In a broad sense, every club is in something of a quandary at the current state of the game, whether they are currently doing well or not.

A really good example to look at is the Stormers.

Last season, they were arguably as poor as they have been in the URC era. They were the inaugural winners, beaten finalists the season after, beaten quarter-finalists to the eventual winners Glasgow the year after that, before losing to Glasgow again last season, who exited at the semi-final stage.

In the offseason, they reassessed their style. They kicked the ball 430 times in 19 games last season and, so far this season, they’ve kicked 211 times in just eight — that’s about a +16.5% higher kicking rate than last season. But they’ve supercharged that with a much improved lineout and a scrum that has improved in leaps and bounds.

For example, in last year’s URC — again, 19 games for the Stormers — they won 42 scrum penalties. This season so far, they’ve won 35.

If they held this season’s rate across the same 19 games, they’d project to:

4.38 × 19 = ~83 scrum penalties won (vs 42 last season), i.e. ~+41 and almost double.

For context, at last season’s rate you’d expect ~17.7 scrum pens after 8 games; they’re on 35 (about +17 ahead of that pace).

They’ve made some key signings that have helped that — Mchunu, Van Wyk and Oli Kebble, in particular — but you could also look at the development of guys like Sazi Sandi, Zachary Porten and Vernan Matongo, and the fact they’ve made these strides without Frans Malherbe, who’s been unavailable through injury.

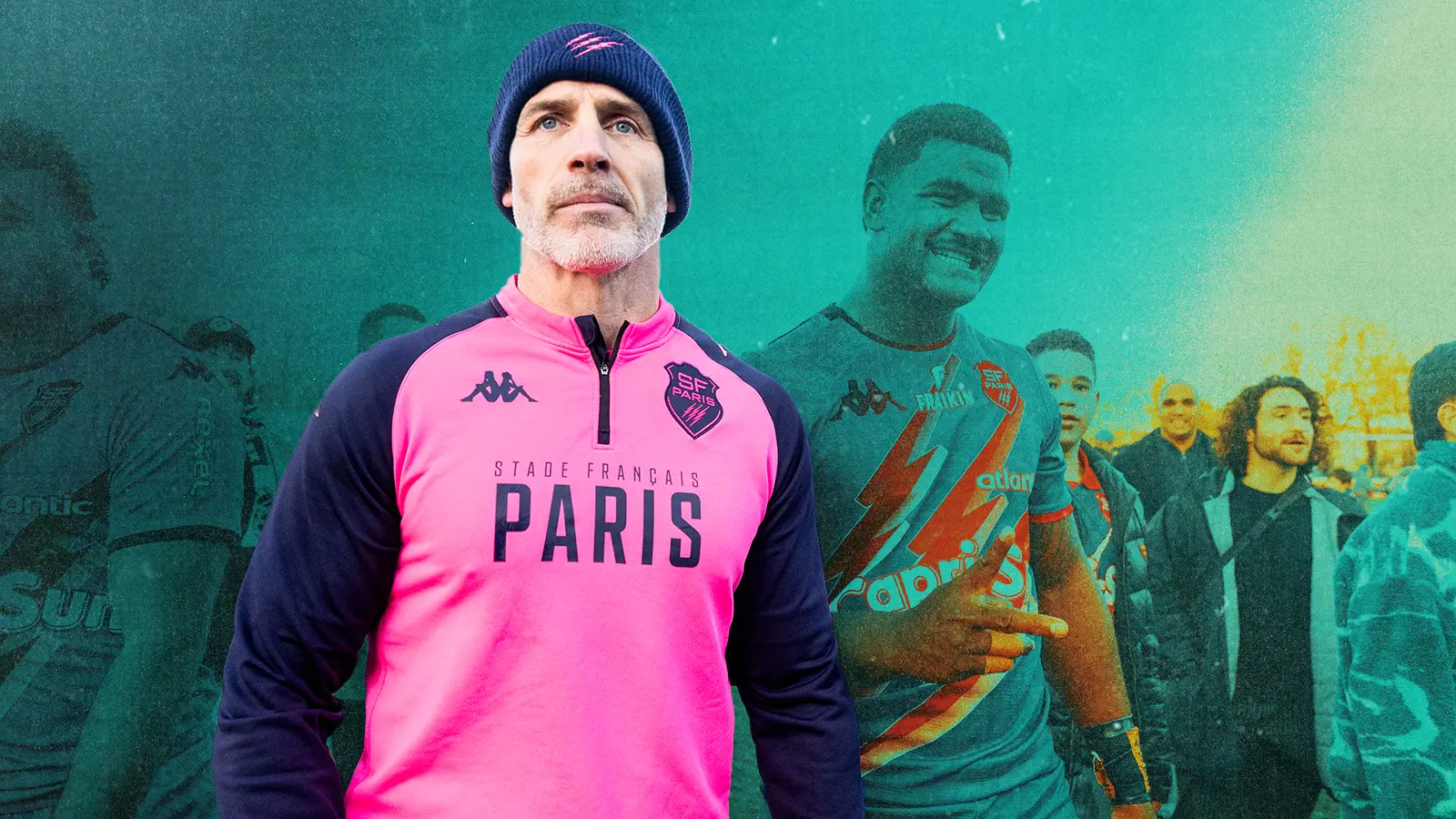

Of all the teams in the URC, just 8.3% of their possessions have gone longer than five phases. Only Stade Francais are lower, and Toulon are just one percentage point higher. The Stormers top the URC at the moment, and will likely finish 1st as it currently stands. Toulon are second in the TOP14 and Stade Francais have gone from flirting with relegation in the TOP14 last season to being comfortably in fifth place — as much as anyone can be in the TOP14 — this season. With Paul Gustard — yes, him of the offering fellas out for a scrap in Thomond Park last year before ducking out — in charge, that shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone. A defence coach by nature, a game that prioritizes high level kicking should be no surprise.

When we compare the data on all three teams, we find a few overlapping edges.

All three profiles are different flavours of the same modern, pressure-led template: short possessions, a high “kick reset” rate, and tries that skew toward platform and the chaos immediately after it, rather than long phase-build.

They all end a very similar share of possessions with a kick (Stade 41.5%, Toulon 39.8%, Stormers 38.7%) and rarely go beyond 5+ phases (Stade 7.6%, Stormers 8.3%, Toulon 9.7%).

In contact they’re likewise clustered: gainline success sits in the same band (Stade 61.4%, Toulon 59.3%, Stormers 58.0%) with comparable “two-tackler” gravity (Stade 45.7%, Toulon 45.5%, Stormers 50.1%), which supports that meta choice to play for territory/pressure rather than endless retention.

And they all get a majority of their tries from set piece (Stormers 72.4%, Stade 59.6%, Toulon 55.6%) with Stade acting as the stylistic bridge — more contestable-kick intent than Toulon (11.5% vs 9.8%) and more transition/offload punch than Stormers (offloads leading to try/break: Stade 11.4% vs Stormers 3.9%), while Stormers remain the purest “platform + pressure loop” version of the model.

Shared Connections

- % possessions ended by kick: Stade 41.5 | Toulon 39.8 | Stormers 38.7

- % 5+ phases: Stade 7.6 | Stormers 8.3 | Toulon 9.7

- Gainline %: Stade 61.4 | Toulon 59.3 | Stormers 58.0

- % set-piece tries: Stormers 72.4 | Stade 59.6 | Toulon 55.6

- Contested-kick %: Stormers 15.3 | Stade 11.5 | Toulon 9.8

Defensively, all three sit in the same modern baseline bucket: mid-to-high 80s tackle efficiency, a meaningful chop-tackle component, and an emphasis on winning the next moment (exit/pressure) rather than living off pure turnover volume. The connective line holding them together is that none of them are “miss-tackle chaos” sides; they’re broadly stable, and they all defend in a way that supports a kick/territory game.

Where they separate is how they create damage: Stormers are the most disruptive (line speed/denial + dominant contact), Stade are a balanced “pressure” defence, and Toulon are the least turnover-oriented and the leakiest in terms of misses that become breaks/tries.

Data bullets (defensive profile):

- Tackle success % (all clustered): Stormers 86.0 | Toulon 86.0 | Stade 87.2

- Chop-tackle tendency (hips or below %): Stormers 32.9 | Stade 30.3 | Toulon 28.3

- Gainline denial % (line-speed/stop power): Stormers 35.7 | Stade 25.5 | Toulon 24.2

- Dominant tackles % (collision authority): Stormers 8.1 | Stade 6.4 | Toulon 5.4

- % missed leading to try/break (damage control): Stormers 19.4 | Stade 25.3 | Toulon 28.9

- Rucks per jackal (lower = more jackal frequency): Stormers 25.9 | Stade 26.0 | Toulon 43.9

- 22 exit success % (supports defensive game model): Stormers 96.2 | Toulon 89.1 | Stade 86.2

All three can keep tackle completion high and use chop/low tackling as part of their system; none are built on frantic turnover gambling. Stormers and Stade both pair that stability with real pressure creation (higher denial/dominant contact and/or more frequent jackal shots), while Toulon’s defence is closer to “hold and fold” — reliable enough to function, but less likely to directly win the ball and more prone to misses that turn into immediate scoreboard events.

If this style is producing successful outcomes — two wildly improved outcomes from last season, and a further development in Toulon’s game — what does that say about what other teams should be recruiting?

It’s a key worry for a lot of teams, especially those who’ve found themselves pushing water uphill in recent games against teams who’ve specifically tailored their game to the new meta in preseason and who are recruiting for it as we speak.

Quite simply, if you decide to go all in on the new meta, that means a specific decision; game plan, training but most importantly, who you retain, who release and who you sign.

If you are recruiting specifically for the “pressure meta” (contestable kicking, higher scrum event-rate and penalties, exits as a weapon, and strike rugby off regathers/poor receptions), you are effectively buying two things:

- Pressure creation (territory, aerial contests, scrum penalties, dominant collisions, line-speed)

- Pressure conversion (turning those moments into entries/points without bleeding errors)

Below is how that translates into position-by-position targets, and why it can become expensive (and risky) if the meta swings back toward longer possessions, fewer scrum penalties, and cleaner kick receipts.

The core recruitment lens for the New Meta

A. “Repeatable advantage” traits

- Low-variance execution under fatigue (late-game scrums, late exits, late high-ball receipts)

- Discipline (pressure meta produces lots of whistle moments; you cannot leak cheap penalties/cards)

- Collision resilience (you’ll live in aerial and set-piece collision zones)

B. “Moments” metrics

- Scrum: penalties for/against per 80, stability late in games, penalty type (hinge/angle/bind), referee sensitivity

- Kicking: exit success, kick-to-contest accuracy (landing zone + hang time proxies), kick regains forced, kick errors conceded

- Aerial: contest volume, win/neutral rate, error rate under contest, chase penalties conceded

- Contact: dominant % (attack and defence), 2+ tackler gravity, gainline denial %

- Transition defence: tries/breaks conceded within 1–3 phases after kicks/turnovers (the “tax” of playing this way)

Position-by-position: who to recruit

Props: “penalty certainty” beats “survival”

Tighthead: the meta’s keystone

Role: generate or at least control scrum outcomes; turn scrums into territory/3s/cards.

What you prioritise:

- Low-variance stability (square set, stable long bind, no late hinge)

- Penalty delta (won vs conceded) and type (not “coin-flip” collapses)

- Q4 repeatability (scrum outcome doesn’t degrade when tired)

- Close Range Size (player has to be big enough to add tight collision value on both sides of the ball)

Loosehead: stability + engine, without penalty risk

Role: keep the platform intact and feed the pressure game (defence/ruck/chase work).

What you prioritise:

- Penalty discipline under stricter scrum/maul interpretations

- Work-rate that supports kick-chase and first-two-rucks

- Enough carry dominance to keep defenders honest when you do play

Why this is meta-linked: if scrums/penalties rise, every “free” platform win becomes an entry, and every conceded scrum penalty becomes an exit failure or a defensive 22 entry you have to expend energy to repel.

If the meta flips away: you risk overpaying for props who are dominant only in set piece but constrain ball-in-play pace (transition defence, repeated accelerations, handling in wider channels).

Back row: why the classic small forward gets squeezed

In this meta, the breakdown is still important, but the way you win games is often:

- exit cleanly,

- contest in the air,

- win the next collision,

- force the error/scrum/penalty,

- cash it out.

That favours bigger, faster “pressure back rows” over small forwards who might specialise in defensive volume, edge running and breakdown pressure. At a base level, if everyone starts playing less multi-phase sequences, there is literally less phases for a breakdown dominant player to impact the game; we’re already seeing this at Munster with Tadhg Beirne, who plays like a 6’6″ small forward in some ways.

And even their usual ability in the wider spaces becomes somewhat obsolete too, unless they happen to be a freakishly powerful runner or equally as freakish pace-wise.

Essentially, if they aren’t adding size in the middle spaces on both sides of the ball, or capable of contesting in the air themselves, then their primary role will get eaten up by midfielders (the new small forwards) or wingers.

The “pressure 6/7” replaces the classic openside

Role: line-speed, dominant contact, chase integrity, and selective jackal shots (not constant gambling).

What you prioritise:

- Gainline denial / dominant tackle output

- Chase speed + discipline (no cheap penalties when contesting kicks)

- Ruck arrival speed to secure messy regather ball

All of these are typical small forward traits, but teams are increasingly looking for players north of 6’3″ and 110kg to play these roles as pack alignments get narrower and fewer possessions put a premium on raw power and size in these spots.

Why the small forward suffers: if referees reward dominant collisions, set-piece penalties, and contestable outcomes, the marginal value of “I can win 1–2 extra jackals” drops versus “I can stop your first carry and keep your exit under siege.” That doesn’t mean small forwards will disappear from the game, it just means you can really only afford one senior option, with an academy option to add some role depth. That player will be purely horses for courses or used as a bench change-up in certain game plans if they are a high volume defender; Sam Underhill is a good example of this, as is someone like John Hodnett.

That’s before you get to the value of having a bigger body as the +1 in a lineout, or ideally as a jumping option themselves. In a broad sense, in the game as it stands right now, you can’t afford someone in your back five who isn’t a lineout option, and that’s really difficult for anyone 6’1″ and under.

If the meta flips away: you can get caught with a back row that wins collisions but lacks:

- repeated width coverage,

- linking/passing,

- multi-phase attacking decision-making, which becomes decisive in a possession-heavy game.

- ruck coverage dips in wider phase sequences.

Halfbacks: exit control + contestable execution become non-negotiable

9: “exit launcher” more than pure tempo

Role: produce a consistent box-kick platform and connect defence to the chase.

What you prioritise:

- Box-kick accuracy (hang + landing zone) under pressure

- Exit success rate (especially after slow ball)

- Speed of reorganisation after regathers (attack-to-defence-to-attack)

10: territory manager + “play off the compete”

Role: decide when to compete vs find grass, and then punish the disorganisation created.

What you prioritise:

- Touch-finder consistency and exit reliability

- Contestable variety (cross-field/spiral bomb/long range wiper) to target specific backfield shapes

- Error control (pressure meta amplifies single mistakes)

If the meta flips away: kick-first 9/10s can become a drag if the winning formula becomes:

- sustained multi-phase possession,

- edge-to-edge shape,

- high pass volume and repeat width creation.

Back three: aerial outcomes + backfield management are the “meta tax”

Wingers: one chaser, one aerial finisher (at minimum)

Role: win/neutralise the air and enforce the contest without conceding penalties.

What you prioritise:

- Aerial win/neutral rate

- Error rate under contest (this is the real killer KPI)

- Chase discipline (penalties conceded per contest)

Offensive kicking teams have a 60% chance of retaining possession on a contestable kick against the defensive side, with the margins going higher still if you can force a scrum which, ideally, your pack can convert into a penalty regardless of the put-in.

All of a sudden, a smaller, more agile winger is somewhat obselete, unless they are the elite of the elite who also happen to have an outsized impact in the air on both sides of the ball. Look for Ethan Hooker (6’4″) and Canan Moodie (6’3″) to become the defacto Springbok wingers in the next 12 months, with Van Der Merwe, Arendse and Kolbe competing for transition killer roles as the rest of the test sides begin to adapt as South Africa (and England) already have for this very reason.

15: the backfield controller

Role: solve exits, defuse defensive contestables, and convert clean catches into return pressure (carry or counter-kick).

What you prioritise:

- High-ball security + collision tolerance

- Decision speed on first touch (kick/carry/pass)

- Counter-kick accuracy to turn pressure into territory

As it stands, your fullback probably needs to be 6’2″ or taller, play close to 95kg+ and be an excellent long range kicker, as opposed to being a second creative presence or counter-attacking slashing playmaker.

If the meta flips away: pure aerial specialists can lose disproportionate value if contestables reduce (interpretations change, teams kick less to compete). Their wage remains “meta premium” while their influence drops. Think of England’s Freddie Steward’s last 12 months post law change and his value relative to someone like Marcus Smith at fullback for a good example of this.

Why this gets costly if the meta shifts away

You overpay for specialists whose value is meta-dependent

- Aerial specialists, box-kick 9s, maul/set piece forwards can lose marginal value quickly.

- Their contracts do not adjust downward when interpretations change.

Squad composition becomes mismatched

A pressure squad tends to be:

- heavier in the tight five,

- more kick-oriented in the spine,

- more collision-centric in the back row.

If the meta swings to:

- longer possessions,

- higher ball-in-play,

- fewer scrum penalties,

- less aerial contest emphasis,

you can be left with a squad that is too slow, too narrow, or too kick-first.

Injury and availability risk inflates

Pressure rugby concentrates collisions in:

- aerial contests,

- scrums/mauls,

- tight collisions

- kick-chase contacts.

Those roles can carry higher durability costs. If the game shifts to pace/space, you might still be paying for bodies built for collisions while needing lighter athletes built for repeat speed.

Opportunity cost: you lose “multi-meta” versatility

The safest long-term signings are players who still deliver if the meta changes:

- props who can scrum and play (work-rate, handling). These are incredibly rare.

- back rows who can both chase and pass, while also large enough to be force multipliers.

- 10/15s who can manage territory, kick accurately and run a multi-phase attack to a very high level — again, incredibly rare.

- back threes who are aerially sound and genuine linebreak threats while also being capable of looping inside as alternate playmakers. Again, incredibly rare.

If you ignore that and recruit narrowly, a law emphasis change can force you into another expensive recruitment cycle.

The best hedge: recruit “meta-proof” versions of these roles

Instead of buying the pure specialist, buy the player who:

- meets the pressure-meta minimum bar (scrum, air, exits),

- but also has the athleticism/skill for a possession/width swing.

In practical terms: when two candidates look similar for the current meta, pay extra for the one with additional passing, repeat speed, and decision-making, because those traits travel across interpretations.

In reality, those dual-meta players are incredibly rare to develop or sign and, as has often happened when the law has tweaked, some players will fall outside the elite bracket until they either retire or the law swings back to something that favours them.

I keep thinking of the ELVs back in 2009; far more wide ranging than the knock-on effects of the escorting law tweak, but they essentially changed the requirements for what was needed from your halfbacks in a season or so.

How much longer could Ronan O’Gara have stayed at the top of the game if he could continue to drop back into the 22, far away from any pressure, and kick to touch? That law change along heralded in the box kick and, essentially, ended the elite career of Peter Stringer in favour of guys like Tomas O’Leary and Conor Murray, who could box kick at a high level. You could even argue that the emergence of Johnny Sexton from 2009 on was a direct result of needing a #10 who could, essentially, play with the physicality of a midfielder.

The question is; what roles will the new meta make obsolete? It’s important to know that, because if you get it wrong you’re making expensive mistakes that can’t be easily corrected.