Here’s one for you; is Jack Crowley having a good season?

Thankfully, I think we can look at this question in the big 2026 without the toxic spectre of The Discourse rearing its head again, and I think you know what I mean by that. It seems that particular debate will soon be swinging around to Byrne vs Prendergast in Leinster, leaving the rest of us to step back and look at things a little clearer.

I was sitting in the wave pool in Centre Parcs the other day — in the periods where my lovely fiancé was running around after our domestic terrorist two-year-old in my stead, and briefly before I would tag in and do the same — and I got to thinking about Jack Crowley’s 2025/26 so far.

In a general sense, Munster’s attack has been functionally underwhelming this season, and I think that’s an objective fact. Yet I don’t think the heat for that lies with Jack Crowley, or should do, anyway. As is often the case, if an attack has issues, the primary fly-half is usually the one who takes the heat, and I think that’s broadly the case here, alongside the fluctuating whims of Andy Farrell at Ireland level.

My main critique of Crowley this season has been with his goal kicking; he’s hovering around 75-78% at the moment across the test game, Europe and the URC, with some notable misses against Gloucester and Leinster, in particular, along with a few missed kicks to touch that have been costly in the moment.

There’s no two ways about — that side of his game has to find more consistency, or it’ll drag the perception and, to be fair, the reality of his performances down. If you are your team’s primary goal kicker, your kicking is a key part of your role and not a separate mini-game. One will always impact the other.

When we talk about modern 10s, you often see the conversation default to highlight-reel attributes: linebreak creation, try assists, and the ability to turn a phase into points with one touch. However, the more interesting story in this sample is what lies beneath the surface. Put Jack Crowley beside a cross-section of elite flyhalves, and you get a very clear answer: Crowley is operating as a high-work, high-efficiency connector-10 for us and that shapes both our strengths and our current limitations.

Attack, carry, breakdown

| Player | Min | TI/80 | DomC% | GL% | 2+% | Ev% | AR/80 | AR Eff% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crowley | 422 | 0.9 | 16.7 | 66.7 | 25.6 | 42.3 | 3.2 | 94.1 |

| Ntamack | 649 | 0.7 | 51.3 | 68.3 | 35.0 | 27.0 | 2.3 | 89.5 |

| Finn Russell | 464 | 0.5 | 27.8 | 43.8 | 18.8 | 58.3 | 0.9 | 80.0 |

| Fin Smith | 480 | 1.3 | 55.6 | 63.8 | 41.4 | 24.4 | 4.2 | 92.0 |

| Matthee | 416 | 0.8 | 47.8 | 78.8 | 33.3 | 58.6 | 1.9 | 90.0 |

| Jalibert | 742 | 1.6 | 49.2 | 65.0 | 31.7 | 63.0 | 1.6 | 100.0 |

| Prendergast | 378 | 1.1 | 11.1 | 59.5 | 21.6 | 35.3 | 3.6 | 82.3 |

Key: TI/80 = try involvements per 80; DomC% = dominant carry %; GL% = gainline %; 2+% = % carries vs 2+ tacklers; Ev% = evasion %; AR/80 = attacking rucks per 80.

Defence, turnovers, defensive rucks

| Player | Min | Tackle/80 | Tk% | DomT% | 1st% | Tackle above Waist% | Def Ruck/80 | Def Ruck Eff% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crowley | 422 | 11.4 | 90.9 | 2.9 | 64.7 | 50.8 | 1.1 | 0.0 | |

| Ntamack | 649 | 6.5 | 85.5 | 1.6 | 64.1 | 13.8 | 1.2 | 0.0 | |

| Finn Russell | 464 | 7.2 | 64.6 | 2.9 | 64.7 | 33.9 | 1.7 | 10.0 | |

| Fin Smith | 480 | 9.0 | 80.6 | 6.8 | 54.8 | 38.2 | 1.3 | 25.0 | |

| Matthee | 416 | 4.2 | 71.0 | 0.0 | 64.9 | 42.4 | 0.8 | 75.0 | |

| Jalibert | 742 | 5.4 | 70.4 | 8.5 | 76.8 | 20.6 | 1.1 | 20.0 | |

| Prendergast | 378 | 4.7 | 73.3 | 5.7 | 60.0 | 33.3 | 2.1 | 0.0 |

Workhorse

Crowley is the defensive workhorse of the group: 11.4 tackles/80 at 90.9% is the defensive combination nobody else touches in this sample so far this season. It isn’t just volume, either. It’s elite-level defensive accuracy that plays a significant role in Munster’s overall defensive solidity. At a base level, in phase play, transiton and setpiece, Crowley allows every other defender on the team to focus on their own lane. Even compared to rock solid defenders like Smith and Ntamack, Crowley is by far the #1 player in these metrics. The primary role of a flyhalf is always going to be on the offensive side of the ball, but that doesn’t mean that great defence is window dressing either; it’s an important part of being a complete player.

When you add in the breakdown: Crowley is also 3.2 attacking rucks/80 at 94.1% — top-three for volume, and near the very top for efficiency. Importantly, his number is down from his 5.1 attacking rucks/80 that he had last season, which I felt was something he really needed to taper back to give him more opportunities on-ball. I would say that 3.2 attacking rucks is a little too much as it stands, but it’ll take more comfort in the system and a more settled team around him to fully bring that number in line with the 2/2.5 attacking rucks per game that I think he should be living in.

Essentially, Crowley is doing a significant amount of our stability work, both in defence and in keeping our attack functioning after contact.

The Ball In Hand

This cohort of players splits into very clear archetypes when we look at their metrics in possession:

- Collision-and-engine 10s: Fin Smith and Ntamack drive value through dominant outcomes and multi-defender commits. Smith’s DomC% (55.6) and 2+% (41.4) is the purest version of that profile of the flyhalves I profiled.

- Hybrid threats: Jalibert and Matthee are the rare blend — high evasion and high dominance. Jalibert in particular is an outlier: Ev 63.0 with DomC 49.2, and the best Try Involvements/80 (1.6).

- Evasive conductor: Russell has the evasion (58.3) but the carry outcomes are weaker here (GL 43.8), and the defensive efficiency is the lowest in the sample.

Crowley sits right in the middle of this group, offering a little bit of everything:

- Evasion: 42.3 (solid, mid-table)

- Gainline: 66.7 (strong)

- Dominant carries and 2+ tacklers: 16.7 and 25.6 (lower half)

So Crowley is not lacking evasion — if anything, his evasion stats are wildly improved on last season’s 36% — but what he lacks relative to the top attacking profiles is the blend of evasion with repeated carry gravity (dominance or consistent multi-defender commits). That’s the difference between “good carry selection” and “structurally bending a defence” but I have my reasons why I think those carry dominance and gainline numbers aren’t quite where his evasion stats suggest he should be.

Try involvements

Crowley’s 0.9 try involvements/80 is a respectable number in this group. But the separation at the top is clear:

- Jalibert 1.6, Fin Smith 1.3, Prendergast 1.1.

That matters for our lens because it suggests Crowley’s output is not “absent” — it’s just not at the level of the most attack-driving profiles in this sample, and the reason is unlikely to be a single skill. It looks more like role + workload + where the attack’s gravity is coming from. Essentially, Crowley is producing opportunities, but they aren’t being converted at the same level that Bordeaux, Northampton and Leinster are as a collective as of yet.

What this means for Munster

We are currently using Crowley as a connector and stabiliser, not purely as a playmaker.

The numbers scream workload: tackles and rucks. That can be a competitive advantage — particularly in tight games where tempo and error-reduction matter. Our collective error rate per possession is quite low and Crowley’s base game plays into this quite a bit but we’re not putting him position to break teams down.

There is an opportunity cost that we should take seriously.

A #10 living at Crowley’s defensive volume is paying a tax somewhere: repeat accelerations, repeated phase-end decision-making, and the ability to take three or four attacking “touches” in a set without drop-off. Essentially, is that defensive workload taking something from him on the offensive side of the ball?

If we want more attacking ceiling, the lever is not “more evasion” — it’s more gravity.

The best attacking profiles here either:

- win collisions and force defensive over-commit (Smith/Ntamack), or

- combine evasion with dominance (Jalibert/Matthee).

Crowley’s evasion is fine. The growth area is carry outcomes that change defensive behaviour — dominance and/or 2+ tackler attraction — because that is what creates the next phase’s space for us. That, for me, is all about giving him more dominant carries to slingshot around. Rather than being the guy who draws defenders, he needs to be guy who is swerving into the space opened up by others.

Practically: protect the 10’s battery.

If we want Crowley to climb towards the top end of try involvement without changing who he is, the simplest structural idea is to shift some of the hidden work away from him — particularly defensive load and post-contact duties — so his best touches happen more often, further away from the “engine room” and later into games.

***

Jack Crowley’s big strength as a playmaker is his ability to play really flat to the screen, and use his pace and power to draw defenders into his lane, where he can either attack directly or pull another defender out of position.

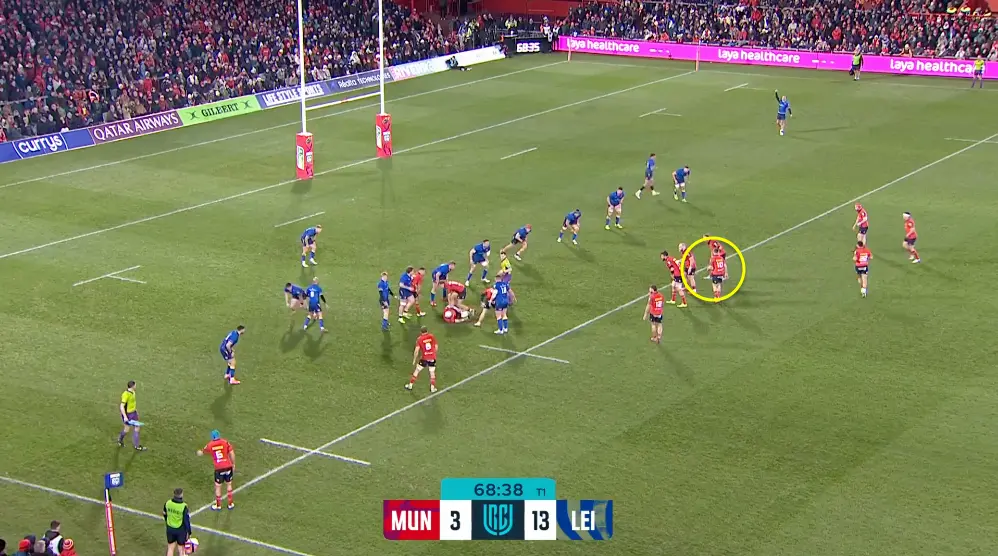

You can see that here against Leinster, in particular. Look at how many late decisions he makes on the gainline.

He’s really good in these spaces, and his athleticism allows him to start inside the pod, sprint into the space where the screen pass goes and attack around the corner into floating defenders. When our attack works really well, Crowley usually looks like the standout player on the pitch.

The problem is; that system doesn’t work often enough.

Why not?

The main problem is this; we are a contact-first, short-passing team that does not win enough collisions.

From OPTA stats post-Ulster game for 2025/26 so far:

- Dominant carry %: 27.9 (low, and directly relates to the 2+ tackler numbers)

- Gainline %: 55.0 (middling)

- 2+ tacklers %: 47.7 (high)

- Evasion %: 16.8 (low)

- Offload success: 83.3% (excellent)

- Offloads leading to try/break: 8.3% (low)

- Touches per error: 30.1 (reasonable)

This is a very specific combination:

- We are getting held up in contact (high 2+ tacklers) without consistently turning that into dominance.

- We do offload accurately, but those offloads are mostly “survival/continuation” rather than structural damage (low % leading to breaks/tries).

- Low evasion at team level suggests we are not routinely winning on footwork; we are trying to win by shape, tempo, and repeat phases.

Our movement profile reinforces “flat, close-to-contact”, repeat.

Looking at our team shape

- % <10m: 56.6 (high → lots of short connections)

- % wider than 1st receiver: 26.1 (not especially high)

- Blind %: 14.5 (notably high)

- % 20m+: 8.0 (modest)

- Possessions ended by kick: 40.2 (significant)

- Contested kick %: 14.3 (modest)

- Rucks <3 seconds: 5 (in the same narrow band as others shown)

In the flat 1-3-3-1 shape we usually play, this reads to me like:

- We are often playing off the near-side pod(s) and short, with a meaningful amount of blindside use which we try to activate by a higher volume of short tip-on or inside ball, or screen ball played in close quarters.

- We are not consistently stretching teams “beyond first receiver” often enough to make our high-contact approach pay.

Where Crowley fits

Crowley’s individual profile:

- Attacking rucks/80: 3.2 (94.1%) → high involvement, elite efficiency

- Tackles/80: 11.4 at 90.9% → huge defensive burden, elite accuracy

- Evasion: 42.3 → mid-to-high in that #10 cohort

- Dominant carry %: 16.7 → low

In a flat 1-3-3-1, the 10 is often asked to live “in the engine room”:

- connect front-door carries,

- be present for the next job (clean or reload),

- and make defensive reads on repeat.

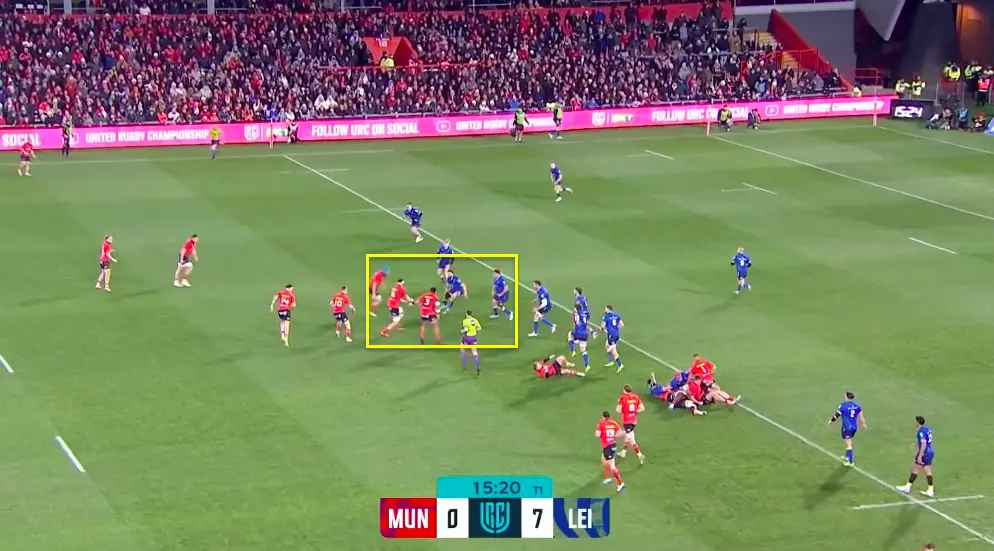

Look at how flat Crowley is to this three pod.

Crowley’s numbers scream that we are using him as a connector and stabiliser first, and he is delivering that at a very high efficiency level.

This also explains why he can look like he’s “everywhere” but still not always “decisive” in highlights: he’s doing a lot of the work that keeps the whole system standing up.

Where the fit becomes limiting

The single biggest mismatch is this:

- Munster team evasion: 16.8

- Crowley evasion: 42.3

That gap is actually very meaningful.

It suggests Crowley has more “beat-you” capacity than our team attack is currently extracting, because our default behaviours (short, flat, contact-heavy, high 2+ tacklers, low dominance) reduce the number of moments where a 10’s footwork is the primary weapon to get him clean separation. On a tight screen like this, we need that three pod standing more defenders up.

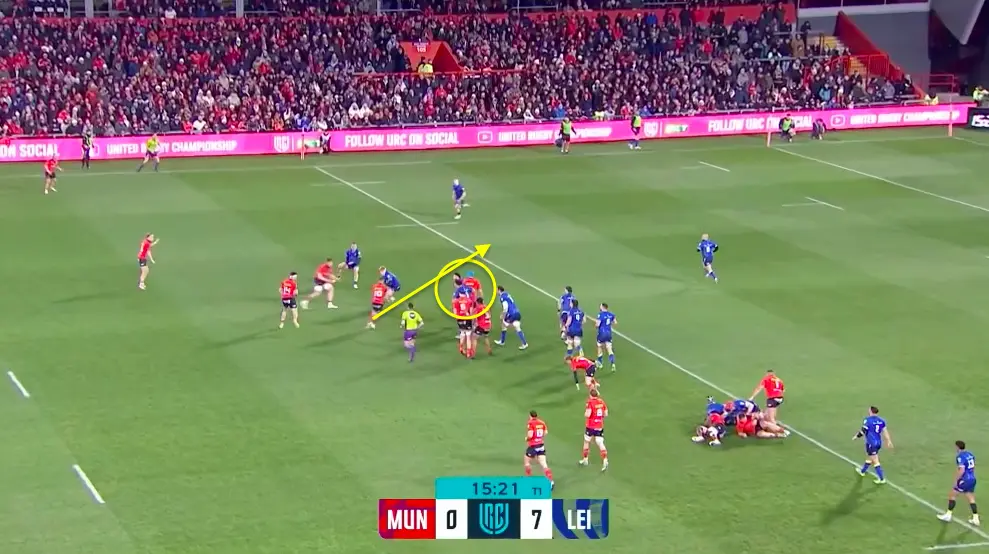

So that it empowers a cleaner gap on the screen here;

If we’re honest about the team numbers, we are often creating phases where:

- the defence is set,

- the ball is delivered flat into traffic,

- and the job becomes win contact/struggle against breakdown pressure/recycle/repeat.

That environment rewards a “worker-10” profile (which Crowley is giving us), but it does not maximise his evasion unless we deliberately build it into the pattern.

What this implies about our 1-3-3-1 shape

If we keep the flat 1-3-3-1 as our base shape, the cleanest way to square the circle is role clarity:

The pod carriers must supply the collision value Crowley does not

Crowley’s low dominant carry % isn’t necessarily a flaw in his game — you don’t need a crash ball #10 – it’s a usage signal that we’re not winning enough collisions.

If our pods are not delivering dominance, we get exactly what the team numbers show:

- lots of 2+ tacklers,

- modest gainline,

- and offloads that don’t turn into breaks.

So the “fix” ensuring our 3-3 middle shapeconsistently create either:

- dominance, or

- rapid ball with a fractured line.

Crowley should be the second-touch threat, not the first collision

In a flat system, the easiest way to unlock a 10’s evasion is to make him the second decision-maker but the issue is, we’re already doing that.

Think about what you’d look for your #10 to do if they were really good at slipping tackles but you weren’t winning collisions. You’d have your #10;

- carry option behind the tip (which we do quite a bit)

- pull-back to him after a short carry (which we do quite a bit)

- or a pre-called “out-the-back” where he receives against a moving, reorganising defence (wh

So if we’re already doing that, what needs to change? Well, barring the simple fix — just win more collisions — we have to nail down what we’re doing in the pod shapes.

Tip-on punishment: make the pod’s first action dent

You do not need every pod carry to be dominant — but you need enough dominant outcomes early that teams can’t send extra bodies behind the pod with impunity.

What changes that fastest:

- One carrier who consistently wins the first collision (or consistently gets an arm free through contact). That means loading up Coombes, Gleeson and Edogbo — all playing at the same time — for constant carrying in middle line positions.

- Tighter carry selection: less “carry to have a carry”, more “carry into the seam” (shoulder of the guard/inside defender) where dominance is most likely.

Out-the-back punishment: if they swarm behind, we need to hit where they vacate

If defenders are stacking behind the pod, they’re leaving something undermanned:

- the inside guard space,

- the short edge,

- or the reload to the same side (because bodies have been committed to the “behind” space).

So the answer is not abandoning the out-the-back; it’s pairing it with a repeatable “if they sit, we go through” decision making late in the carry:

- A pre-called “trap” where the pod shows out-the-back but the ball goes hard tip / hard unders line into the space those hunters have vacated.

- A second-phase return ball that targets the same seam on the first carry before the defence can re-fold.

This is also where Crowley’s profile is important: his attacking ruck load suggests he’s often in the clean-up lane rather than being the strike receiver on the immediate next touch. If we want to punish blitzing defenders in our screens, Crowley has to be available for the next decision, not buried in the previous phase’s recycle.

Tactical punishment: if they’re hunting behind the pod, the kick has to hurt them

The most reliable way to stop defenders “living” behind the pod is to make that positioning vulnerable to a kick.

Not a random kick — specifically:

- kick in behind the hunters (who’ve stepped up/off the line to kill out-the-back). In practice, this would mean Crowley leaving a little more space on certain screens to knock a chip over the pod that just passed to him.

- or kick to the space they’ve left on the edge space when they over-allocate behind the pod and the defensive line compresses in to compensate.

Right now, our kicking indicators are:

- Possessions ended by kick: 40.2% (so we kick plenty)

- Contested kick %: 14.3% (modest)

That suggests we kick, but we’re not always using it as a shape-enforcer — the kind of kick that changes how defences are allowed to fold and hunt our looping backs. If the defence can hunt behind the pod and be comfortable that we won’t punish them with ball-in-behind, they’ll keep doing it all day.

Our offload quality needs a next-phase plan

We already have 83.3% offload success. The problem is that only 8.3% of those lead to try/break.

That is basically telling us that we complete offloads really well, but we’re not striking on the next action.

Crowley’s ruck involvement suggests he is often part of the “secure it” response rather than the “kill shot” response. So we’re offloading to survive, not offloading to puncture — and that keeps dragging our 10 into the clean-up role. Not as much as last season, but enough to be meaningful.

Crowley’s data fits our current Munster identity: he’s the glue in a flat, contact-heavy 1-3-3-1. The issue is that our team-level outputs — low dominance, low evasion, and offloads that don’t become breaks — keep pulling him into the “maintenance” role. If we want more attacking ceiling without abandoning our shape, the answer is not asking Crowley to win collisions off the screen, or having him pop the ball to another forward who doesn’t win the collision before getting counter-rucked, it’s making the pods win those moments, and designing the second touch so Crowley can actually use the evasion he’s clearly worked on.