The European Cup is not what it once was.

Yet, because of the teams expected to compete at the top end of the tournament next May — Leinster, Toulouse, UBB, Bath/Northampton/Toulon — it remains a trophy worth winning because of who else wants it. It’s not the cultural engine it was in the 2000s, when it was arguably more compelling and tribal than test level most years, but it still has the juice.

In Ireland, seasons still revolve around it for most fans. The URC isn’t quite “the league” it was in the 2000s and 2010s, but how you do in Europe still defines a successful or unsuccessful season. Leinster, for example, are built to win Europe. Their URC title last season was… nice, but they are defined by whether they end the season with a star. Toulouse and UBB are slightly different, given the history of the TOP14, but UBB’s season last year was considered a massive success because they ended it with a star on their European kit. Toulouse will wear their six stars this week with real pride.

Because it means something.

For Munster, the search for a third goes on.

Will we be successful in that regard this season? Probably not, but you could argue that we’re as well poised as we have been in five or more seasons to have a real crack at it. For me, we’ve gone from “no chance” to “who knows” in the space of a preseason, thanks to the impact of Clayton McMillan, but we’re still one or two players away from being genuine contenders. Reaching a semi-final this year would be immense, but we need momentum and a run of home knockouts to do it. The beauty of Munster Rugby is that you never quite know. Odds, however impossible, often run into the hurricane of the Brave and the Faithful, and find themselves in a world where up is down and black is white. Or red.

There’s no better place to test the strength of the wind this weekend, away to Bath in the Rec. Bath, for me, are in the realm of genuine contenders this year. If Northampton were last season, then Bath certainly are this season.

Prem champions, Challenge Cup winners, star names everywhere and a budget to match. Van Graan has done what he almost always does: build an excellent squad and, untethered by the Irish system under Nucifora, he has built a serious unit at Bath that will be chasing for a bigger double this season.

Finn Russell at #10. Thomas du Toit. Sam Underhill. Guy Pepper. Harry Arundel. Ollie Lawrence. Santiago Carreras. Ted Hill.

Everywhere you look, Bath have quality.

Last weekend, Van Graan was in Ireland to watch the Stormers beat Munster in Thomond Park in the same way that he will expect his Bath side to do. Lots of kicking, big scrum, big set piece, quality on transition. For Munster, in a way, the Stormers were the perfect system check before this one, but Van Graan will be thinking the same.

Injuries post-Stormers mean that Munster will be approaching this one like the Hard Way it is — and always was, regardless — but I would posit that the game won’t be won or lost at #10 one way or the other; this is about the areas of the game that are left once you scratch off the areas where both sides nullify each other.

Nothing has changed about the core challenge here.

We will need to front up physically and look to stymie Bath in the core areas that make their game run. Van Graan has built a system at Bath that does that by default, regardless of who they play, so the terms are set.

Bath vs the Big Red Machine.

Munster Rugby: 15. Shane Daly; 14. Diarmuid Kilgallen, 13. Tom Farrell, 12. Dan Kelly, 11. Thaakir Abrahams; 10. JJ Hanrahan, 9. Craig Casey; 1. Michael Milne, 2. Diarmuid Barron, 3. John Ryan; 4. Jean Kleyn, 5. Tom Ahern; 6. Tadhg Beirne (C), 7. John Hodnett, 8. Gavin Coombes.

Replacements: 16. Lee Barron, 17. Jeremy Loughman, 18. Michael Ala’alatoa, 19. Edwin Edogbo, 20. Ruadhán Quinn, 21. Ethan Coughlan, 22. Alex Nankivell, 23. Alex Kendellen

Bath Rugby: 15. Tom De Glanville; 14. Joe Cokingasinga, 13. Max Ojomoh, 12. Cameron Redpath, 11. Henry Arundell; 10. Finn Russell, 9. Ben Spencer (c); 1. Beno Obano, 2. Tom Dunn, 3. Will Stuart; 4. Quinn Roux, 5. Charlie Ewels; 6. Josh Bayliss, 7. Guy Pepper, 8. Miles Reid

Replacements: 16. Kepu Tuipulotu, 17. Francois van Wyk, 18. Thomas du Toit, 19. Ross Molony, 20. Ted Hill, 21. Tom Carr-Smith, 22. Santi Carreras, 23. Sam Underhill

It’s not unreasonable to say that Bath are the evolved version of what Van Graan would have done at Munster had he the free hand in recruitment that he has now. Van Graan’s system, such as it is, is often derided as kick-heavy non-rugby, but it looked that way at Munster because he rarely had the squad that would have worked fully.

He wanted a top-end tighthead for years — he tried to sign one in 2019 and pivoted to De Allende once that was denied and the money was still available after making two semi-finals in a row between 2016/17 and 2017/18.

At Bath, he got his man, Thomas Du Toit, to pair with Will Stuart. They are the primary anchors for Van Graan’s game. Van Graan loves to load his team with heavy props, heavy locks and lineout specialists and transition specialists, so he signed the likes of Franco Van Wyk, Quinn Roux, Jacque Du Plessis, Ross Molony, Finn Russell, and Henry Arundell, while taking punts on guys like Regan Grace, as well as adding talents like Ted Hill and Guy Pepper from distressed English Prem clubs.

He is a squad builder, at heart, and he has built a serious squad at Bath that perfectly reflects his core fundamentals.

His teams want to kick, yes, but with a purpose. He wants guys who specialise in transition — Russell, Arundell, Carreras — and he wants a scrumhalf that can kick accurately — Will Spencer — and he wants his forwards to block off everything that comes from those two states; dominant scrum, dominant lineout.

And they are incredibly formidable.

However.

Looking at their numbers so far this season, Bath comes into this game looking like a classic “kick to control entries” side. They’re winning games by getting to the 22 more often than their opponents and being a little bit sharper once they arrive, but there are some real cracks that we can lean on.

Bath’s six-game PREM profile – what are they, really?

Results:

- Played 6: W5, L1

- Total score: Bath 209 – 130 Opponents

→ about 35–22 on average, a +13 margin per game.

22 Entries & Points per Entry

Across the six:

- Bath 22 entries: 71 → 11.8 per game

- Opposition 22 entries: 50 → 8.3 per game

- Entry differential: +3.5 entries per game

Using the actual scoreline:

- Bath PPE: 209 ÷ 71 ≈ 2.9 points per entry

- Opp PPE: 130 ÷ 50 = 2.6 points per entry

Try conversion:

- Bath: 30 tries from 71 entries → 42% of entries become tries

- Opposition: 18 tries from 50 entries → 36% of entries become tries

So the core of Bath’s game is:

- Volume of chances: +3.5 entries per game that they generate through kicking, transition and set piece dominance.

- A small but real edge in conversion: 2.9 vs 2.6 PPE, 42% vs 36% try rate.

They’re not freakishly efficient; they get to the 22 more often than their opponents, and are slightly sharper once they’re in.

The one loss (Leicester) is also the only game where:

- They lose the entry count (8 vs 9), and

- Their set-piece collapses (more on that below).

Rucks, linebreaks & LBR

Totals:

- Bath rucks: 583 → 97.2 per game

- Opposition rucks: 439 → 73.2 per game — PREM teams have been kicking back a lot of Bath’s kick volume, something that has empowered Arundell, in particular, to kill teams on transition.

- Bath linebreaks: 49 → 8.2 per game

- Opposition linebreaks: 35 → 5.8 per game

Converted:

Bath LBR:

- 49 ÷ 583 ≈ 0.084 → 8.4 linebreaks per 100 rucks

- ≈ one linebreak every 11–12 rucks

LBR conceded:

- 35 ÷ 439 ≈ 0.080 → 8.0 linebreaks per 100 rucks

- ≈ one linebreak conceded every 12–13 rucks

They carry a small linebreak advantage, not a massive one. The bigger story is in volume:

- Bath average ~97 rucks per game,

- Opponents ~73 rucks.

Rucks per entry:

- Bath: 583 rucks / 71 entries ≈ 8.2 rucks per entry

- Opposition: 439 / 50 ≈ 8.8 rucks per entry

Bath reach the 22 faster from the same ruck count than their opponents. That’s their “system” essentially — they’re a well-drilled kicking side that turns their possession into territory and entries more efficiently, through their set piece and efficiency in transition.

Game shapes:

- Quins & Saracens: both sides have high LBR; Bath are happy in open, high-event games.

- Sale: opposition at 0 linebreaks – their best defensive LBR outing.

- Leicester: Bath’s LBR spikes (8 linebreaks on 66 rucks), but they still lose because platform and entries go against them.

Key Takeaway: Bath are comfortable in games with lots of events and linebreaks, but their real edge is that they own more rucks in the right areas more often than not, and turn those into entries.

Lineout & scrum – where it creaks

Lineouts:

- Bath lineouts: 88 → 14.7 per game

- Opposition lineouts: 91 → 15.2 per game

Weighted success:

- Bath: 74.1 wins from 88 throws ≈ 84.2%

- Opposition: 77.06 from 91 ≈ 84.7%

So Bath are fine, not dominant. The detail matters:

Bath by game (own throw):

- Quins: 12 lineouts @ 67%

- Sale: 13 @ 85%

- Gloucester: 12 @ 92%

- Leicester: 13 @ 69%

- Bristol: 18 @ 100%

- Saracens: 20 @ 85%

This is a swingy lineout:

- Two poor days in the high-60s (Quins, Leicester),

- One perfect day (Bristol),

- Three good days (85–92%).

Over the block, the opposition actually throw more lineouts at a slightly better percentage.

Scrum (Leicester game note):

- Bath had 10 scrums and only retained 44%.

- That’s a genuine collapse, not just a bad 5-minute patch.

And — crucially — that’s the only game they lose.

So there’s a clear pattern:

When Bath’s lineout and scrum are in the 85–100% comfort zone, their phase game and entry machine roll.

When those foundations crack — as at Leicester (69% lineout, 44% scrum) — the whole model shudders and the scoreboard comes back to the pack.

Kick-to-pass & territory

Bath kick-to-pass (passes per kick):

- Quins: 1:5.1

- Sale: 1:2.3

- Gloucester: 1:3.8

- Leicester: 1:3.2

- Bristol: 1:5.0

- Saracens: 1:2.5

Average ≈ 1:3.65.

Opponents:

- 1:5.6, 1:1.8, 1:5.1, 1:5.6, 1:3.5, 1:4.3 → average ≈ 1:4.3.

So Bath:

- Kick more often per pass than their opposition across the block.

- Aren’t “ball in hand only” – they use the boot as part of their possession and territory loop.

Template:

- Work through long-ish ruck chains (~97 rucks a game).

- Kick from a structured shape with a set chase.

- Generate lineouts, scrums and pressured receptions in the opposition half.

- Turn those into more rucks and, ultimately, more entries.

If the opposition lose that contestable/exit battle, they’re effectively feeding Bath’s:

- Ruck volume,

- Lineout volume,

- Entry differential.

Ultimately, Bath are about territory as empowered by their kicking game — more on that later.

So what is Bath’s model?

Putting it together:

- Scoreboard: ~35–22 per game.

- Entries: 11.8 vs 8.3 → +3.5 per game.

- PPE: 2.9 vs 2.6.

- Try conversion: 42% vs 36%.

- Rucks: 97 vs 73.

- LBR: 8.4 vs 8.0 per 100 rucks – a small linebreak edge, likely empowered by the opposition’s read on Bath’s own kicking game.

- Lineout: ~84%, swingy, not dominant.

- Scrum: Generally fine, but with a Leicester-level failure case.

TL; DR

Bath are a kick-savvy side that wins by stacking more rucks in the right areas, turning those into 3–4 extra 22 entries, and being just that bit more efficient with those entries than their opponents are.

When their set-piece is on, the machine hums. When the lineout and scrum are rattled together — Leicester away — the machine coughs and a very normal game breaks out.

That’s the true shape of Bath on these six games: dangerous, well-organised and happy in high-event rugby, but structurally vulnerable if you can turn the night into a set-piece test and flatten their entry differential.

Kicking To Dominate Space

Bath’s kicking volume and kick-to-pass ratio really interested me because their ruck volume is relatively high for a kick-pressure, counter-transition team.

So I compared all of their territory maps from the PREM campaign so far and came up with this;

Big picture – where Bath actually live on the pitch

Averaging the six games:

Bath with the ball

- ~8% in their own 22

- 23% in their own 22–half

- 32% in opposition half outside the 22

- 37% in the opposition 22

Opponents with the ball

- ~14% in their own 22

- 30% in their own 22–half

- 34% in Bath’s half outside the 22

- 23% in Bath’s 22

So Bath spend about 70% of their possession in the opposition half, and 37% of it in the red-zone, while opponents only get 56% in Bath’s half and 23% in Bath’s 22.

That dovetails perfectly with our 22 data: 11.8 entries vs 8.3 and a small PPE edge. Bath’s whole model is a territory machine that keeps them out of their own 22 and camped in yours. If you exit to touch, their lineout success hems you in place; if you kick to grass, they try to kill you with Russell, Cokinasinga, Arundell, and Carreras.

Game-by-game: how territory, kicking, and lineout interact

Quins v Bath (31–47)

- Territory: Bath again live in the red zone – 44% of their possession in Quins’ 22, only 2% in their own. Quins are much more evenly spread.

- Kicking: Another very pass-heavy game (1:5.1).

- Lineout: Bath only 67% on their own throw.

Read: Even with a bad lineout, Bath still camped in Quins’ 22 if the game opens up. Their phase play, kick returns and turnover-to-attack are good enough that they can dominate territory without winning every lineout. The kicking is low because they’re already living in good zones — they don’t need to kick to move the game. That came back to Quin’s profligacy in that game.

Bath v Sale (28–16)

- Territory: Bath have 47% of possession in Sale’s 22; Sale have just 9% in Bath’s 22 but a lot in the “no-man’s land” in Bath’s half (35% + 42% in the middle bands).

- Kicking: Bath were much more kick-happy (1:2.3 – lots of kicks relative to passes).

- Lineout: Bath at 85%, Sale at 76%.

Read: This is Bath using a kicking + lineout template. They’re happy to trade kicks, push Sale back, then trust a strong lineout to turn territorial gains into set-piece starters. Sale see plenty of the ball in Bath’s half, but almost none inside the 22 because Bath’s exits + contestables and lineout defence keep shunting them back out.

Bath v Gloucester (38–17)

- Territory: Bath have 39% in Gloucester’s 22, Gloucester 21% in Bath’s. Middle-third numbers are quite similar.

- Kicking: Moderate, mixed game (1:3.8).

- Lineout: Bath 92%, Gloucester 86%.

Read: This is Bath with a high-functioning lineout and a balanced kicking game relative to their template. Entries are fairly even (12–11), but Bath use their set-piece and red-zone territory to score more efficiently (2.9 PPE vs 1.5). They don’t need huge entry volume if their lineout is clean and their 22 work is accurate.

Leicester v Bath (22–20) – the loss

- Territory: Bath spend 43% of their possession in the middle third, but only 12% in Leicester’s 22. Leicester are at 21% in Bath’s 22.

- Kicking: Bath are in the middle of their range (1:3.2).

- Lineout: Bath only 69%.

- Scrum: Bath retain 44% of their own scrums.

Read: This is what Bath look like when the platform collapses. They’re not pinned in their own 22 (only 12% there), but they get stuck between the 22s — lots of midfield possession, very little time spent actually camped in Leicester’s 22. Poor lineout and a battered scrum mean they can’t turn territory into repeat starters, and the whole entry machine flattens (8 entries vs Leicester’s 9).

Bath v Bristol (40–15)

- Territory: Bath have 49% of their possession in Bristol’s 22 and only 5% in their own. Bristol are at 31% in Bath’s 22.

- Kicking: Bath very pass-heavy here by their own standards (1:5 – few kicks, lots of phase ball).

- Lineout: Bath 18/18 (100%).

Read: This is Bath’s “dream” template — rock-solid lineout, barely any time in their own 22, and half their ball in your red zone. They don’t need to kick much because the set-piece gives them repeat field position, and they can stay on-ball there.

Saracens v Bath (29–36)

- Territory: Near parity. Bath have 30% of their ball in Saracens’ 22; Saracens have 25% in Bath’s. Both live a lot in the middle (32–34% bands).

- Kicking: Bath are quite kick-heavy again (1:2.5).

- Lineout: Bath 85%, Saracens 86%.

Read: Against top-end opposition who can match their kicking and set-piece, Bath’s territory advantage shrinks to almost nothing, and the game becomes a high-event shootout. They still edge the entries (13–11) and scoreboard, but they’re not suffocating Sarries the way they suffocate Bristol or Sale.

Patterns that jump out

They almost never live in their own 22.

- Only 8% of their possession is there on average, and in some games, it’s basically zero (2–5%).

- Their exit + kicking structure is good enough that once they get out, they hardly come back.

The Bath “kill zone” is sustained time in your 22.

- In their four big wins (Quins, Sale, Gloucester, Bristol), they live around 39–49% of their possession in the opposition 22.

- That’s where the 11.8 vs 8.3 entries and 42% try conversion are built.

There are two ways they get there:

- High set-piece + lower kicking volume – Bristol and Gloucester: strong lineout, fewer kicks, lots of phase ball in good zones.

- Kicking template + solid lineout – Sale and Saracens: more kicks, good lineout, use the boot to win territory, then cash it in off the set-piece.

- The Quins game shows a third flavour: even when the lineout is poor (67%), if the game breaks open, they can still camp in your 22 off phase and turnover ball.

When the set-piece is rattled, their territory doesn’t turn into entries.

- Leicester is the standout: midfield dominance on the map (43% there) but only 12% in Leicester’s 22 because lineout 69% and scrum 44% never let them stack starters.

- That’s the only game where the entry differential is against them.

Good teams can blunt the territory advantage.

- Saracens keep the maps almost symmetrical and still give up 36 points — Bath don’t need huge red-zone occupancy to hurt you if entries and LBR are high.

- But the “Bristol/Quins/Sale” extreme pictures — half the game in your 22 — are where Bath look utterly dominant.

In short, the maps confirm that Bath are a territory and platform side first, with the kick game and lineout feeding a model where they spend a ridiculous amount of time in your 22. The one crack that keeps reappearing is set-piece stress — when the lineout (and especially the scrum) doesn’t go their way, all that midfield possession stops turning into the terrifying “49% in your 22” picture and starts looking like just another arm-wrestle between the 22s.

This is what teams are trying to achieve by kicking to Bath at volume, but only Saracens and Leicester managed it, albeit with different outcomes and a few different levers being pulled.

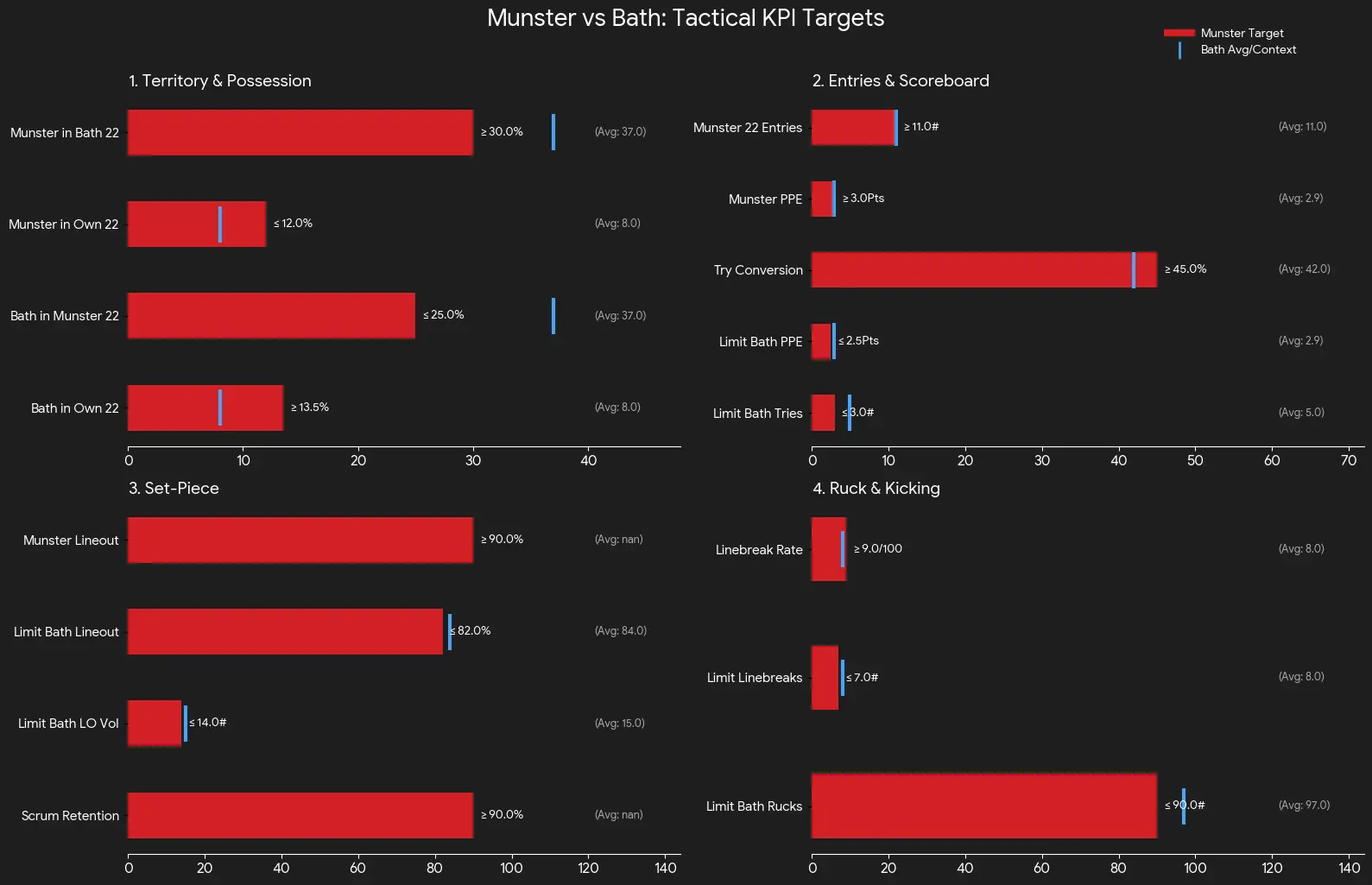

Munster KPIs

So, how do we go about upsetting this particular apple cart? It’s easier said than done, that’s for sure. But it’s far from impossible, especially with what we’ve shown so far this season, even against the Stormers.

Territory & Possession KPIs

With the ball (Munster)

Time in Bath’s 22

- ≥ 30% of our possession in Bath’s 22.

- Bath normally sit at ~37% in the opposition 22; getting to 30% keeps us in the same neighbourhood.

Time in our own 22

- ≤ 12% of our possession in our own 22.

- That’s slightly worse than Bath’s “never here” average (8%), but miles better than what most Prem sides manage against them. They will kick to us at volume; we have to threaten them with potential ball-in-hand escapes, but we should mostly look to exit after one or two rucks.

Without ball (Bath in possession)

Bath in our 22

- Bath ≤ 25% of their possession in our 22.

- A big win versus their usual 37%. If we hit this, their 11–12 entry norm is already dented.

Bath in their own 22

- Bath ≥ 12–15% of possession in their own 22.

- They normally live at 8% there; forcing more repeat exits and pressured sequences is a genuine structural change for them. This means kicking more of our possession around the 10m line to touch and between their 22 — little dagger grubbers along the ground — make them exit, pressure their four-man lineout.

Entries & Scoreboard

22 Entries For

- Munster ≥ 11 entries into Bath’s 22.

- That’s matching their average entry volume rather than letting them sit at +3.5.

Entry Differential

- Entry count at least level (Bath no more than +1).

- Their whole model is +3.5 entries per game; flatten this, and a lot of their edges vanish.

Points per Entry (PPE) For

- PPE ≥ 3.0. We have to be efficient here — we won’t win without it.

- Bath run at 2.9 — if we beat that, equal entries should mean scoreboard advantage.

Try Conversion in the 22

- ≥ 45% of entries becoming tries.

- Bath sit at ~42%; we want to be more ruthless with slightly fewer opportunities.

Bath PPE & Tries

- Bath PPE ≤ 2.5 and ≤ 3 tries conceded. This isn’t as simple as “score more than Bath” because

- Their norm is 2.9 PPE, and 5 tries a game; dragging them under these bands means their territory isn’t converting.

Set-Piece → Territory KPIs

Munster Lineout

- ≥ 90% on our own throw.

- No cheap Bath entries from overthrows or timing errors.

Bath Lineout

- Bath ≤ 82% on their throw, with at least 3 messy/turnover lineouts. Our selection directly reflects this. We need to get into their throwing lanes and spoil, even at the risk of burning out forwards to do it. A counter-lift on every single throw in the first 60 minutes with Ahern and Beirne.

- That drags them off their 84% average and towards the Quins/Leicester wobble days (high-60s/low-70s) that killed their territory-to-entry conversion.

Bath Lineout Volume

- Bath ≤ 14 lineouts total, and ≤ 8 in our half.

- They’re used to ~15 per game; keeping that down limits the number of “free” red- and amber-zone starts they get off their kicking game, so a lot of our kicks have to be coming down on their back three and midfield. Kick to contest anywhere near our 22, kick to touch if we’re pinned, and then contest.

Scrum Pressure

- Munster ≥ 90% retention, plus 2+ penalties/clear wins on Bath ball. This is the biggest ask.

- We don’t need a full Leicester-style 44% car-crash, but visible dominance or even parity here stops them settling into their exit and launch patterns, which will allow us to kick more freely. This is the clear pinch point for us, as our scrum has been a visible weak point in the last few games. We have to hit early and keep Du Toit off his stride.

Ruck, Linebreak & Kicking KPIs

Linebreak Rate with Ball

- ≥ 9 linebreaks per 100 rucks (≈ 7–8 breaks if we’re around 80–90 rucks).

- Bath concede about 8 per 100; 9+ means we’re punching above their usual leak, and we’ve hit that marker a fair bit ourselves.

Linebreaks Conceded

- Bath ≤ 7 linebreaks total

(or ≤ 8 per 100 rucks if they rack up big volume). - They normally sit at 8.0 per 100; keep them at or under that, which we have consistently done all season to teams like Leinster and the Stormers. If we can match that and win the aerial battle, we’ll be most of the way there.

Ruck Volume Balance

- Bath ≤ 90 rucks, Munster within ±5 rucks of their total.

- Don’t give them the 97 vs 73 split they enjoy in the Prem; keep the game’s total “event count” closer to our comfort zone. This is important because it reflects the balance of effort — we will want to make sure we get Beirne, Hodnett, Coombes and the likes of Edogbo, Quinn and Kendellen off the bench over their ball when they do look to play. High risk, but we have the best pure jackal in the sport and a good, visible reputation in this area of the game.

Contestables & Exits

- Net positive on contestables (regains + forced poor exits ≥ clean Bath takes).

- No more than 2 “bad exits” (out on the full/charged/straight to unpressured back three).

- This is the practical route to hitting the territory bands above — a sloppy exit here is usually another Bath lineout and another chunk of their usual 37% in our 22.

If we’re broadly in these bands — especially Bath ≤ 25% of possession in our 22, ≤ 10 entries, their lineout dragged into the low-80s, and ruck volume kept roughly level — we’ve broken the territory and platform pattern that’s powered their Premiership form and dragged them into our kind of game.

Then it comes down to whether or not we can execute when we get the opportunity. Bath aren’t a lockdown defensive side by any means, so we can hurt them, but getting to that point is the sticking point.

Then it comes back to the scrum; can we stay around 90% ourselves? Can we keep their scrum from generating 3+ penalties? If so, we’ll have a real chance of a losing bonus point, at least, which would be a great result from where I’m looking right now.