This great Irish team are on the decline.

That doesn’t mean they aren’t capable of great performances, or that their race is fatally run, but the peak that we saw from this side between late 2021 and 2023 seems to be over.

When you go looking for a headline to explain this dour loss, which looked like the kind of defeat we regularly suffered to the All Blacks pre-2016, that’s as good a general reason as any. It happens to all the great sides eventually. An inherent tiredness, staleness, and a kind of incremental boredom — more on that later — has taken down better sides than this one, so it shouldn’t be a surprise. It’s natural, but in the Irish system, it seems to be more mechanical than elsewhere. Our system builds to a peak, doubles down on it, and then inevitably rides it to the slide that always comes.

2000, 2007, 2013, 2020, and very soon — 2026.

This isn’t an obituary, by any means, but it is a signpost.

The first thing to say is that this team isn’t undercooked. Most of these guys need less rugby, not more. At this point in their cycle, the less rugby they have, the better as far as I’m concerned. This is a team that should thrive on freshness, not a week-to-week grind. However, if you’re looking for a hand-wave to explain why we lost to an All Blacks team playing as badly as they have all season, maybe being “undercooked” will suffice. It sounds good.

For me, Ireland didn’t play like a team that was undercooked.

The idea that Ireland would have been incrementally better here if they — the Leinster players that everyone is referring to when they talk about Ireland being “undercooked” — had played a game against a Sharks side that would have needed two full ass transplants to even gesture at improving on the half-assed performance they showed in the Aviva, or against Zebre if the schedule had allowed, is laughable.

To me, anyway. Your mileage may vary.

The answers for me lie in more fundamental truths. This team is slowing down, dipping a few percentage points from their very best, but these are subjective things. Hard to measure.

Ireland lost this game because of things we can measure objectively.

***

I didn’t order crow, but I had to eat a few bites on Sunday morning, all the same, as I was texting a friend of mine in New Zealand rugby.

“Three in a row.”

I had to take it on the chin.

He had a take.

I think it’s an interesting one. So I’m going to paraphrase it for you from a voice note.

He thinks that, if it weren’t for the timing of the 2017 Lions tour, the All Blacks would have won three World Cups back to back. Why? Because the Lions tour fell two seasons after the 2015 World Cup and, as a result, extended the life-cycle of that All Blacks side beyond the point it would have naturally ended. The coaching group wanted a winning Lions series to top off the run since 2007 that marked out that All Blacks side as the best test side to ever play this sport. So they relied on senior guys or players who were of a certain era of the sport — suited the game that was, not what would follow — a little too long. They didn’t freshen up core areas. It wasn’t about icing some guys out, although that would have happened in some spots — it was about the opportunities they didn’t give, the chances they didn’t take, the doors they didn’t even look at, never mind open and peek through.

That Lions series ended in a draw — seen as a loss in New Zealand — so it was all for nothing, anyway, but he thinks that lost window cost them the 2019 World Cup. You might remember reflexive changes to the All Blacks squad right before that 2019 World Cup — low-cap front rows and outside backs brought in from nowhere to replace veterans — but at that point, it was too late. These guys needed regular exposure four years earlier. By the time Hansen seemed to realise that the squad core had run their race, it was too late to upscale their replacements.

Maybe that friend of mine is wrong. Maybe it’s hubris. Maybe going finally 3-0 over Ireland, a team New Zealand looked at on the same level as Scotland in the 2000s, for the first time post-2016 went to his head.

On Monday morning, it feels like there could be something to it.

The secret to building a test side isn’t in moonshots out of nowhere because a retirement or a one-off injury forces your hand. It’s a gradual rolling boil. A perpetual stew. New players replace the old guard so gradually that they don’t even feel like “new” players until you really look at it.

It means cycling down your golden generation gradually, shocking them with selection for big games, and then slowly moving them out of the picture — even risking losing them from your system, as a result — with the idea that what comes after will be better. You prune, remove players right before they start to slip past their peak. If you’re doing it right, those guys get to go out on top and have people wondering if you moved too soon.

The alternative is your core being elite, world-class, hugely experienced players, the kind that win you test matches at the start of the year, and a faded photograph of that same player by the end of it.

You probably don’t even hear it when it happens, right?

***

I hate seeing Ireland lose to the All Blacks.

Forget about the squad make-up. I did just that on Saturday night when I arrived in after the Munster game with McDonald’s for myself, my fiance and our little girl (she was more interested in the deck of Uno cards that came with the Happy Meal, rather than the chicken nuggets, and we played cards until the game was finished).

I want Ireland to win. Always. I don’t care how many blue flags are next to the names on the teamsheet.

I’m long past the idea that Ireland losing will force “changes” because that never happens. Eddie O’Sullivan didn’t do it. In the end, Kidney couldn’t or wouldn’t do it. Joe Schmidt didn’t do it. Neither will Andy Farrell. Real change will come from whoever comes after him.

Irish head coaches become the team they constantly select because, by default, the players they don’t select are never theirs. And even then, who would you drop?

So in the absence of that, I went back to the Green Eye. What were the fundamentals discussed there? What worked? What didn’t? At a basic level, this.

The game followed the “NZ win script” I flagged: low-volume NZ entries, PPE ≥ 3.5, and Ireland losing the LBR differential. Territory split was pretty much even, as predicted, but Ireland never banked the entries cushion normally associated with wins in the last 18 months, and couldn’t keep NZ’s linebreak per ruck count down.

Checkpoints vs Reality

- Entries cushion (≥ +3 by 60′): Missed — Ireland 5 entries, NZ 7 (−2). This is almost a near-automatic win state when achieved, and we didn’t.

- LBR differential (≥ 0 by 50′, ideal ≥ +2): Missed — IRE 2/67 → 2.99 per-100, NZ 6/90 → 6.67 per-100 (Δ −3.68). Negative LBRΔ is Ireland’s 18-month red flag and showed up again here.

- Ireland PPE (target ≥ 2.5): Missed — 1.4 ppe.

- Keep NZ to ≤ 5 LBR/100: Missed — they hit 6.67/100.

- NZ win script (≥3.5 PPE on ≤8 entries): Hit — NZ 3.7 ppe on 7 entries (red alert stuff for NZ specifically, and for Ireland’s last 18 months).

- K:P guidance (~1:6–1:7, purposeful contestables): Ireland landed 1:3.9 — more kicking than I had in the target band, but without the entries pay-off (lineout 69%, restarts 67% undercut access).

TL;DR: Ireland’s Green-Light thresholds mostly went unmet, while two big red flags (negative LBRΔ and NZ ≥3.5 PPE on low entries) fired almost exactly as I hoped they wouldn’t.

So what do linebreaks mean? At a basic level, it means breaking the primary line of the defence with the ball in your hands. This is the ideal scenario to score a try, either directly from that linebreak, or on the next phase of play as the defence struggles to react. It’s not the only way to score a try — you can pick and drive from close range, or maul the ball over the line — but if you want to score a try in any other way, you need a linebreak from somewhere.

In Six Nations 2025, only 34.6% of Ireland’s linebreaks became tries (France 53.3, England 50.0, Italy 36.0, Scotland 29.4, Wales 19.0).

That’s lower than the average and well behind the two best finishers in the Six Nations. These metrics apply to almost every other game Ireland has played in the last 18 months, bar the win over Fiji.

What it means with LBR

- In the NZ test, Ireland’s LBR = 2/67 → 2.99 per-100 rucks. With a 34.6% conversion rate from the Six Nations, that yields roughly 1.0 tries per 100 rucks from break sequences.

- When our chance creation (LBR) is low and our finishing (LB→Try%) is middling, we need either a big entries cushion or set-piece/penalty scoring to keep pace. Ireland had neither vs NZ.

- The Six Nations offload profile backs it up: 70% offload success, but only 3.6% of successful offloads led to a break, and 0% to a try → this is confirmation of the eyetest; we offload to keep sequences going, but it’s low-leverage continuity, not kill shots.

- Carry detail: Ireland commits 2+ tacklers 55.1% (which is grand), but tackle-evasion is only 18.2%, so many “wins” still end in phase resets, not clean breaks — depressing both LBR and LB→Try%.

We don’t just need more linebreaks; we need better ones — supported and finished — so that each break is closer to France/England/New Zealand efficiency rather than what we have now.

So, against, how does this translate?

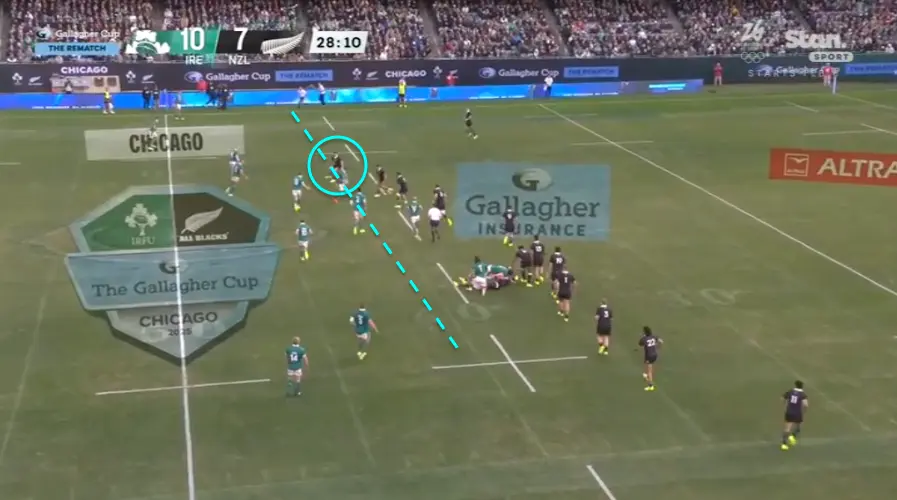

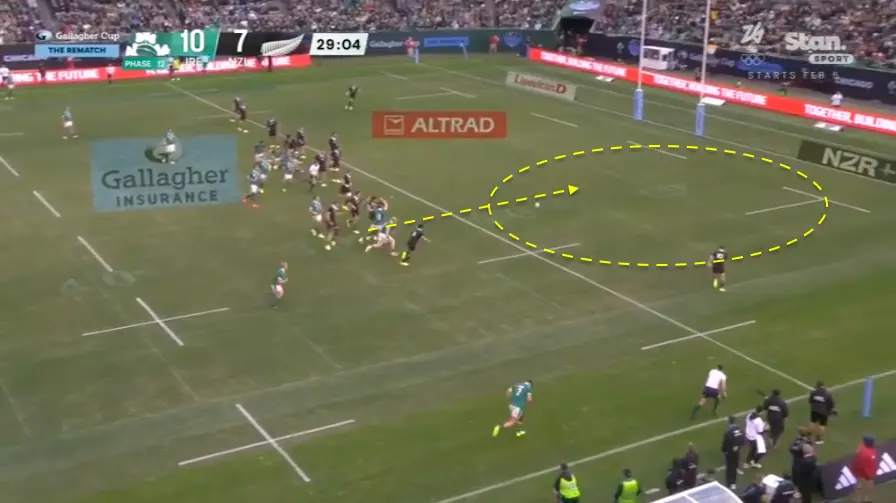

Here’s one of our two linebreaks;

Gibson Park finds Crowley on one of his trademark late-arriving blind-side snipes. Crowley commits a defender and offloads to Sheehan, with Conan on his inside.

The linebreak was snuffed out — and NZ infringed at the next ruck for a penalty — but that’s a good example of a linebreak we did create. It led to a penalty, and that’s a positive.

So what happened for the rest of the game?

I have a sequence of play that explains what I’m talking about.

Ultimately, we’re looking at the intersection of collision winning (and I have a different definition here than most), play from the resulting ruck with reference to the defensive picture, and then the play on the pass to the next collision.

Here’s the first clip, and to be clear, I waited until it was 15 vs 15.

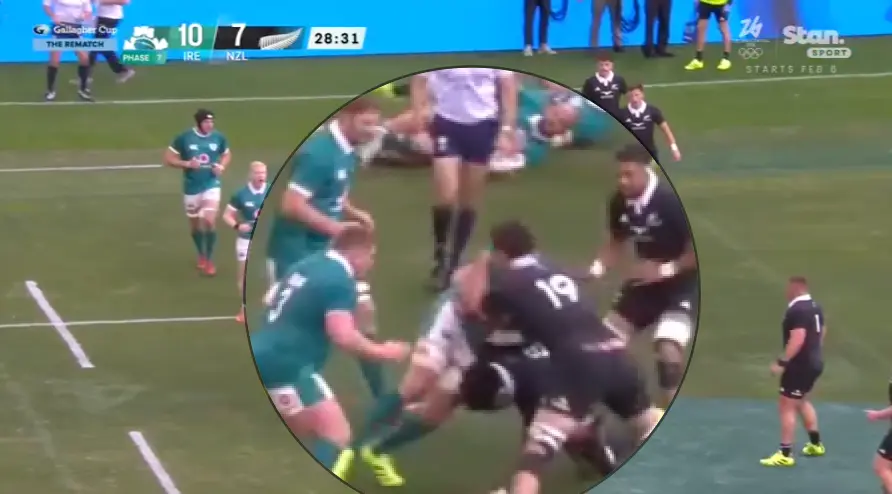

The only collision win here, as I would define it, was Josh Van Der Flier’s carry into Roigard, which compressed the same number of defenders to the collision point as attackers.

Every other primary line collision in that sequence failed in this regard.

New Zealand had a very specific defensive approach here, which many sides have used against this Leinster/Ireland carrying rotation with a lot of success. Essentially, make two-man stops, with the second man adding extras to a counter-ruck if possible, while the rest of the defence pack the pillars to stop Gibson Park — our primary linebreak generator between 2021-2023 — from sniping into the exposed fringes.

What teams have realised is that sending a third man over the top of the ruck to contest Ireland at the breakdown outside of the 22 is a fatal defensive mistake.

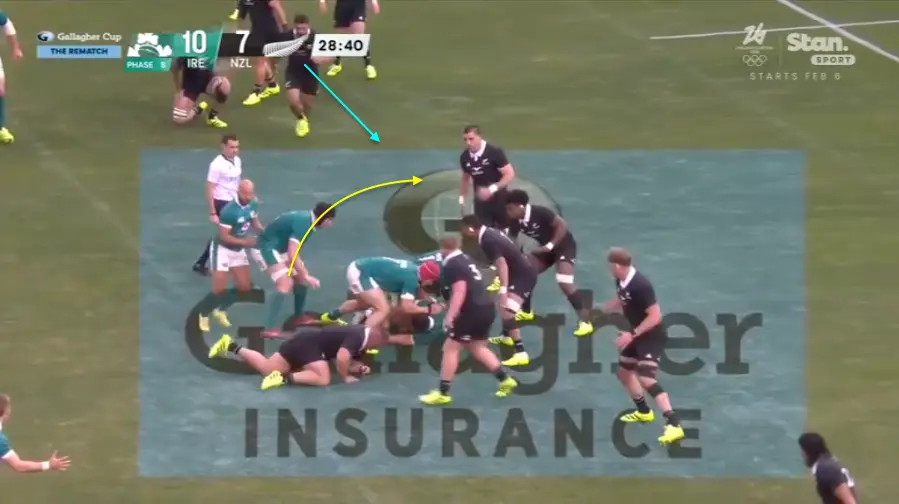

This is the picture you want in front of Gibson Park at any ruck.

No space to snipe. No folding defenders he can pick off, two defenders on the ground at most, and three Irish forwards on the ground.

When Gibson Park sees that picture, he tends to look for an edge-finder pass. The All Blacks edge has to step up onto the line of that pass — not blitz high into the second layer, but enough to make a screen or bridge pass a big risk — and force Ireland back inside.

Meet that with the same two-man/second man scraps defensive collision. Draw Irish forwards to the ruck. Don’t fold after the collision.

When we look to find the edge with Crowley on the loop, that edge defender has to shut the space before he can get his hands free.

When we reset, the same principle applies. Then it comes back to a fundamental point; can we put the same number of All Blacks on the floor than we take to win the next ruck?

The answer here is an emphatic “no”.

Lakai stops Ryan definitively, with our ruck support too far away to instantly win the collision point.

We lose three forwards to this ruck, and it’s slow anyway because Gibson Park is buried at the previous ruck. Ideally, Ryan would stay on his feet here to give Henderson and Furlong a chance to drive through on him and drag more All Blacks into the collision, but he’s stopped dead on contact.

Taylor actually makes an error at the ruck — goes off script — by trying to put off Osbourne, and Baird spots that on the next ruck.

But even then, we lost four forwards at the next collision point due to Lakai’s excellent poach that most other referees probably blow as a penalty to New Zealand.

But here’s proof of concept; Gibson Park thinks New Zealand have blown the fold, so he goes for the snipe when he sees daylight in the pillar, even though it wasn’t really there.

After this, Ryan got stopped one-on-one by De Groot again, so we looked to use a pre-designed kicking play to get around the defensive pressure.

Crowley tries a dab through for Ringrose and Osbourne to chase — we used this a few times — to try and use their defensive collision dominance against them, but Ringrose ran into Fainga’anuku and wasn’t able to follow up on the line.

It was a good option, tbh, and it was executed pretty well. That first bounce is exactly where you’d want it. I think Ringrose always knows he’s going to be blocked here, so it’s on Osbourne to chase.

I’d say that slightly exposes his lack of top-end acceleration — something I think limits him offensively at fullback, as we saw in Croke Park — but it mainly shows how difficult Ireland found it to generate positive collisions, especially when our primary engine for generating linebreaks (Gibson Park) is taken out of the game as a primary attacking threat.

So if you’re not creating compressions, and you’re not creating linebreaks, and your lineout doesn’t function, you try to play through that with a high-volume kicking game, but when you concede a few scrum penalties, that means it’s very hard to keep any territorial gains you make without clean offensive catches. We didn’t have enough of them.

It’s a recipe for losing any game, especially against the All Blacks.

| Players | Rating |

|---|---|

| 1. Andrew Porter | ★★ |

| 2. Dan Sheehan | ★★ |

| 3. Tadhg Furlong | ★★★ |

| 4. Tadhg Beirne | N/A |

| 5. James Ryan | ★★ |

| 6. Ryan Baird | ★★★ |

| 7. Josh Van Der Flier | ★★ |

| 8. Jack Conan | ★★ |

| 9. Jamison Gibson Park | ★★★ |

| 10. Jack Crowley | ★★★ |

| 11. James Lowe | ★★ |

| 12. Stuart McCloskey | ★★★★ |

| 13. Garry Ringrose | ★★ |

| 14. Tommy O'Brien | ★★ |

| 15. Jamie Osbourne | ★★★ |

| 16. Ronan Keller | ★★ |

| 17. Paddy McCarthy | ★★★ |

| 18. Finlay Bealham | ★★ |

| 19. Iain Henderson | ★★ |

| 20. Caelan Doris | ★★ |

| 21. Craig Casey | N/A |

| 22. Sam Prendergast | N/A |

| 23. Bundee Aki | ★★ |