get deep into the opposition’s 22. Here’s a good example where O’Donoghue stays a little wide on Kendellen to attack the support tackler but, in doing so, sees Kendellen get smashed with a two-on-one tackle.

O’Donoghue then cleans out nobody (-2 points) and we get less than ideal ball. It’s like we’re constantly threatening a tip-on or offload in the most low percentage spots on the field.

This one in the second half was a great example of hanging a carrier out to dry.

The first collision is OK – Clarke does well, as do Kendellen and Coombes. The second phase of this clip sees Beirne isolated for a double tackle because the guys inside him (Kieran Ryan) and outside him (Stephen Archer) are absolutely no threat to the Stormers’ defence so they can swarm for a double tackle.

What is Beirne supposed to do here? Does the Stormers’ defence care if he pops a tip-on to either of those players in the pod with him? No, they don’t.

When you look at the Stormers – a bigger, more powerful team with more explosive front-five athletes – in the 22, they play like we should be.

The 125kg Adre Smith latches and drives Keke Murabe into contact. Ben Jason Dixon takes the next carry and he has Thuenissen on his back touch tight ready to latch and secure the ball with a 6’8″, 120kg JD Schickerling narrow on his outside. Our tight contact work needs to improve to allow us to play with some level of stability.

I think it’s fair to say that our current front five is drastically underperforming, physically. In a way we have “carry” – a ridiculous term for one of the best players in the world but I think it fits when it comes to the physical battle – Tadhg Beirne, a smaller, lighter half-lock to make our available pack work at the moment.

Ahern is best suited as a middle and edges runner with a huge lineout focus – it’s where he’s best. But that then means that we need to have power hitters elsewhere. We looked better on phase play once Coombes replaced O’Donoghue because Coombes could balance out our heavier carrying. Alex Kendellen did a decent job too but the focus comes back on the rest of our front five.

We understand that loading up Scannell, Loughman, Archer and John Ryan for too much carrying or collision work at this stage is a bad use of their strengths as players.

This can only be rebalanced by getting more heavy firepower into this pack; namely Oli Jager, Edwin Edogbo and Brian Gleeson.

Ultimately, this game was lost because we were holed below the waterline by an underpowered front five in phase play, a lineout that would scatty in Japan’s League One and a lack of killer pace as a whole in the backline.

All of these can be fixed but the question is when because the clock is ticking.

| Players | Rating |

|---|---|

| 1. Jeremy Loughman | ★★ |

| 2. Niall Scannell | ★★ |

| 3. Stephen Archer | ★★ |

| 4. Jean Kleyn | ★★ |

| 5. Tadhg Beirne | ★★★ |

| 6. Tom Ahern | ★★★ |

| 7. Alex Kendellen | ★★★ |

| 8. Jack O'Donoghue | ★★ |

| 9. Conor Murray | ★★ |

| 10. Jack Crowley | ★★ |

| 11. Shane Daly | ★★ |

| 12. Sean O'Brien | ★★ |

| 13. Tom Farrell | ★★★ |

| 14. Calvin Nash | ★★ |

| 15. Mike Haley | ★★ |

| 16. Eoghan Clarke | ★★★ |

| 17. Keiran Ryan | ★★★ |

| 18. John Ryan | ★★ |

| 19. Fineen Wycherley | ★★★ |

| 20. Ruadhan Quinn | ★★★ |

| 21. Ethan Coughlan | ★★★ |

| 22. Billy Burns | ★★ |

| 23. Gavin Coombes | ★★★ |