The beauty of the scrum is that you always have an out, regardless of how it goes.

If it goes well, the opposition usually complains about rampant illegality, and you laugh at their feebility. The same is always true in reverse. We weren’t destroyed in the scrum; the opposition was cheating. And, worse again, the daft hoor of a ref missed all of it. They then get to laugh at our feebleness.

It’s the Dark Arts, after all. Unknowable; unless you’re on top.

In Ireland, the scrum hasn’t really been a focal point in a real way since the Disaster at Twickenham in 2012. Perhaps you recall that day; maybe you don’t. I won’t overfocus on it, but it’s safe to say that it was an annihilation so complete, so visible, that the IRFU actually announced an opening for a scrum coach in the weeks that followed. Worse again, we had to endure the rinsing that followed, much as we’re doing this week.

From an English playing side, Alex Corbisiero later described the game as a predator-prey situation. In his 2020 Irish Times interview, he admits he was already “getting the better of Mike Ross” before the neck issue forced the change and that when Court arrived at tighthead, “what followed was relentlessly cruel.” Once Tom Court started to turn under pressure, Corbisiero says, “We were like sharks in the water. After the first couple, when he turned in under pressure, that was the trigger. I knew I had him.” Nigel Owens eventually ran under the posts for the penalty try with Irish scrum folded in on itself; Corbisiero recalls seeing Cian Healy “sitting down facing the wrong way — in the middle of the scrum” with “this defeated look on his face”.

That 2012 Six Nations was the last one before the then IRB brought in the Crouch, Touch, Set era to encourage fewer collapses and resets — the extra pause was thought to encourage mistimed hits and instability. The ultimate aim was to remove the “hit” in the scrum, eventually. In 2013/14, that was then changed to Crouch, Bind, Set, which World Rugby’s own material spoke about reducing up to 25% less impact at the elite level, plus a renewed instruction to refs to keep the scrum stationary and square before the feed and police early shoves and crooked feeds more strictly.

Later tweaks — mandatory striking for the ball, a slightly friendlier feed, axial-load bans, time limits to set scrums, banning a scrum option from a free-kick and extra protection for the 9 — were all attempts to keep the scrum as a genuine contest for territory and possession without it becoming an injury lottery or a two-minute reset machine.

But the contest remains.

From a perception perspective, Saturday night was as bad as the game in Twickenham thirteen years ago, if not worse, because no law tweaks are coming to change what happened. In Twickenham, we withered under the hit. Later law tweaks removed it. The laws aren’t coming to save us.

We can rage against that, dispute it, try to claim up is down, and black is white all we like, but a reckoning is coming all the same.

All the sides we want to compete with at the top of the game have been making the scrum a priority for the last 18 months, if not for decades before that.

Those same sides, South Africa included, will have seen Saturday’s game for what it was. Not a distorted refereeing performance, not a bad day at the office; a systemic, baked-in weakness to this iteration of the Irish team.

When Andy Farrell was asked after the game about Ireland’s issues in the scrum and why he wasn’t more proactive with his replacements, his words were quite telling.

I’ll reprint them here.

“Well, obviously, you get advice from what John Fogarty is saying and seeing in real time on the floor. You get advice from what’s going on there. But it isn’t just one side, a scrummage is always about the pack of eight. The pressure also comes on one aspect because we’re under pressure in other areas as well. So, that’s why the pressure comes on; it’s not just on one area.”

Maybe I’m too cynical, but that felt a little like the pointed remarks Farrell has dropped on his players after somewhat unpalatable results and performances.

“Jack, along with quite a few of our players, would have been hoping for better performance… some of them are lucky enough to get another chance to do that, others are coming in and some of them played pretty well themselves, but there were too many people not right at their best last week and we’re hoping for everyone to improve, not just Jack. Obviously, the control of the game is something that Jack would be open and honest about of wanting to step up a little bit this weekend, but we’ve certainly seen that in training this week.”

Whenever something goes wrong in a game, Farrell seems to be quite liberal when it comes to dropping names in enough places that the takeaway anyone listening has is that whoever he happens to mention seems to have a lot to answer for, but always with an “oh well, it’s more than just him” qualifier for deniability.

Like I said, maybe I’m too cynical.

Or maybe everyone else isn’t cynical enough.

For me, John Fogarty is like everyone else in this Irish set-up — completely reliant on what his head coach dictates. How much of a focus is the scrum in Ireland’s famous training system? How many sessions do they get in the weekly block of heavily limited on-field sessions? How much does the lineout get? There are only so many sessions. Only so much focus to go around. Anything you take from one unit has to be compensated for in another. It’s not like a club where you can layer focus across multiple training sessions across a week, month or seasonal block. You don’t get a test preseason where you can hothouse one area of the game over another for a time before changing focus.

So you’ll forgive me if my first port of call isn’t throwing a heap of blame on John Fogarty’s door after Saturday. He doesn’t pick the team, barely has a say in squad make-up, full stop. He works with the players and the time allotted to him and his unit, and just “has to make that work”.

So what happened on Saturday?

If you want an excuse for a scrum going badly, ask a prop. If you want the reason, ask a referee. What Matthew Carley saw on Saturday is far more important and far more instructive than anything Ireland can learn from the coiterie of ex-pros who will almost certainly be rolled out to tell us that up is down. South Africa can no doubt wheel out just as many ex-pros to dispute anything they might say, regardless.

For me, referees decide what a dominant scrum looks like. The scrums themselves just present the case for their decision. Sometimes you can gimmick that presentation by producing a picture of forward movement — with how that forward movement is achieved hidden behind the momentum — but to know what you should be doing, you need to know what the referees themselves are looking for.

They’re basically doing a very fast “crime-scene reconstruction” with their eyes: who started the problem?

1. Before the ball goes in: Shape and Intent

On “crouch, bind, set”, the ref is checking:

- Spine in line – no one already dipping or craning necks.

- Height match – one side not obviously lower to pre-load under the opposition.

- Angles – hips and shoulders square, not already pointing in or out.

- Binds

- Loosehead: long bind up the tighthead’s back/side, not on the arm or across the chest.

- Tighthead: bind on the body, not the neck/face.

Any team that’s already too low, twisted, or with short/illegal binds is on the ref’s mental “watch list” once the ball goes in.

2. At the hit & early shove: who changes the picture?

As they call “set”, the ref is looking for which side changes shape first:

- Sudden drop in height from one prop.

- One side driving across the scrum, not straight.

- Early shove before the ball is fed.

- Tighthead or loosehead stepping around to wheel.

This is important: modern refs are told to penalise the original offence, not just the team that ends up on the floor. So they’re trying to log, in real time, “who moved first and how?”

3. After the ball goes in – stability, angle, and bind

Once the 9 feeds, the referee’s key questions are:

- Is it stable?

- No sudden dips, pops, or “hinges” at the hips.

- Is everyone driving straight?

- No boring in (driving across the opponent) or walking around.

- Are the binds still legal?

- Hands stay on the back/side, not slipping to the arm, sleeve, or floor.

- Who caused the collapse/pop?

- Did someone pull down, angle up, or twist?

4. The loosehead’s elbow pointing down

For a legal loosehead picture:

- The loosehead takes a long bind up the tighthead’s back/side.

- Their outside elbow is generally up and out, roughly parallel to the ground.

- As they drive, their elbow doesn’t suddenly drop – their forearm stays “long” and connected to the tighthead’s back.

When a ref sees the loosehead’s elbow pointing down towards the ground, a few alarm bells ring:

- Shortening the bind

- Dropping the elbow usually means the loosehead has slipped from a long bind to a short one, onto the arm, sleeve or side of the jersey.

- A short bind makes it much easier to pull the tighthead down or twist him.

- Pulling down/hinging the scrum

- Elbow down + wrist turned in often means the loosehead is levering the tighthead’s arm and shoulder down, causing the tighthead to fold or hinge.

- If the scrum then dips or collapses on that side, the ref will usually penalise that side.

- Disguised angling

- A loosehead can also use the elbow-down position to crank their shoulder up and in, making it look like the tighthead is popping or losing height.

- From the ref’s angle, if the loosehead’s elbow has gone from horizontal to pointing at the grass and the tighthead suddenly buckles, the picture of illegality sits with the loosehead.

So, in short, a downward-pointing loosehead elbow is a big modern tell for:

- Short bind

- Pulling down

- Inducing a collapse/hinge

…and refs are absolutely trained to look for that before they decide the tighthead “just can’t handle the pressure”.

5. How they “stack” those pictures

When there’s a messy scrum and bodies on the deck, the ref’s internal checklist is roughly:

- Who changed height or angle first?

- Did anyone’s bind change (e.g. loosehead elbow drops, tighthead grabs arm)?

- Did that change immediately precede the collapse, wheel, or pop?

If the answer to “who changed first?” is “the loosehead – his elbow went down, bind shortened, then the scrum collapsed,” the penalty is almost always going that way, even if the tighthead is the one lying in a heap.

In a general sense, you’re going to see one or two of these show up in every scrum, to varying degrees based on when they happened and whether they’re a reaction to something else. If you’re a loosehead, for example, and the scrum dynamic moves forward or “up”, your bind might end up high on the tighthead’s shoulder, but, for the most part, you’ll be OK if you were mostly legal throughout.

Ireland’s problems with the scrum started early, both on the clock and on the set up for the first scrum.

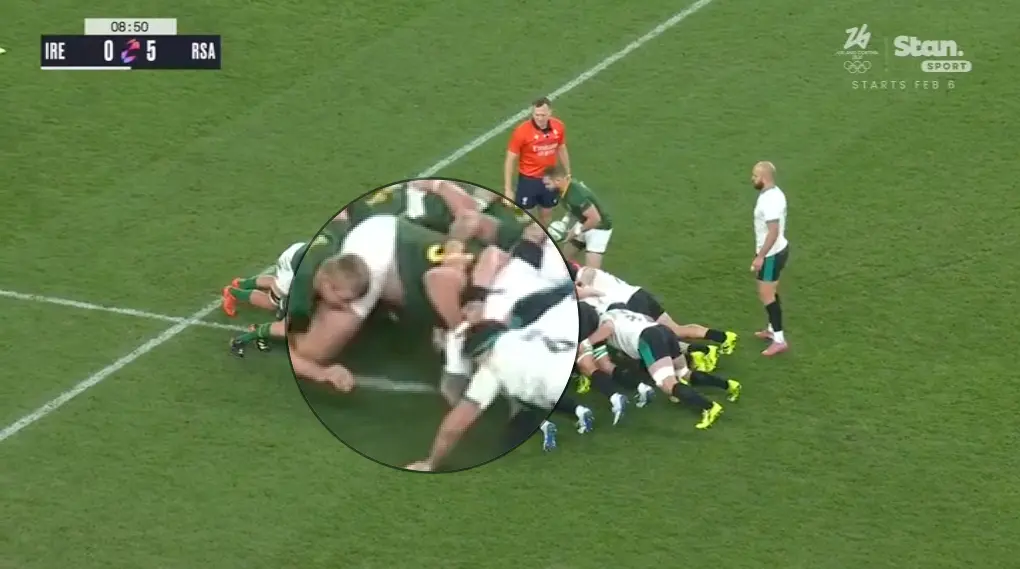

Here’s the first scrum of the game around the eight-minute mark.

Let’s go frame by frame. First, look at Porter’s outside leg and how far outside of Thomas Du Toit’s leg it is. I think there are two reasons for this.

- Porter is giving up around 3″ in height to Dan Sheehan, so to make sure they are square on the set, he kicks his left leg out to compensate.

- It gives him his natural “bore” angle inwards, which allows his second step after the set to explode his left side up into the tighthead’s chest.

If that initial step and thrust is against a smaller, weaker or technically inferior tighthead, it’s usually enough to blast them off their feet and weaken the left-handed belt-bind of the tighthead on his hooker, which opens up an easy seam directly onto the opposition hooker.

Here’s what that belt-bind looks like — it’s pretty standard across the game. It’s directional, mainly, and primarily locks all the shoulders across in a line, while still allowing the tighthead more freedom to move as the scrum settles in place.

Porter’s starting bind, naturally, puts him at an angle on entry. This wasn’t visible on his work as a tighthead, as his natural bind there would allow both shoulders on. It’s why, from a scrummaging perspective, Andrew Porter was so quickly promoted. He didn’t have to be the most technical scrummager on the field; his unbelievable strength brought him to the dance and kept him there.

That starting bind allows Porter to power up and through any tighthead who can’t hold him down, but it comes at a cost — his connection with Sheehan, and both of their stability as a result.

Porter tries to compensate for this by shortening his bind on the tighthead — especially tall tightheads who fill that space between him and Sheehan immediately on the set — and pulling down.

But against super-heavyweight tightheads — Du Toit is 135kg — that serves to pretzel Porter diagonally in, where he’s out of line with Sheehan, and thus out of balance with Sheehan. Sometimes, depending on the tighthead, this can be enough to pull both men down and either buy a reset — “both to ground” — or even a penalty if the AR or referee mistakes this starting point as the tighthead hinging.

For a guy like Du Toit, who is strong enough post-set to deny that, it puts Porter into an incredibly weak position where he can’t transfer any of his power through his legs and hips.

And that results in Du Toit driving through him – straight on vs side on is always a win for straight on. Live, I saw a few friends on WhatsApp calling this as Du Toit boring in but he’s not. It’s Porter’s natural starting angle and initial drop and pivot meeting a tighthead tall, strong and heavy enough to take that space between him and Sheehan on the set and then driving through that weak point.

It’s why almost all of the scrums that South Africa won a penalty on seemed to implode from the loosehead side on a diagonal through Porter, through Sheehan and then onto Ryan/Beirne as the game developed. The next sequence of scrums had Bundee Aki in as a flanker after Ryan’s red card, but the second row pairing of Baird and Beirne was a planned unit during the game, regardless.

With the context of the 8 v 7 included, large elements of what we’re talking about became more visible.

Elbow down, implode in and back.

Elbow down, impode in and back.

Elbow down, implode in and back.

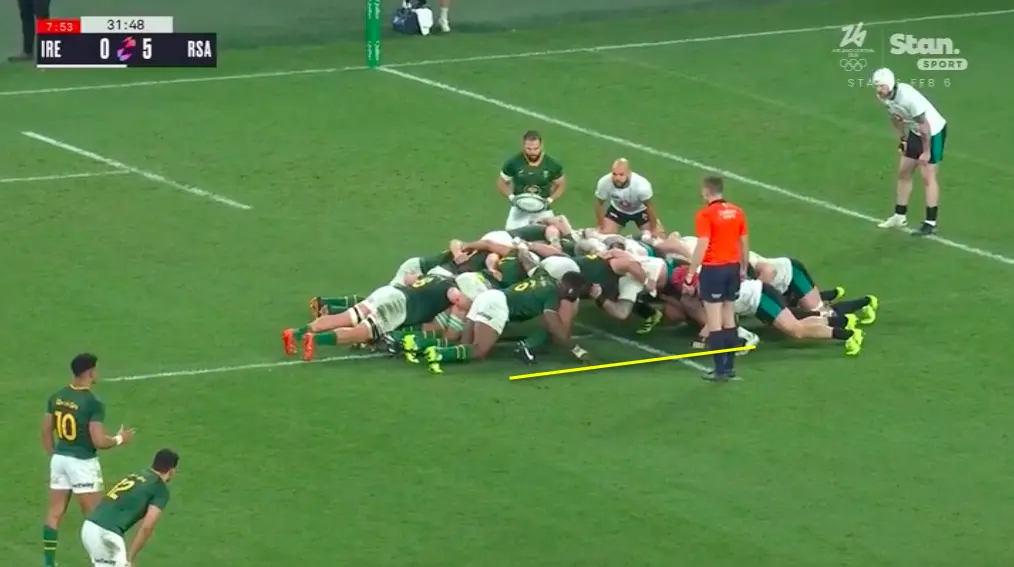

Interestingly, on one of the scrum resets in this sequence, Porter brought his outside leg back inside to give himself more stability. Let’s see what happened before Carley blew it up for a reset.

Look at Porter’s outside leg; it’s as close to straight on as you’ll see from him. Sure, it’s still splayed — that’s natural — and the elbow is still down, and he’s still losing height, but he has more straight-on resistance, but it has a side effect.

This is Porter reacting to the scrums that have come before and trying to prevent being cross-bored through.

But when his outside leg isn’t wide on the set, the height differential with Sheehan is exaggerated, and what does that produce? Sheehan getting popped on both sides, by Marx on his right shoulder and Du Toit on his left.

This continued on the next two scrum, leading up to the yellow card. Right before that scrum, Erasmus switched both his starting props out for Steenekamp and Louw. This is a pretty simple equation; both Venter and Du Toit are most effective as 40-minute options, so would have likely been switched out at halftime anyway, but with the scrum planted on the five metre line, it basically brought in two fresh super heavyweight scrummagers to power through Ireland’s already flagging and demoralised pack.

You can see Porter buckle on the set almost immediately.

He buckles down and diagonal again — something Siya Kolisi is quick to point out to the referee — and a yellow card at this point, warning or not, is long overdue.

Elbow down, implode in and back.

We never got a good look at what Boan Venter was doing to Furlong in all of these clips because those angles were never shown, but it’s clear from these that Furlong is getting shunted up and depowered on almost every shove which, again, exposes Sheehan to ferocious pressure coming through from Marx who is free to attack with Furlong, essentially, out of the equation.

After Porter’s yellow, Paddy McCarthy made his way onto the field and actually showed a pretty good picture from an elbow perspective. You’ll see here, even though he’s driven back at a rate of knots, he keeps his elbow parallel to the ground.

He loses this engagement, in tandem with Furlong on the other side, by getting too low underneath Louw and getting — essentially — squashed. McCarthy had tended to use this style for Leinster too, most notably against John Ryan and Ruan Dryer in the URC. He starts low, with his head below his hips and tries to bully through the tighthead.

That might work with two sub-120kg tightheads north of 35, but not with Wilco Louw, who is 145kg and 6’1″ — he’s too short to lever out, and too heavy to feasibly out-power when he wins the set.

McCarthy would later be yellow-carded for this exact thing as he kept getting trapped underneath Louw and getting landed on. For a heavyweight tighthead, this is essentially what you’re told to do — “land” your chest on the loosehead at an angle like the way a plane lands on a runway.

McCarthy couldn’t live with it technically or physically and offered very little protection to Sheehan from Marx or Louw.

Ireland’s scrum skittered backwards, and the long-overdue penalty card was awarded, although I don’t think it was for any one of the props more than another.

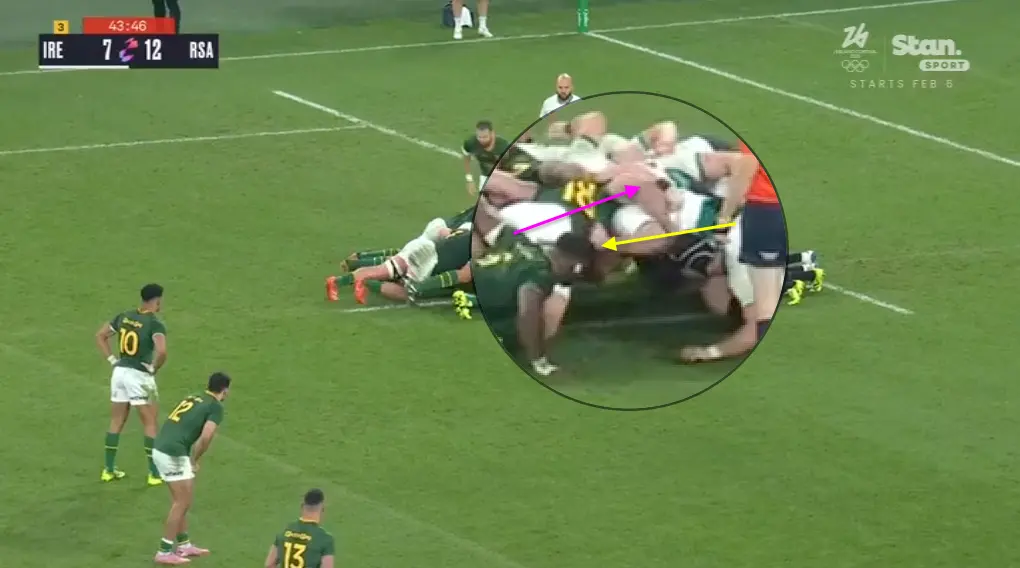

In the second half, we got a good look at how Boan Venter was scrummaging on Tadhg Furlong. Look at the differences.

One, Venter’s leg is pretty much square, certainly relative to what we saw from Porter. It’s comfortably inside Pieter Steph Du Toit’s planted arm.

Second, elbow up.

At this point, Marx is completely on top of Dan Sheehan.

This dominance is coming from the South African tighthead side — entirely legally, or as legally as you’re going to get at — and it’s exaggerating Sheehan’s big weakness; his height as a scrummager.

Sheehan’s bind on Furlong was constantly breaking under pressure. You can even see it on our put-in. Compare Sheehan’s bind on Furlong here with Marx’s on Louw.

That comes from the pressure Sheehan is feeling on his left shoulder. He’s trying to stay bound to McCarthy, but the pressure there is too much, so he has to pick a side, essentially.

At this point, we fully committed to trying to buy a free kick (either ours or theirs, where they wouldn’t be able to scrum on the next restart) by belly flopping on the tighthead side. First Furlong, and then Bealham.

Porter — back on the field post yellow card — tried kicking his leg out again on Sheehan’s last few scrums before being replaced to see if Furlong’s belly flop might empower him to get forward movement on Louw. They were trying to see if that might get Sheehan a chance to breathe against Marx, and it actually worked. It should have been a penalty against Furlong, but Carley instructed South Africa to use it.

A reprieve, of sorts. We then brought McCarthy back on, and the initial issue with McCarthy — head below his hips and getting crushed inwards — returned, ending in his yellow card.

This was the most visible example of the concept — loosehead collapsing for two different reasons, and Marx and Louw dominating the Irish hooker (Kelleher) diagonally in, and down.

So the question is this: is it systemic?

Will this repeat? With the same tighthead pressure, yes.

Porter’s issues weren’t just to do with Du Toit or Louw, and neither are McCarthy’s. In a situation where both can easily overpower their tighthead — like McCarthy was with Dreyer and Ryan — you won’t see it, but with any other team with a strong scrummaging hooker and super-heavyweight tighthead, this problem will show up over and over again without either a change in personnel or a change in coaching focus.