It’d be easy to fool yourself.

Comforting, even. I can feel the urge myself.

Ireland showed grit. Toughness. Heart. They never stepped back from a fight they were losing in almost every category.

They-

No.

These are distractions. Empty calories. They are 2008’s “soft landing”. They are committing to Dry January with the Christmas slab of cans still in the fridge.

Please make no mistake about it; we were absolutely pummelled in this game. The scoreboard doesn’t show that fully, in part because the Springboks were more concerned with humiliating us physically than actually converting their 22 entries, and in part because of some outstanding Irish red-zone defence. It was a beatdown. The fireworks and lights-out walkout pre-game had all the hallmarks of a heavyweight boxing match. If the same logic held, the referee would have waved it off at halftime. My big takeaway from this game was that the Springboks were true heavyweights, while we were punchy cruiserweights hoping that the usual rules of size and power — and the reality those rules enforce — could be suspended for just one night.

The Springboks beat us up. There is absolutely no shame in that, for me. It happens. We were absolutely annihilated in the scrum, but we’re far from the first side to come out on the wrong side of that against the Springboks, and we won’t be the last, either.

What matters now is our response.

By any metric, Ireland’s Pink Dress is frayed. Andy Farrell’s system, such as it is or was, is no longer fit for purpose against the very best.

Will it still beat Wales, Italy and probably Scotland? Yeah, probably. Will what we saw here translate to wins in Paris or Twickenham if nothing changes? I would say probably not. Would that mean a return to third in the Six Nations and maybe talking about how good a Triple Crown might be, like it’s 2003 all over again? Almost certainly, that is, until we play England as we are currently constructed.

Change is needed.

What does that change look like? That depends on whether you’re dealing with any other test coach or whether you’re dealing with Andy Farrell. We know what Farrell does. He doubles down on what he knows, and that is trying to get Leinster’s domestic and European dominance, whatever that looks like, to scale up to test level with a few holes filled from elsewhere.

This has wide-ranging effects. It is now negatively affecting Leinster, as it was always going to do eventually. Porter, Sheehan and others look like pale imitations of who they were even 12 months ago.

Perhaps all will be well when Leinster put away a feckless and inconsistent Harlequins side in a few weeks. But the Six Nations, never mind heavyweight battles with Bayonne and La Rochelle, are waiting. The Irish system was never designed to put so much weight on one province and, eventually, that has a cost with injured players, existensially exhausted players and bloated wage bills.

Something has to change, before it’s too late.

22 Entries & Points per Entry

Actual

- Entries: Ireland 6, South Africa 10

- PPE: Ireland 1.1, South Africa 2.4

KPI target

- SA ≤ 9 entries, Ireland ≥ 9

- Ireland ≥ 2.8–3.0 PPE, SA ≤ 2.2–2.4 PPE

Verdict

- Ireland were miles off: only 6 entries and 1.1 PPE is exactly the “do loads of work, get nothing” outcome I was worried about.

- The Boks were basically on their season template: 10 entries (just above the cap of 9 I hoped for in the Green Eye) and 2.4 PPE (right at the upper end of what I said Ireland could feasibly live with).

- Scoreboard tells the same story as the model: 10 × 2.4 ≈ 24, 6 × 1.1 ≈ 6–7 plus a bit, that’s a 24–13 type game.

KPI result:

Ireland failed both access and efficiency targets; South Africa hit theirs — game over almost before you look at anything else.

Linebreaks & Ruck Profile

Actual

- Rucks won: Ireland 93, SA 59

- Linebreaks: Ireland 3, SA 5

LBR:

- Ireland: 3 linebreaks on 93 rucks

- LBR = 3 ÷ 93 ≈ 0.0323 → 3.2 linebreaks per 100 rucks

- That’s one linebreak every ~31 rucks.

- South Africa: 5 linebreaks on 59 rucks

- LBR = 5 ÷ 59 ≈ 0.0847 → 8.5 linebreaks per 100 rucks

- About one linebreak every ~12 rucks.

- Ireland ≥ 8.5 LBR per 100, SA ≤ 8 per 100

Verdict

- Ireland only managed 3.2 linebreaks per 100 rucks — less than half of the target.

- South Africa were bang on their seasonal profile: 8.5 per 100, just above the limit I set in the KPIs (≤8).

- This is almost the textbook “Ireland carry and recycle, South Africa carry and break” game.

KPI result:

Ireland miss badly on their LBR KPI; SA are slightly above the ceiling we, ideally, wanted for them.

Kicking & Territory

Actual

- Total kicks: Ireland 29, SA 31

- K:P ratio: Ireland 1:5.1, SA 1:3.5

- Territory: Ireland 42%, SA 58%

- Possession: Ireland 50%, SA 50%

- Possession last 10’: Ireland 78%, 0 points

KPI target

- Force SA towards 1:5 or looser (play more from deep) through a rock-solid lineout, scrum or a slashing transition game — essentially show South Africa that kicking to us in any facet should be rationed.

- Ireland had to live around 1:4–1:5, kicking smart rather than feeding their lineout or transition runners. Some of this was bloated with the scramble in the South African 22 in the last ten minutes, but generally held for the second half as Ireland tried to play their way out of suffocating 22 pressure.

- Territory/entries to reflect at least par access, not a big SA edge.

Verdict

- South Africa sat bang in their sweet spot: 1:3.5 — they kick a lot, control territory (58%), and that feeds into the 10–6 entry split.

- Ireland at 1:5.1 were actually more pass-heavy than we wanted, while losing the territory battle. That’s the danger band I wrote about pre-game: lots of phase-play, not much field position, and low PPE.

- The last 10 minutes are the microcosm: 78% possession, 0 points — Ireland keep the ball, but can’t turn it into meaningful entries or breaks.

KPI result:

Kicking pattern favours South Africa, not Ireland. They won the territory template that Ireland had to disrupt to have a chance, and with possession being broadly similar across a Ball In Play time of 31.5 minutes.

Set Piece – Lineout & Scrum

Lineout

Actual

- Ireland: 73% (11 throws)

- SA: 86% (21 throws)

KPI target

- Hold SA ≤ 85% overall, ≤ 80% in Ireland’s 40m.

- Ireland lineout ≥ 90% overall, ≥ 85% in SA half.

Verdict

- Ireland at 73% were nowhere near the 90% target — that’s not top-end tier-1 accuracy.

- South Africa at 86%:

- Slightly above the 85% ceiling we aimed for.

- Importantly, they get 21 lineouts to Ireland’s 11 — they just had more bites at the cherry and more opportunities to get their platform moving, so being sub-90% didn’t produce anything worthwhile for Ireland.

- So Ireland don’t get the Boks into the true “broken lineout” band (<80%); SA sit in a solid if unspectacular zone and still generate twice the platform we managed.

Scrum

Actual

- Scrums: Ireland 4, SA 16

- Win % on own feed: both 100% (but…)

- Ireland conceded 9 scrum penalties, two props to the sin bin, and a penalty try at the scrum.

KPI target

- Keep total penalties ≤ 11, and specifically don’t give SA repeated set-piece entries or card pressure.

- No cards.

Verdict

- The scrum is an enormous strategic fail:

- South Africa had four times as many scrums and harvest penalties, cards, and a penalty try.

- Every one of those penalties either gives South Africa a 22 entry or relieves pressure or builds pressure on the Irish pack.

- It completely nukes the discipline and territory KPIs (see below).

KPI result:

Lineout: fail for Ireland, borderline/OK for SA.

Scrum: catastrophic fail — exactly the scenario the KPIs were designed to avoid.

Discipline & Cards

Actual

- Penalties conceded: Ireland 18, SA 13

- Cards: Ireland 4 yellow, 1 red; SA 1 yellow

KPI target

- ≤ 11 penalties.

- Zero yellow/red cards.

Verdict

- Ireland were 7 penalties over the ceiling.

- Five cards total, including a red and two scrum-related yellows, is about as far from the plan as possible.

- Each card amplifies the scrum issue and the entries/PPE issue — South Africa, with a power scrum and a numerical edge, is the nightmare we were worried about.

KPI result:

Massive fail on discipline. This is probably the single biggest structural reason the other KPIs fell over.

Scoreboard & Flow

- SA led for 81 minutes (94% of the game).

- Ireland never led, despite:

- More rucks (93–59),

- More carries (120–97),

- More passes (152–112).

That’s exactly the “high work, low reward” pattern we were trying to avoid: Ireland doing the volume, South Africa owning the value.

TL; DR

Against the KPIs we set:

Hit / close-ish

None, really. The closest we came was holding SA’s LBR to 8.5 per 100 (just above the 8 target) and keeping SA’s PPE to 2.4 rather than a 3+ horror show. But that’s scant consolation. If anything, South Africa let us off the hook in that period of the second half where we basically lived in our own 22 for 10 minutes.

Missed badly

Entries & PPE: 6 entries at 1.1 PPE vs SA 10 at 2.4.

LBR: Ireland 4.4 per 100 vs target ≥8.5.

Lineout: 73% vs required 90%; SA up at 86% with double the volume.

Kicking/territory: SA in their comfort band (1:3.5, 58% territory); Ireland stuck in a 1:5, territory-poor game.

Scrum & discipline: 9 scrum pens, PT, 18 total penalties, 5 cards.

Ireland basically walked into the exact game I was worried that we couldn’t afford — a territory-heavy, scrum-dominant, card-heavy game that suited South Africa down to the ground — and then failed on every key efficiency KPI: too few entries, not enough linebreaks, a malfunctioning lineout and a disastrous penalty count.

It’s possible to win the game with the scrum being a complete torture chamber for almost the entire 80 minutes — a puncher’s chance, essentially — but not with our transition being so poor, the contestable kicking game failing and our inability to win collisions consistently.

Ireland hit some of the process numbers we like — tempo, carry volume, turnovers — but we lost every “power” and “field” metric that matters against this iteration of South Africa: set-piece, territory, post-contact, penalties and, ultimately, entries and Points per Entry.

Ultimately, the man who has to own defeat this is Andy Farrell.

But to me, as of late, when it comes to Ireland, it seems like he likes renting out that ownership, especially during losses. As you might expect, post-game, he didn’t want to hear anything close to criticism, unless it was directed at players he’s more than comfortable criticising in public at this point in his tenure. His focus was on how brave Ireland were, and how proud he was of defending with 12 players at one point, which is fine. It was brave. It was tough. But nobody could ever accuse any Irish side of lacking that, and I certainly wouldn’t and won’t be here.

Of course they were fighting for their lives. Of course they were putting their bodies on the line. Of course it was inspiring watching Paddy McCarthy rip into the Springboks with the ball in hand, despite looking like he was scrummaging against Jupiter in the scrum. How could you not rate that?

How were you not out of your seat watching Jack Crowley do this two sets in a row when we were turned to cinders under the Springbok blowtorch?

These lads are scrapping for their country, but I won’t damn them with faint praise.

Sometimes it feels like Andy Farrell is the most powerful man in the IRFU, until Ireland lose — then he becomes a helpless bystander, no more responsible for the loss than the people supping pints or scrolling Instagram in the Aviva Stadium below him. There’s always someone else to pin it on. He just can’t win with these cats.

And then, when the heat gets too much, you have enablers in the media — pundits, ex-pros and journalists — talking about how bad things were for Irish Rugby in the 90s and, in a broader sense, about perspective. Look at how far we’ve come. Talking about fans getting “hysterical”. Little old Ireland. Sure, how could we be expected to compete with these lads? They’re massive.

We had no wifi in the ’90s either, but you best believe if it goes down tomorrow, you’d be on the phone after an hour trying to get it fixed.

We’re both perennially tied to being wooden spoon collectors back when John Bruton was Taoiseach, while also talking about how our “system” today is the envy of the world. We can’t have it both ways. Or maybe we can. We are, at once, one of the best sides in the world, but we also never have to take on the actual mantle of expectation that entails. We were the best side in the world in 2023, favourites for the World Cup, but when we lost to the All Blacks in a quarter-final — a side we’d beaten three out of four times during that cycle, including twice in New Zealand — we were more than happy to revert to We Lost But We Won. A walking contradiction.

After defeats, I often see the idea propagating that we simply don’t have the players to compete with the likes of France or South Africa, or, depending on the day, England. However, ask most people around the ground to name a World XV before the game, and it’d have Porter, Sheehan, Furlong, Beirne, Doris, and Van Der Flier in it. Some would have Gibson Park, Garry Ringrose, Ryan Baird, Mack Hansen and James Ryan. Some would consider Sam Prendergast and Tommy O’Brien amongst the most exciting players in Europe. This is what our rugby media tell us.

We don’t have the players multiplied by who would you drop — a contradiction.

Big Little Ireland. Never Out Of Form, Back In Form Ireland. Old New Ireland.

At a certain point, Andy Farrell is either a great coach, a fantastic selector, or he’s not. Maybe he’s something in between and, like the rest of us, trying to muddle along as best as possible, making mistakes along the way. Maybe we got the game plan wrong. Maybe it was too reliant on the scrum being a non-factor, or at least not a disaster, to kick as much as we did. Maybe the game against Australia gave us a bad read of where we were. Maybe it was all of these things.

But it’s far from an isolated incident.

What we saw here was visible against New Zealand in Chicago. Against Italy in the Six Nations. Against France. Against Wales. Against England for 60 minutes. Against Australia and Argentina last November in victory, and then against the All Blacks in defeat.

And it’s not getting better.

It’s getting worse.

There was a huge focus on the scrum in this game, and I’ll cover that in the GIF Room this week, but the biggest issue for me was how different the kicking game was this week compared to last week.

I’m not going to judge Ireland’s scrum — gimmick-led at the best of the time — against the best scrum in the game at the moment. Ireland didn’t set out to win the scrum battle. I think we wanted parity at the most and got way, way less than that, but our ultimate aim against any proper tier 1 side — top five, essentially — is for the scrum to be a non-factor.

The scrum, for Ireland, is a necessary evil that sometimes can turn into a strength against the lesser sides in the test game, or if we can find a favourable matchup for Andrew Porter, usually against a smaller tighthead, or one whose main strengths lie outside the set piece. If we can finesse parity through a mixture of walking around Andrew Porter or buying a few technical penalties with a mixture of carefully stage-managed tighthead belly flops, pulls or gap-closing. Sometimes we get away with it.

I would posit that our props and hookers are not primarily selected for their scrummaging, outside of Furlong, who, for me, is still the most complete tighthead on the island.

So I’ll judge Ireland on what we selected specifically to do — kick well, chase well, and win the territory and transition battle.

If the kicking game against Australia was the best possible outcome for our kicking strategy, this game was far closer to what you would expect from a first-class opponent. From a stylistic perspective, I think we knew that we couldn’t play through South Africa, so it was reasonable to expect, given our success in the air this season, that contestables and drop-transitions would be our way into the game.

That put a lot of pressure on Gibson Park and Prendergast to duplicate what we saw last week, as well as on our chasing unit. We brought in Ringrose for this, specifically, along with hoping that Hansen could duplicate his heroics from last week.

It didn’t work, at least not anywhere close to the same level. This selection of clips is a good example.

That’s far from the return we saw last week. South Africa kicking at distance, and our returns not reaching anywhere near the same level of outcome as last week’s game against Australia.

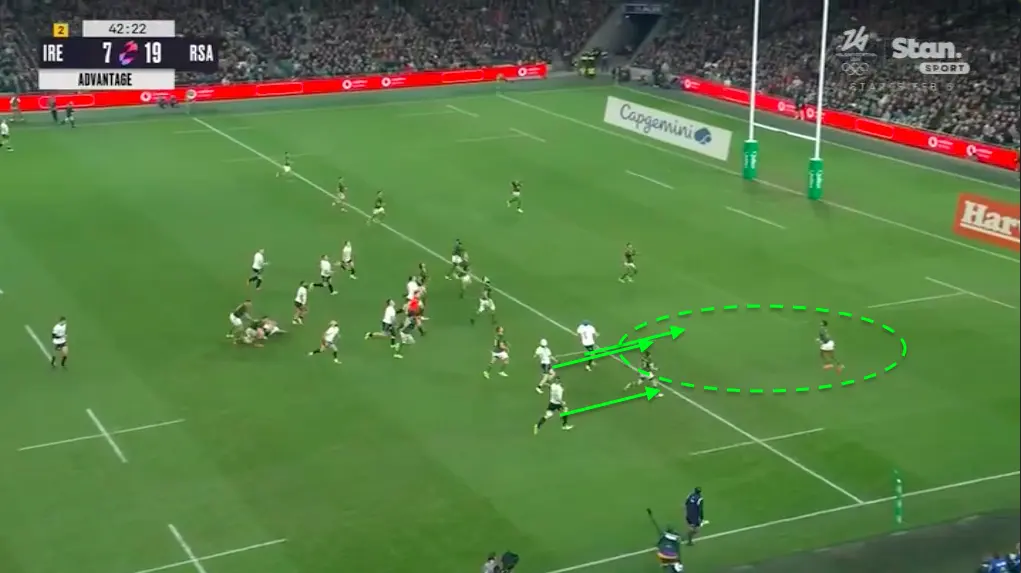

Our direct contestables seem to take an out-to-in profile as the game developed. Typically, box contestables tend to be made from inside the 15m tramline, to make for a straight kick up the line. These kicks usually have a lot of pressure on the outside of the chase — your transition defence shuts off the pass back inside — but you usually have only one or two primary chasers going up the 5m line with a forward, usually, chasing up from the infield side of the kick.

When you kick from a more central position — outside the 15m tramline — it’s normally a more difficult kick for the scrumhalf, but you can maximise the chase by having three or sometimes four chasers. Basically, someone chasing after the high ball, and then others sweep up behind for any breaking balls.

Even on these, we struggled to gain any dominance, while South Africa found a lot of purchase off theirs — both from #9 and #10, even without what I would call a dominant kicking performance. Here are some good examples.

That one from Gibson Park towards the end with Beirne chasing was a good example, even on penalty advantage.

You can see Beirne chasing, Hansen assisting, and Doris shooting up on the outside to mop up any pass (or break by South Africa) that might ensue.

As with most of our kicking here, it didn’t fall in our favour, even with the proviso that it was kicked on penalty advantage.

This was true on almost all of our kicks. As with Australia, let’s focus on the contestables. These were kicks that were designed to be chased, with the idea being that we could retain the ball on the drop, either directly with a catch, a bat back, or a South African knock-on. Where it got really interesting was when I included the scrum as a context piece to Ireland’s kicking.

What actually happened?

Outcomes by “who really wins”:

Clear Irish wins (2/9 – ~22%)

- Kick 1 – bat back, Ireland retain.

- Kick 3 – SA knock-on, Ireland scrum.

Neutral-to-bad for Ireland (7/9 – ~78%)

- Clean SA takes: Kicks 4, 5 (with mark), 8, 9 → SA ball with no real pressure.

- Penalty vs Ireland: Kick 2 → clean take and tackle-in-the-air penalty. Double loss.

- Technical error: Kick 6 → out on the full, SA lineout + territory.

- Bat back but lost: Kick 7 → initial Irish touch, ends up SA lineout.

So:

“Wins”: 2/9 (22%)

Direct negatives (penalty or out-on-full): 2/9 (22%)

Everything else: SA ball without Ireland gaining much.

Given Ireland’s usual contestable standard (around 19–20% regains, plus a lot of messy receptions), this is a poor yield because the “bad” column is so big: two big errors plus four clean takes and a mark.

How the scrum dominance warps the value of these kicks

In a normal game:

- Kick 3 (SA knock-on → Ireland scrum) is gold: you’ve flipped field position and kept the ball.

In this game:

- The scrum is a booby trap for Ireland:

- 9 scrum penalties against,

- 2 props in the bin,

- 1 penalty try.

- Almost constant pressure, regardless of who has the put in. Ireland had a 100% return from our three scrums, but every single one of those was going backwards.

That means any contestable outcome that turns into an Ireland scrum is only a theoretical win; practically, you’re:

- One handling error from giving SA a scrum instead, or

- One ref call from giving them another piggyback penalty and touchfinder.

So even our “good” contestable (Kick 3) feeds into the area of the game where South Africa are most dominant. It’s almost like the Boks can say: “Fine, we’ll live with the occasional knock-on – our scrum will get us out, or better.”

That has two knock-on effects:

1: Risk calculus for Ireland

Once the scrum starts going (first scrum on 8 minutes was a dominant South African penalty), every extra contestable bomb carries:

- The normal risk (penalty in the air, out on the full), plus

- The added risk that any messy regain is only one knock-on away from a lethal Bok scrum.

That helps explain why, despite 29 total kicks, only 9 were contestables — a far lower share than against Australia. The cost of a scrappy ball was that much higher.

2: Confidence for South Africa

SA can happily field more contestables near halfway, knowing:

- Clean takes give them easy exits or counter-kicks.

- Messy takes/knock-ons aren’t fatal because their scrum is a weapon, not a bailout.

Big picture on the contestable plan

Put together:

- Volume: only 9 contestables from 29 kicks – not nothing, but clearly toned down.

- Quality: 22% “wins”, 22% outright negatives, the rest SA ball with minimal disruption.

- Context: a dominant SA scrum and a solid SA lineout (86%) that turns most “neutral” outcomes into net wins for them over a few phases.

So the contestable game never really tilts the match:

- It doesn’t generate meaningful Irish 22 entries.

- The one “big” win (knock-on → scrum) points straight into South Africa’s strongest area.

- The worst outcomes (tackle-in-the-air pen, out-on-full) just hand them territory and platforms on top of that.

Ireland tried to keep the contestable kicking they’d used against Australia, but with South Africa’s scrum in full control, the risk/reward to that kicking flipped, and removed the effectiveness of Sam Prendergast at #10 almost immediately. Two wins from nine bombs and two big negatives is a bad trade at the best of times; when every knock-on feeds a dominant Bok scrum, the contestable game stops being a weapon and starts looking like another way to lose the field-position war.

Ireland’s usual retention rate this year has floated at around 19%, with a seasonal high against Australia (22%) .

Total Irish kicks: 29

Contestables: 9

“Wins” off contestables:

- Kick 1 – Ireland bat back & retain

- Kick 3 – SA knock on, Ireland get the scrum

Contestable retention

2 wins out of 9 contestables

→ ≈22% retention on the bombs themselves.

That’s roughly in the same ballpark as our usual contestable win rate, but with two really bad outcomes (penalty in the air + out on the full) dragging the value down.

Overall kicking retention

If we treat “retained” as “Ireland end up with the next structured possession (ruck or set-piece)” then:

- 2 retained out of 29 total kicks

→ ≈6.9% overall retention

That’s miles below the ~19–20% overall retention Ireland were running at in the Six Nations and Australia, and it’s why the kicking game never really shifted the contest:

- We didn’t contest as often (only 9/29 kicks), and

- When we did, only two of those produced genuine Irish possession, while the scrum dominance meant even the “win” that gave us a scrum wasn’t as valuable as usual.

This was Ireland’s main KPI — the one we selected specifically to activate — and it didn’t work. This was always the risk with this game plan. South Africa’s scrum dominance meant that contestables became a net negative for Ireland, when they were, for me, a core part of what we needed to do well to win.

South Africa had no such concerns and could kick to contest freely, as they had no fear of our transition as a direct attacking weapon. We just didn’t have the pace to hurt them, and when our scrum was such a liability as the game wore on, we started to kick longer because the fundamental problem hadn’t gone away. We could no run over South Africa, so when they kicked to us, we had to kick longer to escape the pressure.

They could contest freely, but we could not. So every kick became either a South African lineout that we couldn’t affect nearly as much as we needed to, and that, in turn, led to more defensive pressure.

That’s where the coaching staff need to examine their role in this. If we’re going to kick at this volume against physically dominant tier 1 opponents, we;

- Must have a better scrum because if we don’t, England and France will look to do the same thing that South Africa did here

- Become quicker and more incisive on transition, which requires changes at #10, #12, #13, #11 and #14, if Mack Hansen is going to stay at fullback in the longer term.

At the moment, we have neither, and it’ll affect us against elite teams and, for me, sub-elite teams who attack our lineout and kick at volume with anything close to decent high-fielding in their back field.

This is a pivotal moment for Andy Farrell and his coaches. Either we change, or Ireland’s status in the test game will change. It’s one or the other, at this point.

***

| Players | Rating |

|---|---|

| 1. Andrew Porter | ★ |

| 2. Dan Sheehan | ★★ |

| 3. Tadhg Furlong | ★★ |

| 4. James Ryan | ★ |

| 5. Tadhg Beirne | ★★ |

| 6. Ryan Baird | ★★★ |

| 7. Josh Van Der Flier | ★★ |

| 8. Caelan Doris | ★★★ |

| 9. Jamison Gibson Park | ★★ |

| 10. Sam Prendergast | ★★ |

| 11. James Lowe | ★★ |

| 12. Bundee Aki | ★★ |

| 13. Garry Ringrose | ★★ |

| 14. Tommy O'Brien | ★★ |

| 15. Mack Hansen | ★★★ |

| 16. Ronan Kelleher | ★★ |

| 17. Paddy McCarthy | ★★★ |

| 18. Finlay Bealham | ★ |

| 19. Cian Prendergast | ★★★ |

| 20. Jack Conan | ★★ |

| 21. Craig Casey | ★★★ |

| 22. Jack Crowley | ★★★ |

| 23. Tom Farrell | ★★ |

Some quick notes on this;

I rated Sam Prendergast as I did because the main thing he was selected to execute — the kicking game — didn’t function. His yellow card didn’t really factor into my rating at all, as it was a response to South Africa’s pressure. It was either him, or someone else. The two star part of his rating came from too many moments on the watchback where he either short-circuited under pressure, or left defensive responsibilities to others, such as when he drifted on Fienberg-Mgomezelu for South Africa’s try in the second half, leaving Gibson Park with way too much to cover on the inside, or when he just fell over next to a bouncing ball that I’d expect any other player to bust their hole trying to jump on. That needs to improve.

I did rate Jack Crowley down for his yellow card, in what was otherwise a fantastic defensive performance at fullback where he saved two, arguably three, tries from being scored.

Paddy McCarthy was, for me, the best player on the field from an Irish perspective once we factored out the scrum. He wasn’t just making tackles and forcing rips, he was winning collisions going forward and looked like our only threat with the ball in hand.

Craig Casey had a really strong impact off the bench, even though he only had eight minutes to work with. Tadhg Beirne had another tough game as part of a pack that was thoroughly beaten up. The lineout was better than previous games at this level, but came under heavy pressure. He’s found it difficult to get going this November.

James Ryan should have seen a straight red card for his ruck entry and, to be fair, I feel a card like that has been coming with him for a few years now. He is constantly shooting off his feet like that and he looked too focused on being an “enforcer” during his time on the field, which never seems to suit him in games like this, against teams like this.

Andrew Porter and Dan Sheehan have arguably had their worst November block for Ireland since they broke through to this level. Both players look physically and mentally drained.

Ryan Baird had a decent game for me, as did Caelan Doris, but only really on the defensive side of the ball. At a certain point, we need to see more physical output from both outside of their specific area of strength.