Have you ever heard of the Coastline Paradox?

Well, you have now. I was sitting in bed a few weeks ago, back when my little girl had a cough that spluttered up every few minutes, so sleep was impossible. As you do, I was endlessly scrolling until I came across this paradox. We don’t know the exact length of Ireland’s coastline, or any coastline for that matter. It’s all our best estimate based on our ability to measure it and the degree of cartographic generalisation used.

If you want to measure the circumference of [looks around the room] a picture frame, you can get a ruler and measure up the sides and the top and get pretty much an exact number. Doing that with a coastline really does depend on the size of the ruler you’re using.

What is Ireland’s circumference? Well, that depends.

Reports of the length of Ireland’s coastline vary widely. The World Factbook of the Central Intelligence Agency gives a length of 1448km. The Ordnance Survey of Ireland has a value of 3,171km. The World Resources Institute, using data from the United States Defence Mapping Agency, gives 6,347km.

Why is the Ordnance Survey of Ireland measuring 3,171km? Because their step size measurement is 1km. If you reduced the measurement to 1 meter, the coastline would measure 15,550 kilometres. Down at 10cm, it’s longer again. That’s the power of fractals. You can always go deeper, and nobody can tell you the exact measurement of any coastline.

Fixing a lineout is broadly the same. There’s always a smaller measuring stick to go to when it comes to getting to the elite level. At a grand scale, you talk about throwing the ball and jumping, drill down, and you get into grips, ankle extension, and how high you’re mauling at, but you can go deeper than that again if you want.

When it comes to the lineout, small things become big things pretty quickly.

Alex Codling loves the small things when it comes to the lineout. If you get your small details right, they scale up to look after the big details. As an example, when you see a dud lineout throw, it’s easy to blame the hooker (and fun, too), but more often than not, the problems are deeper than that; a bad lift coming from a bad grip, the bad grip coming from a bad foot position, and all coming from back to back (to back) bad week’s in training where small details got passed by to move to the next session.

Small things become big things.

And fixing the small things needs focus.

***

It’s not news to you that Munster’s lineout was pretty bad last season on the whole, albeit with some real improvement immediately after Alex Codling entered the building before degrading again right after he left for the Women’s Six Nations.

What does a good lineout/forward coach do? They sweat the small things.

Alex Codling might not have been in the building all summer — he didn’t officially start with Munster until last week, after his work with the Irish Women was completed at the World Cup — but his blueprint for the rebuild of Munster’s lineout was in place, along with a few check-ins over the summer before the World Cup really kicked into gear.

At a base level, Munster didn’t have a very athletic lineout last season, for most of the season anyway. In practice, this meant that we weren’t explosive going into the air, and that was either due to the jumpers we had, our lifters, or both.

This was really noticeable at the start of the season. This article is harrowing to look back on, with the game against Stormers a week later even worse. It’s not just that we’re losing lineouts in two games — every team, even ones with elite lineouts, has bad days or gets targeted successfully by a team having a good day — it’s about the underlying concepts that your lineout is based on.

Last season, and the previous two, the main focus of our training sessions was about speed and intensity, first and foremost. We wanted to train under the conditions that were closest to a game, where there were no real do-overs, and everything was quickly moved “onto the next”. This was noted directly by Billy Holland here. It was about playing quicker, and making sure we were up to speed, quite literally, with the quicker game World Rugby said they wanted at the time, as well as being more battle-hardened in particular. Rowntree intended to get around Munster’s relative lack of top-end size and power in the front five with the pace of the game we played at.

And it was successful.

After a while, though, the cracks began to show. We were training at pace, and, from the outside looking in, it seemed like detail was being lost. Far from taking that pace into games, it seemed like we were hurried and prone to fluster. Year Two was a bad year for Munster’s lineout – fourth bottom of the URC for completion — and the start of Year Three was, well, catastrophic.

So what is Alex Codling bringing? Well, in concert with the new head coach, he’s bringing that focus and, in short, that means more focus on the small details in the lineout. Watching Munster train in Castleisland this summer, and in the HPC, there’s real time being spent on making sure the lineout structure is correct and that basics are being executed.

We saw a bit of that against Scarlets and, while that is encouraging, there will be bigger tests to follow.

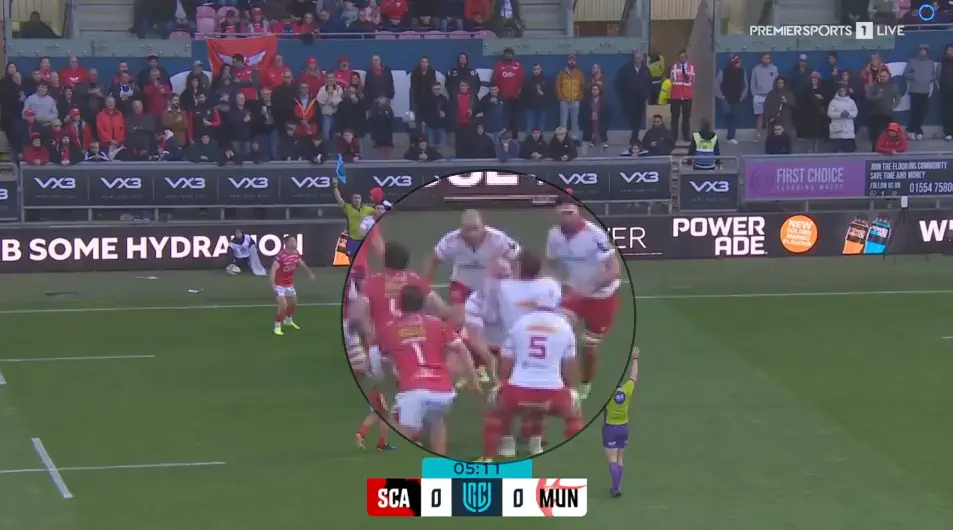

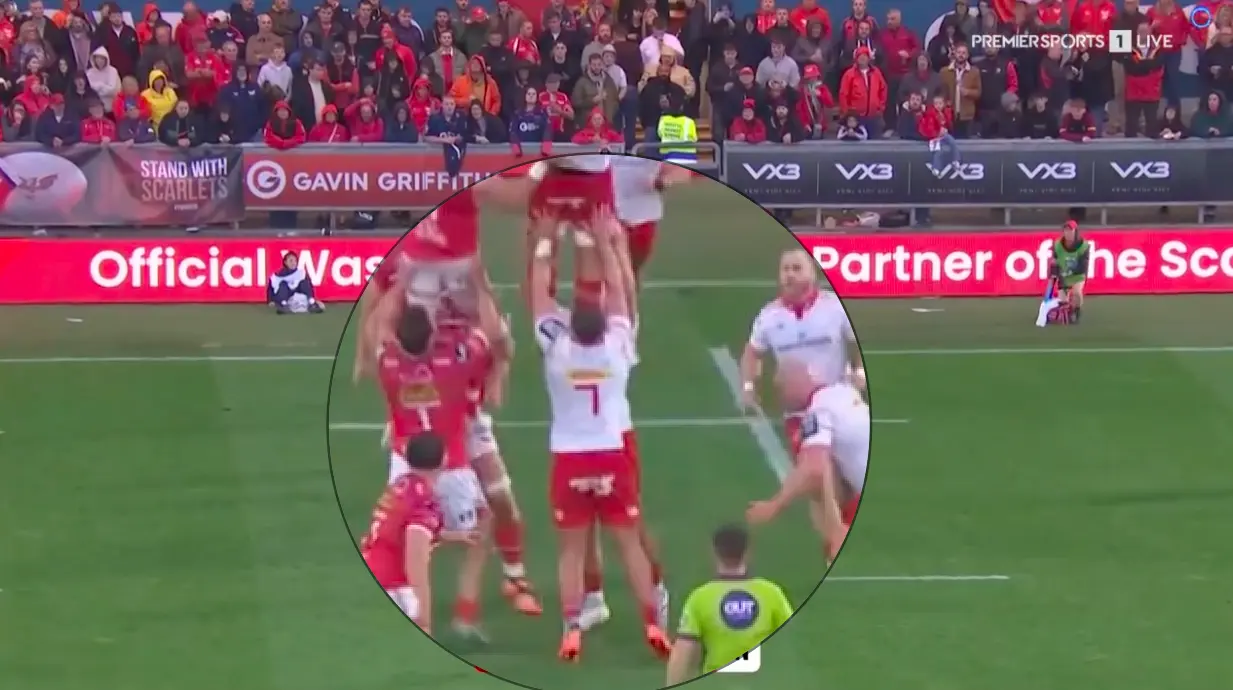

Here’s a good lineout to start — it’s a 5+1 with the Scarlets using Taine Plumtree, their best counter-jumper, at the front.

What do we see here? First, Kleyn and Jager — who is playing as the hinge here — do a great job of selling the counter-pod at the front that we’re jumping at the front. The first movement looks like a lift.

That holds Ball as the back lifter long enough for Jager to spring back and get a good uncontested lift on Jack O’Donoghue for a clean take. Look at Wycherley’s strong lift position here, with Jager arriving right on time to assist.

That’s a clean take in a nice, uncluttered window, and, for me, it probably should have been a Munster penalty for the player jumping across into our maul build, but we play out from it.

Kendellen is the rip in this position as our +1, but look at how quickly Kleyn and Loughman have gone from that front pod into strong drive positions at the back of the maul. This is also a consequence of jumping at the edge of the front — our heavier runners don’t have to cover extra ground to get into position.

Last season, a real bugbear of mine was how spaced out our lineout was, and how much pressure that put on our heavier players to move 6/7m before the drop. When that space is 5m or below, they get into position quicker.

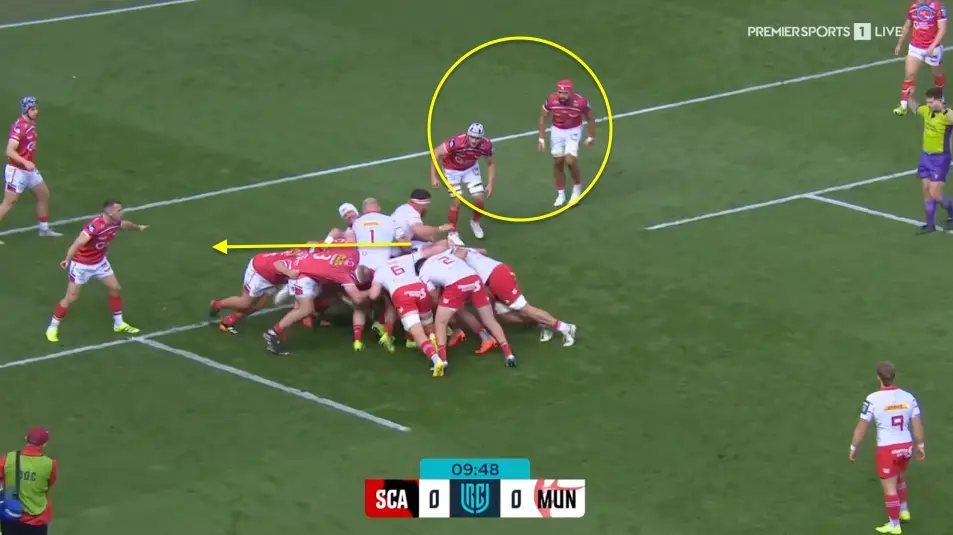

Let’s have a look at our first try.

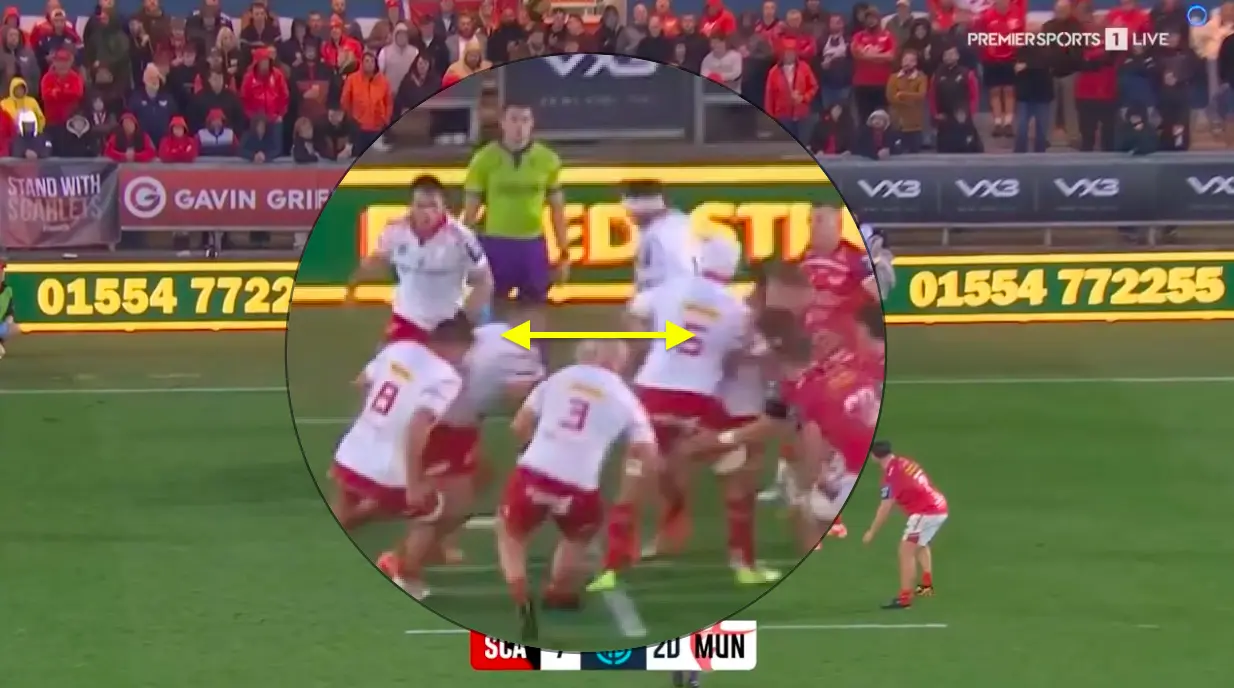

There’s nothing too outrageous here; just good basics. Our starting spread is quite wide because, as with most teams, we want to make sure that the defensive counter-shove has as few initial defenders as possible. The tail of our lineout then has to win the race to the shove; get in nice and heavy before the players marking them can sink into the shove.

We do this quite well, but our concept for the maul helps this.

Our intent is to always drive this towards the touchline, so that the flank defenders are compelled to commit to the shove early. We’re going into that initial defensive wall, and that will give initial momentum that will always interest flank defenders.

Wycherley is really driving into this opposite man here and he was so successful in that angle that the TMO went looking for “double banking” but I think that was a bit of a reach. Our drive angle was always diagonal towards the corner flag, almost, so the natural direction for Wycherley was going to be across — that said, another referee might well have gone along with the double-banking concept.

Regardless, it did the job. Four Scarlets forwards are caught on the touchline side, which leaves a massive space to break into on the posts side.

You can see the angular pressure from Kleyn, in particular, really come to the point here and open up that space for Casey to break, but it could have been Scannell, too. In an ideal world, it’d be Lee or Diarmuid Barron making that break in a similar circumstance, but Casey does really well.

There’s nothing remarkable about this; it’s just a good, simple concept executed really well, and most of the time, that’s all it takes.

All through the game, you could see our lifting positions benefit from that simple execution. Look at Kendellen here; straight arm lift, great pop and full extension through the boots to get as much height into the lift as possible.

That buys you time, it gives you clean windows to catch at the top of the jump, and it sets a great mauling platform.

Making Munster’s maul something that we can build attacks off has been a concerted focus of the squad all summer. You won’t necessarily do that with complex maul builds. Most of the best mauling sides don’t really do that, anyway.

Munster consistently used a 3-3-1/2 maul build here; three players as part of the lift unit, three powering in behind with the ripper in the middle and the hooker and/or another backrow stepping in at the tail to finish the build.

Here’s a really good example of that build, and how it can turn a banker throw at the front of the lineout into something destructive.

Pay close attention to Oli Jager here.

His leg drive on Fineen Wycherley here is really impressive and it chews away at the Scarlets infield defence. Lee Barron breaks a little early for me here — there was a penalty to be soaked out of the Scarlets — but simplicity did the job here. A good lift, a good “sink” where the Wycherley brothers have full control of Ahern in the air, so can time a solid sink into the Scarlets counter-shove on the drop, with a punchy three-man drive unit driving into that space.

That space gives you a metre or two of forward movement by default, but you only get them when you’re in full control of your lift and drop, when the opposition can’t shove until the very end and, if you’ve established your maul as one that goes forward, referees are automatially hot on early counter-shoves, which allow you to walk into the opposition’s 22 on back-to-back penalties.

When you have that control, you own the space, and the drive can push into it.

A strong maul cleans up the airspace around your lineout, as teams know that if they overcommit in the air, that you will drive through as a unit in a way that lead to killer penalties.

When your maul is there simply to compress defenders, you invite more aerial pressure. Keep an eye out for Munster continuing to use the maul against Cardiff to send a message, if nothing else; the Munster Maul is back.