Losing in Dublin in October – or what feels like October – should not shock Munster Rugby.

Not at this point. We last won this fixture in 2014, ten years ago.

Munster have had good seasons in that time, and bad seasons. Losing to Leinster in October hasn’t determined those one way or the other, besides stirring up a few hot takes the week after.

Ultimately, it defines nothing more than what we already know: a fully focused, mostly Category A selection Leinster team is better than a Munster team with a few critical injuries. But that shouldn’t be a catch-all handwave either. Go back to this fixture on the 6th of October 2018 – six years ago – and four of the starting front five are still the same. Beirne, Kleyn, Archer and Scannell. We’ve replaced James Cronin with Jeremy Loughman at loosehead. Beirne is still world-class. Kleyn can be at that level but isn’t currently as he works his way back to full clip after a year out. Scannell and Archer were good clubmen then and are now. But all of them are six years older, with six seasons worth of miles on the clock.

That reflects the bigger problem we’ve had in the interim; we’ve found it almost impossible to consistently refresh our tight five, and it’s our tight five that almost always loses this game.

That isn’t to say that Jeremy Loughman didn’t play well – he did, on top of being hardy as they come. Niall Scannell did well. So did Stephen Archer. John Ryan off the bench did well too. They were all part of the dominant scrum on the field. But my point is, even with them playing well it didn’t matter.

With that starting front five on the field, we had nobody who could power over the gainline like Furlong did here, and you have to ask if Andrew Porter would lose such a critical collision with Jack Crowley on the 5m line if the roles were reversed.

We know the answer to this. The answer is no. It’s not a black mark on any of those Munster players. Not everyone can be an elite front row with elite size and athleticism. I mean that in the kindest way possible because it sounds passive-aggressive but it’s a truism we have to acknowledge. Does Oli Jager win that collision with Frawley? Yeah. Does he win the one that Furlong does? Maybe. Does Salanoa on both counts? Yes.

But both men have been injured, one short-term, the other for the past 12 months.

At some point, we have to face reality; until we can upgrade the phase play power of our front row on both sides of the ball consistently, we will always look underpowered against any selection that Leinster have with Porter, Furlong, Ryan, McCarthy and/or, latterly, RG Snyman in it.

That’s just a fact.

All of that starting Munster front row are excellent scrummagers, for example, but I would posit that unless that scrummaging is also backed up with elite power in the middle of the field it’s no more than a cool gimmick.

Even then, what good is a scrum that wins penalties if you can’t secure the lineout that follows?

***

The adage of “No Scrum, No Win” is long dead.

You can update it with “No Lineout, No Win”.

I thought about this after the game on Saturday when I sat down to watch the same Blippi video with zoo animals in it that I had for the last few days with my little girl. She loves that screeching weirdo. I don’t get it. Anyway. This was my thought.

“A bad scrum can be negated by a good defensive lineout and a good scrum is completely negated by a bad attacking lineout”.

It’s like Live, Laugh, Love for people who allow their emotions to be dictated by a rugby team. When I’m doing these Wally Ratings, I want to be as fair as possible because I know players and coaches read them. I try to keep my criticism measured, essentially, so it’s with that in mind that I say this; Munster’s lineout is nowhere near the level it should be for a club with our expectations.

You can even see it in this nicely textured photo edited to give a 90s magazine vibe. Look at how weak Archer and O’Donoghue’s lifting positions are compared to Max Deegan. Want to know how a 6’9″ athletic jumper like Ahern didn’t look like either of those things in the lineout on Saturday? There you go. One of the reasons. Our lifting isn’t explosive.

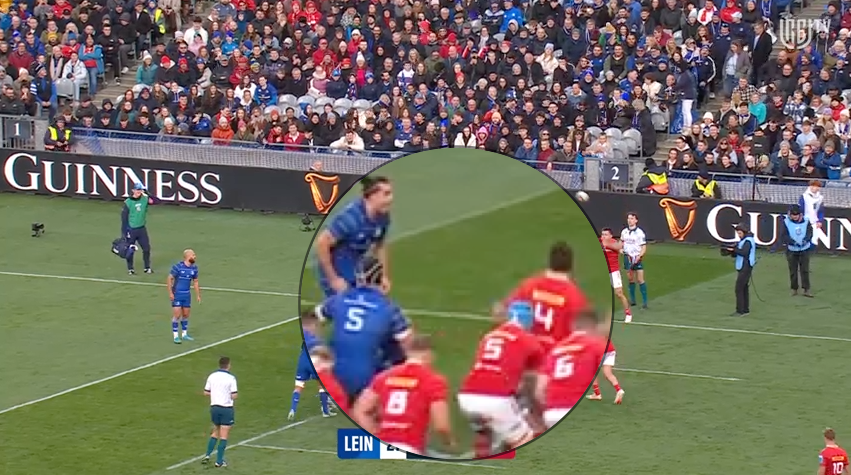

This was a great example of that. We’re down 21-0 – a point conceded per minute – with a 5m lineout opportunity to get back into the game. Look at Ryan labouring at the front to shoot Kleyn straight up.

Does Ryan jump across the lineout? Absolutely. But there’s no way we should be losing a front ball like this. Kleyn starts his jump before Ryan.

Yet the acceleration that Ryan gets from Furlong as the front lifter gives him more “pop” into the air. A frame or two later, you can see Kleyn is already starting to lose his shape in the air because he isn’t getting the same push into the air.

Kleyn is heavier than James Ryan, sure, but that means that the lift on him has to be stronger and more authoritative. When you see Kleyn starting to “salmon” in the air at this stage – having to adjust his body shape mid-jump – combined with reaching for the ball without Beirne or John Ryan being at full extension, you’re looking at a blown lift.

It happened throughout the game. Why is that happening in Croke Park against Leinster? That’s the crucial question. A few minutes later, you could see some of the same issues combined with timing problems. You can see it all here;

We went to a full lineout to throw off Leinster’s two-pod defensive system – Ryan at the front, Snyman at the middle and back – and had a walkup jump from O’Donoghue. This is usually a quick “flinch” move to get into the air and away before the opposition can get set for a jump with no maul build included in the set-up.

The idea is that Scannell is told by Ryan pre-throw to hit O’Donoghue when he hits the line in so many words. Scannell is queued up to release when he sees O’Donoghue line up with Coombes. Scannell releases a little early and O’Donoghue’s walk up and go seems to catch Coombes by surprise.

When you see the ball this far into the line with O’Donoghue a good few frames away from full extension… I’ll put it like this, he did very well to retain this.

This scrappy lineout counts as one of the 69% we retained in this game. Elite-level lineouts run at 90%, decent lineouts run at 85%+. Below 80% is bad. Below 70% is “what’s going on here”.

Last season, we had one of the best mauls in the league when it came to metres gained, which was all the more impressive because we had a below-average lineout behind it. You can see the base concept here against Leinster’s two pod defensive system.

Pay attention to that Loughman, Kleyn, Beirne pattern.

Loughman starts in a “race” position at the front of the lineout with his lead leg in. Kleyn leaves a lane for Loughman to potentially run through. In this instance, both Loughman and Kleyn run to build a 3-3 maul structure but it’s important because this is our base lineout structure.

Look at where Furlong is;

Leinster are not aligning with Loughman on the 5m line because they fundamentally don’t respect our ability to hurt them with a gimmick play at the front from this range. Munster, for example, couldn’t do this against Leinster with Dan Sheehan at hooker because of the risk of a 1-2 throw that would leave one of the most athletic hookers on the planet one on one with Craig Casey. Casey would make his tackle, but it’s the compression that’s the worry.

Leinster do not have to worry about the same thing with any of the current Munster hookers, let alone Niall Scannell who is many things; a good thrower, a good scrummager, a good and willing tackler, a good offensive breakdown player but does not have any kind of carrying or running threat from this range.

As a result, Leinster can focus on clustering their lifting and jumping resources into two tight pods that hurt where Munster want to build mauls – the middle.

On the next throw, you can see how Leinster’s defence worked.

First of all, look for Ryan shadowing Beirne – standing where he’s standing after the walk-up. Then look at Furlong standing tight, well inside Loughman’s line. Structurally, it looks the same as the previous lineout. Loughman is posed the same. Kleyn is leaving the same space with the same body shape. Beirne is walking up late. Leinster just missed the previous lineout, would we throw to the same conceptual space?

If so, they were ready.

Furlong is within a half-step of Ryan so he can sink into a lift easily. Conan is practically pre-bound to him as the back lifter. Porter already has hands on Snyman’s lifting pads. But it’s the design of this lift that’s the issue.

Count how many steps Kleyn has to make to get into a lifting position on this GIF. Compare that to how many steps Furlong has to make.

Two steps with a lateral swivel for Kleyn. Zero for Furlong. Barron’s throw will then have to be perfect to hit Beirne with this level of contest, but it’s a poor release with too much power-hand side lean. Essentially, the right hand that powers the throw was in contact with the ball a little too long at the release relative to the guide hand so the tail of the ball lost rotation before the nose of the ball did, leading to a wobbly throw.

A few minutes later, the lineout went from bad to worse with a completely unforced turnover that led directly to Leinster’s second try. From the start, it was clear that there was a bit of confusion on the call from Barron’s perspective or at least that’s my read on it. It doesn’t look like he has a tonne of clarity here.

When the throw comes in, it flies over the top of the lineout with no jump and the ball is turned over clean.

I think I know what happened here. I think Barron interpreted this movement from Beirne as an adjustment to the initial call; essentially a wipe of the previous instruction and an improvised call to throw it to him as he was open.

I think the actual call here was to hit O’Donoghue at the front and then maul break. That would explain the gap Hodnett has as the receiver. He can’t be too stuck to the drop or he’ll get tangled – he has to dart in and dart out. The reason I think this is because we used the exact same shape on the next lineout, something we often do after a mistake.

The same 5+1 shape, except Kleyn and O’Donoghue are in different starting positions. Throw to the front, maul feint and break.

When your lineout doesn’t function properly, it often leads to straight turnover tries like the above but at a base level it gives energy to the opposition and consistently relieves any territorial pressure you might have been building to that point. It also denies a platform from your creative players.

It’s the small details that are leaving us down and, for me, that points back to broad-brush coaching.

This is another great example from the first half. It’s a five-man lineout to cut out Leinster’s set two-pod defence. Essentially, they can’t have two pre-bound (or essentially pre-bound) counter-jumpers locked and loaded before the ball comes in. They have to leave a free lifter in the middle who, in theory, will have to move to assist the player in front of him as a backlifter and the player behind him as a front lifter.

That’s the entire concept of moving to a 5-man scheme with no receiver. You stress the free lifter in the middle of the lineout. So, for Munster on this play, that would be hitting the area where Snyman is patrolling because he’s the heavier jumper.

Here’s what happened.

We retain the ball – part of the 69% – but it was functionally useless to work with. Why was the ball so scrappy? Because the lineout scheme actually went against the logic of the structure. Snyman is the heaviest possible counter-jumper. Deegan starts the lineout facing Ryan, Leinster’s best counter-jumper, with a half-bind. Our movement runs Beirne into a race with Leinster’s only locked-in counter-jumper rather than forcing an isolation with their heaviest jumper.

When you see Leinster at full extension while Archer is slipping off his back lift, causing Beirne to sink from his apex – that’s small details costing us.

How is Ryan getting higher into the air on our throw? Sure, Leinster would have known a lot of our lineout philosophies coming in – they didn’t know the calls, as the lineout isn’t called in a place where they could hear it so the Snyman factor in that regard was a red herring – but we made this one easy for them.

The same was true on their throw for almost the entire game. Our defensive lineout is arguably worse than our attacking one given the personnel we have. Jack O’Donoghue, for example, is a great counter-jumper. He’s tall, he’s got a big wingspan and he’s light enough to be lifted well by pretty much anyone that’s set up to lift well.

What do you notice about this counter-lift?

If you said “Stephen Archer is in a fundamentally weak, off-centre lifting position so he can’t possibly lift O’Donoghue up. He can only lift him across, and slowly at that.

O’Donoghue gets nowhere near Deegan’s jump and, if anything, risks giving away that daft jumping across/playing the man in the air penalty we seem to concede every game.

Now, I will balance this by pointing out that our first try was scored with a nicely designed lineout scheme that saw O’Brien loop from the front of the lineout to a perfectly engineered gap at the tail of the lineout without a maul feint, which is nice going, but the numbers speak for themselves; 69% lineout completion against Leinster have you beaten before you do anything else.

The lineout problems persisted well into the second half and cut any attempts at engineering a comeback against a stuttering Leinster side off at the knees. It’s the same thing. Poor lifts that turn our ball into turnover Leinster ball.

In this instance, Deegan jumps across into Ahern – it should be a Munster penalty – but look at how poor our lift is.

The front lift by Ryan doesn’t have the proper extension. The back lift by O’Donoghue is late and has no power.

Scannell’s throw is too low so we don’t even get the use out of an athletic 6’9″ jumper with a massive wingspan. It’s thrown to an area where Deegan can get it and where we can only miss it if we have a bad lift and a bad throw.

Until the lineout is fixed, nothing else will matter against elite opposition.

Our bad start is directly tied to this because you can absolutely lose an early score to Leinster and still beat them; better sides than us have done the same and stemmed the bleeding immediately.

We can’t stem the bleeding because whenever we get an opportunity to build phases and pressure – literally keep Leinster from playing on their terms – we lose lineout after lineout.

That has to change before anything else is able to.

| Players | Rating |

|---|---|

| 1. Jeremy Loughman | ★★★ |

| 2. Niall Scannell | ★★★ |

| 3. Stephen Archer | ★★ |

| 4. Jean Kleyn | ★★ |

| 5. Tadhg Beirne | ★★★ |

| 6. Jack O'Donoghue | ★★★ |

| 7. John Hodnett | ★★★ |

| 8. Gavin Coombes | ★★★ |

| 9. Craig Casey | ★★★ |

| 10. Jack Crowley | ★★★ |

| 11. Sean O'Brien | ★★★ |

| 12. Alex Nankivell | ★★ |

| 13. Tom Farrell | ★★★ |

| 14. Calvin Nash | ★★ |

| 15. Mike Haley | ★★★ |

| 16. Diarmuid Barron | N/A |

| 17. Keiran Ryan | N/A |

| 18. John Ryan | ★★ |

| 19. Tom Ahern | ★★★ |

| 20. Ruadhan Quinn | ★★★ |

| 21. Conor Murray | ★★★ |

| 22. Tony Butler | N/A |

| 23. Shay McCarthy | ★★★ |